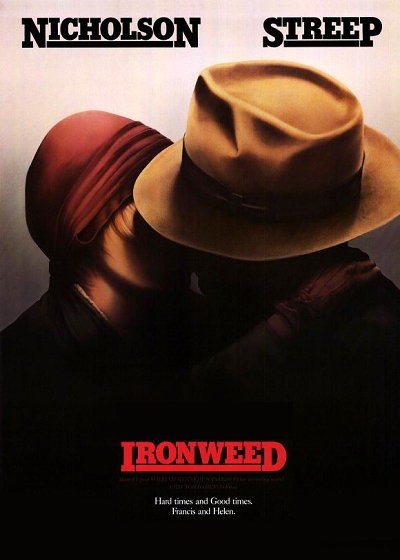

Ironweed

December 18, 1987

· Vestron Pictures

· 143 minutes

|

Ironweed may not hold together like clockwork, but the raw stuff of it is often beautiful and terrifying. Start with the absolute defiance inherent in the subject matter: Kennedy’s novel is set in 1938 Albany, amid the demimonde of deep-Depression vagrancy, where the bums and skidrow losers have only wild-animal decisions to make, about where to find food and hootch, what backbreaking dayjob they can scrounge, what alley to sleep in, how to stay warm in the winter nights so they don’t simply freeze to death, at which point “the dogs will come along…” Imagine if you can an American movie now being made in this territory, even from a prize-winning novel – it’s remarkable not only for the daring of its gloom, but for its fidelity to its unusual period and place, which is not anywhere we’d hanker to visit in our lust for escapism. (Depression-era movies, since the ‘60s, have tended toward the warm and dusty South.) Babenco and his DP Lauro Escorel capture the inhospitable small city in unforgettable grainy tones, and the sense of being lost in a quiet, dark town at night, with its storefronts lit up and distant sounds portending possible hazards, is indelible and unique. The sojourn into the lower depths is handled with a gentle simplicity – no howling pedagogy or menacing drama cues – and Babenco fuses for the first time squalid American poverty with magical realist poignancy, beginning his film with a dream-image of a locomotive billowing steam and then transitioning upwards through cotton clouds to blue sky, and then back down, finally, to the windy, trash-strewn lot where Francis Phelan (Jack Nicholson) awakens under cardboard after a particularly bad night. Taste this bit of dialogue, between Phelan and fellow loser Rudy (Tom Waits), as they chase hungry dogs away from the prone figure of a passed-out Indian woman, and try to get her to shelter as night descends again: “She’s been a bum all her life.” “…She had to do something before she was a bum.” “Well, she was a whore, in Alaska.” “What about before that?” “I don’t know… I guess before that she was just a little kid…” “Well, that’s something. Being a little kid is something…”

It was very cold. Just f–cking cold. You cannot imainge how cold. And I had a little cloth coat. I had a profound understanding of what it was like to spend the night outdoors, because we shot all night in Albany in February. I’d come home to Connecticut at four or five in the morning. I have a very light-filled house. So I would sleep in the closet, because it was the only place that was dark and (laughs) where the kids couldn’t find me. (Meryl Streep, Entertainment Weekly, March 2000)

Kennedy’s book is rich in this kind of titanic melancholy, and the film channels it with textures: darkling set design, John Morris’s bruisingly sad lullaby score, and acting. Nicholson, already in the lazy, showboating, I’m-just-Jack phase of his career, clearly relished the role’s grim implications: Phelan left his family 15 years earlier after accidentally dropping and killing his newborn son. Nicholson doesn’t overplay the grief and guilt; Phelan is a man used to the streets and tired of life, but Nicholson gives him a restless edge, as if he’s always looking just beyond every scene, toward another, truer way to escape, or keeping an eye out for the ghosts for whom he’s responsible. The action of the film is in some ways kickstarted by a day spent digging graves for pocket money; Phelan ends up in his dead boy’s cemetery, and the scene where the slow, stooped man confronts the grave might be among the top five swatches of Nicholson’s redoubtable career. But of course he’s overshadowed by Meryl Streep, as a sickly, ex-radio chanteuse who drifts in Phelan’s shadow (when she isn’t letting other bums fondle her for a night’s sleep in an abandoned car), and half-lives in a fantasy world of affluence and lingering fame. Muttering her lines in a deep, confused voice, her bloodshot eyes unsteady in their tiny sockets, Streep makes it perfectly clear without saying so that her Helen is both chronically ill and borderline psychotic. One of the film’s pivotal scenes cements the deal: when in a grungy gin mill Helen is cajoled into singing “He’s My Pal” for the paltry crowd, her performance subtly rips with rousing confidence, and the light grows more golden, and the bar patrons respond with happy applause, and then Babenco cuts to the reality: Streep’s withered old girl rasping out the song’s last bars obliviously (the sunny version was not her hallucination, but her dream), to no applause at all. There’s the lie of the American Dream, distilled in a single cut to a middle-aged woman’s delirious and hapless open mouth. The tragedy of Ironweed is not an easy morality tale, but an explanation of America (in poet Robert Pinsky’s words) in its saddest, least humane moment. Babenco, a Brazilian who came to Hollywood on the strength of Pixote (1981) and got himself Oscar-nominated for Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985), deserves more credit for the resonant details of the movie (for instance, the closeup of the unexplained family photo on Helen’s flophouse nightstand the day she dies), and for the sugar-coated Hollywoodization that he didn’t allow to take hold, than for the clumsy spiritual manifestations, or the occasional over-punctuated supporting bit (Michael O’Keefe and Diane Venora spitting bitterness at each other as Phelan’s grown children, upon his return home). It’s not a perfect film, but what’s perfect? Under the cosmetic arguments there is a plaintively beating heart.

“Ironweed” is one of Meryl’s lesser known films – or lesser mentioned ones. The most memorable scene might be Meryl’s rendition of “He’s me Pal”, but the film features a bunch of wonderful scenes with her and Jack Nicholson. This is acting at its best, in a film that I found lenghty at times. We follow two drifters on the streets of Alabama for a couple of days. Francis has lost his family, and his mind. Helen is his companion for years, although we don’t learn as much about her past than we learn about Francis’. Streep’s character reminded me of the nun in “Doubt”. Helen Archer wears her scruffy hat like a habit – at times you don’t even see her face. All you hear is her voice and her pain. This is a woman who has died inside already and is awaiting her death, there isn’t much more to expect of life. And it’s only until the last scene in the hotel room, when Helen takes off her hat, that you see the actual person for the first time. It’s a prime example for Meryl’s ability to transformation, once again, that even when all the costume and makeup comes off, and the character looks into the mirror, you still cannot Meryl Streep. It’s like she has given her character different eyes. She has a couple of heartbreaking scenes, especially the one in the church and, after meeting an old friend, shouting at strangers on the street. Unfortunately, her character vanishes from the film halfway through. The focus on Nicholson’s character and backstory I found rather lenghty and not as powerful as his scenes with Streep. Still, you can’t blame the film for not having enough pace – for a story about two alcoholics living into their day, “Ironweed” does the best it can. The directing by Hector Babenco is exceptional and you’ll see some familiar faces throughout the film, including Tom Waits and Meryl’s longtime colleague Joe Grifasi. I’m sure most critics dismissed the film simply because Streep and Nicholson didn’t choose a star vehicle to work together, much like they didn’t do in “Heartburn”. The film was overlooked by awards juries as well, with the exception of the Academy Awards, who honored Meryl and Jack with acting nominations. I’d recommend “Ironweed” to those who enjoy outstanding acting and don’t mind a film to be slower at times.

☆ Academy Award – Best Actress in a Leading Role