|

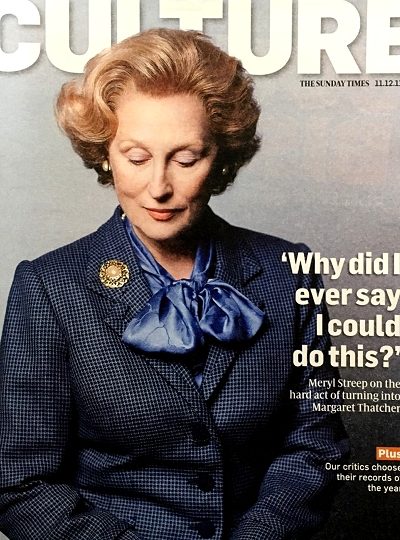

The Iron Will of Film's First Lady

The Sunday Times ·

December 11, 2011

· Written by Nev Pierce

|

Meryl Streep first saw Margaret Thatcher in the flesh a decade ago. The two-time Oscar-winner was taking her eldest daughter to university at Northwestern, in Evanston, Illinois – “Unloading the car, putting up the curtains and stuff” – and saw a poster advertising an on-campus speech from the former British prime minister. “I said, Mamie, come on, let’s go!” she says with freshly remembered glee. The pair scored last-minute seats and watched the lecture. “Then the university president said Mrs Thatcher would take questions for one half-hour precisely. She carried on for an hour and a half – she never tired. She sort of gained, if anything, interest in going on. Speaking in really cogent, beautifully wrought paragraphs. Very, very impressive. Even though the politics were not anything we agree dwith, she was impressive. Just that galvanising intelligence – making her point, never losing track of the question, always circling around to the point that she wanted to make.” This is not unlike Streep herself. She’s in London briefly, having come in “on the red-eye” for a blink-and-miss-it visit. She’s tired, no doubt: her eyes squint occasionally through narrow glasses, but flare with enthusiasm when she warms to a subject. Spangly necklace over lightly patterned top, black trousers over neat boots, she’s a picture of polite, unpretentious good taste. It’s reflected in her tripple: prior to the interview, a publicist tried room service, seeking some PG tips for her. (She had to settle for the fancier brew available in this upmarket Soho hotel.) Press is not something any actor really, deep down, appears to enjoy, but Streep shows curiosity and a generous laugh, and is as expert an interviewee as you’d expect after years of pushing her pictures in a career characterised by determination, energy and longevity.

She received her first Oscar nomination 33 years ago, for The Deer Hunter. On January 23, she will without doubt snare her 17th, for The Iron Lady. Then, on February 26, she has a strong chance of taking home her third Oscar. (She previously won best supporting actress for Kramer vs. Kramer, and the big one for Sophie’s Choice.) The New York Critics Cirlce best actress award for 2011 is already hers, for The Iron Lady – it will be the first of many. Thatcher’s official biographer, Charles Moore, has already written of her performance that it is “uncannily brilliant”, and manages to get Mrs Thatcher without ever succumbing to mere mimicry. Streep, he says, “captures virtually every mannerism and trick of speech: a light movement of the lower lip after speaking, the smile that can suddenly frost over, the mixture of very genuine courtesy to people in general and shattering rudeness to senior colleagues”. The only thing, in his view, she doesn’t get right is the walk – not enough of a scuttle. Streep already has every accolade an actress could hope for, but this astonishing performance suggests that, at 62, she has no intention of slowing down. “I do have a lot of energy,” she confirms, “but I have nothing compared to this woman.” Nowaways, Thatcher’s initial achievement is perhaps underestimated in an age when she has become an icon, a figure who attracts both love and revulsion, rather than a person. But the film ably captures her attempts – first as Margaret Roberts, then as Mrs Thatcher – to achieve election to parliament and to establish herself there. (The British actress Alexandra Roach plays the young Thatcher superbly.)

“It was a men’s club” is Streep’s matter-of-fact assessment of the Commons. “There were women there, but I think it was 16 or 17 out of 630. I went to a men’s college back in the 1970s – I was one of 60 women, and there were 6,000 men on this campus. This was Dartmouth – in the days of Animal House…” She pauses to check that the reference to National Lampoon’s raucous college comedy has crossed Atlantic with her. “That was it. We were the first, the canaries in the mines, while these schools in the United States were deciding whether to go co-ed or not. It was a really interesting time. The world was changing. You could feel the old order breaking down. There were many people who really didn’t want it to change, really didn’t want us there. You could feel it. White-hot rage that didn’t speak – just emanated. I’m sure she experienced that. I’m sure she experienced it.” Class was another element of fight, Streep says: “It’s hard to quantify which prejudice kept her out of the inner circle more. But for her to achieve that at that time was incredible. Incredible. And to stay there. And stay there. To be the longest-serving prime minister of the 20th century. Amazing”. Staying power is not something Streep lacks, of course – so much so that she is perhaps at times taken for granted. There has been a certain relentlessness to her brilliance, which it is easy to resent. And for years, whether they were arrived at through her taste or were what was on offer, the thought of watching her films felt a little like doing homwork. You just assumed they would be about something challenging and difficult: the Holocaust (Sophie’s Choice), the trauma of losing a child (A Cry in the Dark) or terminal disease (One True Thing.) She has tried to mix it up before – perhaps most egresgiously in 1992’s surgery “comedy”, Death Becomes Her – but it is the past decade that has seen Streep really succeed in confounding expectations. She was hilarious in the postmodern screenwriting comedy Adaptation, both playful and sexy as a writer bewildered by her infatuation with an orchid thief. Then the Abba musical Mamma Mia! proved the biggest surprise – and commercial success – of her career, waltzing away with $610m (£389m) at the worldwide box office. It showed a broad audience and unimagined lighter side to Streep, which was exploited again in the charming divorce romcom It’s Complicated. She has shown what many have long suspected: that there is a cinema audience out there beyond 16-year-old boys who want to see things blow up. “It’s the financiers,” she says. “Narrowing, narrowing who they aim at. It just has to be a (video) game. It it can morph into a game, we can really make our money! That’s where it has devolved to.” She sounds weary, as if they really, really should know better, before pointing to the future. “But with the atomisation of the business and how people assume these things will be delivered, immediately, on demand (through the internet and television), then they’ll find out there’s an audience lying in wait, parched, that hasn’t been served what it wants for years and years.”

The unvervaluing of women, whether in the audience or on the screen, has become a long-standing complaint against Hollywood. It has changed a bit in the past few decaded, Streep feels, with more female studio executives being appointed. “But they’re essentially playing football. They have to learn how to play football. It’s not necessarily that they’re playing a woman’s game. That’s what’s so cool about this project. It was generated by Phyllida [Lloyd, the director] and Abi [Morgan, the screenwriter], edited by Justine [Wright]. We all collaborated. It was really an unusual thing. Oh and Cameron McCracken [managing director of the film’s distributor Pathé]. An honorary girl! I can say that. He’ll like that.” She giggles, then returns to her point. “But this was extremly unusual. It’s rare that those voices dominate. I don’t know why, but it is.” Streep became involved in the project early, after Pathé had had a meeting with her Mamma Mia! director, Lloyd. “Someone suggested Meryl, and I went a bit blank,” Lloyd says on the phone. “It was like a clash of the titans in my head. I felt taking on a piece about Margaret Thatcher was one thing to get my head around. The second was whether bringing in an outsider to play her was the right thing to do. Then I realised that you need a superstar to play Thatcher. And, as we began to shoot, the thing that struck me, why, if it works, it really works, is that Meryl is an outsider, just Thatcher was. And Thatcher had to work hard to overcome. To the cabinet she inherited from Ted Heath, she was a nightmare from which they thought they would wake up. She had to work so hard to become leader – she had to change her voice and change her hair and her whole presentation of herself. She had to evolve. I think, in that way, Margaret Thatcher had to work as hard as Meryl did to become that person.”

For Streep, the transformation involved her usual process of intense preparation – and outright panic. “I’m all over the place,” she says, flapping her hands. “Calling my husband [the artist Don Gummer], saying, Why did I ever say I could do this? I can’t do this! And he says, “You always say that. Alyways. I say, I do not, this is the first time. I just have to immerse myself in the messy way I do it. It’s a sort of focused chaos, is how I’d put my process. She listened preatedly to recording of Thatcher, “Listening, listening, listening – rather than watching. I don’t hear anything that isn’t her.” And she read everything she could: the three-volume diaries of Thatcher’s confidant Woodrow Wyatt and biographies by Hugo Young and John Campbell (two hernia-inducing volumes). But then it comes down to rehearsal, to the set, to the moment. “In the end, you just have to throw all the words away,” she says. “Just live and live. Walk up the stairs and walk down the stairs. The time that I know I have it is when I know I’ve surprised them with something. Whether it was true or not, Jim gave me that, Jim Broadbent.”

She is pleased at the memory. Broadbent plays Denis Thatcher, and it is on the relationship between the two of them that the film pivots. Baroness Thatcher is in her London home, considering clearing out the cupboards of her late husband’s things (he died in 2003), when he appeara to her in a hallucination, triggering a journey into her memories of youth, ambition and the quest for power. While some people will inevitably view (and review) the film through their own political prism, what is remarkable is how any political agenda disappears, making it really about the point of view of one woman wondering if she made a difference – and desperately missing the man she loved. And Streep is extraordinary, slipping in and out of memory and the moment, showing Thatcher’s sharp wit and her sadness as the years blunt it. It is a performance that transfixes you, in the strict, dictionary definition (“To make or hold motionless with amazement, awe, terror”).

It was a role that Streep found difficult to shake off. “With something like It’s Complicated, I really left it at the set,” she says. “But this I carried with me more, because it was more personal.” She sits forward on the sofar, stretches up, runs her fingers through her hair – shaking out the tiredness of the memories. “Just standing that way for a long time was wearing. And the banked energy of playing someone whose energy had ebbed, it had an effect. It did have an effect. It reminded me so much of my mother and my grandmother. It’s emotional to go into these places.” It’s emotional to watch them, too. The most significent achievement of The Iron Lady is that it gets you past the politics to see the person – the tension between power and the personal, between calling and family. It’s something Streep, like many of us, is familiar with. “Everybody has their things with their children, and each child is different,” she says, reflecting on her four children (from a marriage now in its 34th year). “Even though you have the same rules for everybody, everybody takes it a different way. Stuff happens. Things come up. Life is much layered and challenging.” This is true even if you are the most powerful woman in the country – or the best actress in the world. Streep concluded: “What I loved about the way Abi constructed this is that it starts as being about Margaret Thatcher – but it ends up being about you.”

The Iron Lady is released on January 6.

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|

Posted on November 7th, 2024

|

Posted on November 1st, 2024

|

Posted on October 10th, 2024

|

Posted on September 26th, 2024

|