|

Simply Streep is your premiere source on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her the praise to be one of the world's greatest working actresses. Created in 1999, we have built an extensive collection to discover Miss Streep's body of work through articles, photos and videos. Enjoy your stay.

|

|

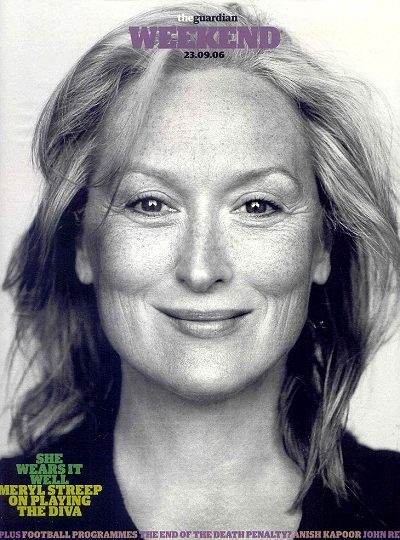

The Devil in Ms. Streep

The Guardian ·

September 23, 2006

· Written by Emma Brockes

|

The Devil Wears Prada is a film about status and here we are in Venice at a time of year – the film festival – when the Hollywood feudal system lays itself bare. Those in attendance wear passes and wristbands and all the other formal indicators of caste, but as a general rule of thumb, on this late summer morning, you can tell how important a person is by how much they are sweating. Down a long hotel corridor the entourage comes: first the damp-fringed PR serfs, then security men baked in black suits; a phalanx of gently perspiring personal assistants forms the inner circle and, in the middle, like an atom borne along by the activity around it, is Meryl Streep, in cornflower blue. Ms Streep is not sweating. She is smiling, as the highly visible are obliged to do, and which she will later inform me – “My God!” – takes some energy; “to be nice all the time”. As she enters the publicity suite, an attendant points out in a low (but not quite low enough) voice that the toilet at Ms Streep’s disposal is distinct from the one that will be used by those who are not Meryl Streep.

She is one of the most famous actresses in the world, but it is strangely hard to pin an image on Streep. Over the course of her career she has laboured to establish herself as an actor whose roots lie in ordinary life. She admits to not washing her hair very often (her record is three weeks); she drives a modest, ecologically sound Toyota Prius; she lived until recently in Connecticut with her husband Don Gummer, a sculptor, and their four children – they are back in New York now – and when she speaks, she generally has something to say. Paradoxically, this contrives to make her seem even more regal. At 57, Streep is beautiful in an unfussy way; she gesticulates and clutches handfuls of hair and moans theatrically that Venice is a chore, although she hears that “Jeremy may be in town next week”. Oh yes, Jeremy Irons, her co-star in The French Lieutenant’s Woman. She smiles beneficently. She is still an actor, after all. For her 33rd movie Streep has chosen to play a modish role, that of Miranda Priestly, the villain of Lauren Weisberger’s hit novel of 2003, now adapted for screen and co-starring Anne Hathaway. Weisberger wrote the book after spending a year as assistant to Anna Wintour, editor of American Vogue, whom she lightly fictionalised as a woman of such joyless vacuity that she could depressurise a room just by entering it. It is an interesting role for Streep, who has herself from time to time been labelled an “ice queen” and who one imagines hesitated to accept a part so nakedly based on a living person. Ethically, Weisberger was thought to have done something rather dubious with this book, which was singled out by literary New York for an unusually severe kicking.

Streep loftily removes herself from all this. There was no awkwardness, she says, when she met Wintour for the first time at the film’s gala premiere in New York. “We chatted, briefly. She was very gracious. I think the book was probably more upsetting to her than the film.” Her intention, she says, was to depict neither Wintour nor Weisberger’s idea of her but to come up with her own characterisation, thank you very much, and the Priestly of the film has been duly Streepified: beefed into the third dimension with a sense of humour, an appreciation for the macro-economics of fashion and, in one memorable scene near the end, a dash of devastated vulnerability. It’s fascinating to watch Streep train her heavy artillery on such slight material; stripped of make-up and looking like a mollusc prised from its shell, she plays the breakdown scene so hard that her eyes seem to turn from blue to black. (Trying to bump up sympathy for the old dragon, I suggest. But Streep snaps, “I didn’t give a damn about sympathetic. I cared about true.”) She calls The Devil Wears Prada a “serious/frivolous movie”, that is “a lark, fun to watch, but its architecture – its bones – are sharp”. Given that the last book Streep enjoyed was by Orhan Pamuk, you wonder if she isn’t snobbish about the film’s chick-lit origins, just as you wondered, in 1996, if she was sniffy about appearing in the adaptation of Robert James Waller’s much mocked tear-jerker The Bridges Of Madison County. (Which, thanks to Streep and Clint Eastwood, was actually very good.) She says: “It’s always very telling what’s popular. There’s a reason that Bridges was popular and there’s a hidden power in Prada. I wanted to locate what that was.” This was partly its revenge-on-the-boss fantasy and partly “something deep about powerful women and how terrifying they are. And how much of a problem we have with that.” It doesn’t quite fly, this attempt to pass off Prada as a defence of powerful women, since Streep’s character deserves everything she gets. One may be discriminated against, I suggest, and still vile in one’s own right.

“Yes. Exactly. Yes! Yes. But … in my own experience of male and female directors, people have a much, much harder time taking a direct command from a woman. It’s somehow very difficult for people. You can’t excuse Miranda’s behaviour, but there is a certain directness that is necessary as the boss. The truth is that this is an incredibly high-pressured position; the buck stops with her. If somebody has to get her a cappuccino because she can’t run down and stand in line in Starbucks, then suck it up and go get it for her. If she works till 2am to go through the magazine, somebody has to deliver the dry-cleaning. Boo hoo, what a horrible job.” Pause. “I felt, if not sympathy, then understanding of that.” Mind you, she says, she wouldn’t like to be her. “I mean, to me? To me? I could not live that way. I could never, ever do that. Who wants it? Who wants to be president?” There is a knock on the door and an assistant brings cappuccino. “Lovely, darling, thank you,” Streep says and smiles extravagantly.

If you grew up in the 1970s or 80s then you were probably, at some stage, dragged to the cinema by your parents to watch one of Meryl Streep’s Oscar-winning performances. You may have sat there in 1985 and wondered if Out Of Africa would ever end; or buried your head in your polo-neck during the sex scene in The French Lieutenant’s Woman; or wished, in 1988, that the dingo (in A Cry In The Dark) had taken the goddamn parents, too. At her best Streep makes films suitable only for adults, which outside of the porn industry is quite rare these days. (Her own children were ignorant of large parts of her career until they were in their teens, and it wasn’t until 1994, when she did a cameo in The Simpsons, that they thought she was any cop.) She gets irritated by people trying to impose a unifying theme on her work – “It’s such a crapshoot” – but has said if there is a common thread, it’s her attraction to characters she feels a need to defend. Lindy Chamberlain (A Cry In The Dark), Karen Silkwood (Silkwood), Joanna Kramer (Kramer Vs. Kramer) and Karen Blixen (Out Of Africa) are “difficult” women at odds with the times they live in. Her most famous scene is probably from Alan J Pakula’s Sophie’s Choice (1982), in which an SS guard at Auschwitz makes Streep’s character choose which of her two children to hand over for execution. It’s classic Streep, the kind of scene that makes your scalp tighten, but defter in a way is her handling of smaller, harder-to-grasp emotions. She does embarrassment very well. In that same film, Sophie is humiliated by the librarian at a New York public library for mispronouncing Emily Dickinson. Streep manages to inject just the right level of mortified colour into her cheeks before collapsing in a dead faint.

Her approach has been called too academic but really, she says, she can be quite lazy. “Sometimes under-preparation is very good, because it instils fear and fear is galvanising. It makes you break out of yourself. If you’re prepared, then you think you’re ready, and if you think you’re ready, then you’re not ready.” She grew up in New Jersey, her mother a commercial artist, her father head of a personnel department at Merck & Co, the pharmaceutical company. “He was very academic and very bright.” Her mother liked to read murder mysteries and was thrilled and amazed by her daughter’s success. As a girl, Streep read the New Yorker. “I never read big novels until I was a grown-up.” She says: “You wanna know what my mother was like? Look at Ladies In Lavender. I almost couldn’t watch it, because Judi Dench looked exactly like my mother.” (This mightn’t thrill Dame Judi, 14 years Streep’s senior. Anyway, Streep says, “I may be her biggest fan.”) She studied drama, first at Vassar, then at Yale, where she worried herself into the beginnings of an ulcer. Streep is a big worrier. After graduating she worked in the theatre, then in 1978 won a small role in The Deer Hunter, which she did enough with to get her first Oscar nomination. Streep was 29 when she was cast in the role of Joanna, the unhappy wife in Robert Benton’s anatomy of a divorce, Kramer Vs. Kramer. She doesn’t play it screamy when she abandons Hoffman and their son in the opening scene, but just overtightens the belt of her coat until the tension is unbearable.

Streep is one of the few actresses who, blow for blow, can match the heaviest of the male heavyweights without recourse to sex appeal; when you see her playing opposite Eastwood, De Niro, Redford or Hoffman it’s like watching a live-action version of that game, shark v bear; get in there, Meryl, you think, that’s the spirit. Hoffman admitted to wanting to throttle her during the making of Kramer and cattily said that 99% of what she did wasn’t acting. Does she know what he meant by that? “I know what he thinks was true.” She pulls a face. “Because he’s – I don’t know. I’m presuming to get into his brain, which is a… complicated place. I felt that he was talking about my emotional state and that I was very emotional, so he felt that I couldn’t help but give this performance.” Streep’s boyfriend, John Cazale, with whom she’d starred in The Deer Hunter, had recently died. “He also said acting with me was like playing tennis with the greats.” What a blokey thing to say. “Absolutely,” she says. “I didn’t know we were in a competition.” I somehow doubt this. At one point in the making of Kramer, Robert Benton asked his two stars what they thought Streep’s character should say under cross-examination. “And Dustin said, ‘I know what she’d say!’ And Robert said, ‘Wait. Let Meryl talk.’ And so we all went to our rooms and wrote what we thought I should say in the courtroom and the director picked mine.” She cackles. “Anyway, I thought that was the way people made films. And later on I realised, no. They want you to shut the fuck up. The talent. Put the clothes on and say what you’re supposed to say.”

Of all the accents Streep has done, she found the Australian one for A Cry In The Dark, the Lindy Chamberlain biopic, the hardest. “I had to study a little bit for Australian because it’s not dissimilar [from American], so it’s like coming from Italian to Spanish. You get a little mixed up.” She nicked her accent for Out Of Africa from Jeremy Irons’s Danish nanny. Seriously. “I thought, I’d better get a Danish accent, so I called up Jeremy Irons, coz I knew he had a Danish nanny and he made her read poetry into a tape, which I listened to on the way to Africa. The depths of my preparation were not that great.” She nearly lost out on the role because the director, Sydney Pollack, thought she wasn’t sexy enough (“For that well-known sexpot Isak Dinesen [Karen Blixen],” she says drily). Streep has never been happy with the way she looks and the accusations of coldness may partly be a function of her pointy bone structure. She remembers her early adolescence when “the baby-fat goes away and you start to see this big nose emerge and these bones in your face which were never there and you think you’re horrible looking. I was a girl with two brothers, so my brothers did not go through this. Now I’ve had three daughters, I see that every girl goes through this, where they try to put together their look. At 12 or 13 they get really worried about it and they’re in front of the mirror all the time. And you think, do I have the most superficial children in the world? But humans do this. Get consumed by it.”

The longest Meryl Streep has gone without an Oscar nomination is five years, between Postcards From The Edge (1991) and The Bridges Of Madison County (1996). She begged William Styron, who wrote the novel Sophie’s Choice, to write another part like that for her, but none was forthcoming and in the late 1980s and early 1990s she made what are considered to be her worst films, comedies such as Death Becomes Her and She-Devil. Things have turned around again since then. She shrugs and says, “I’ve always been able to find something, when I’ve wanted to work, that I’ve thought I could apply myself to, that interested me or tickled me in some way.” On November 8 2002, Streep appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show with Nicole Kidman and Julianne Moore to promote their collaboration on a film called The Hours. It was adapted from Michael Cunningham’s pastiche of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway and provided all three women with immensely strong roles. At one point in the show, they fell to discussing their insecurities.

“I just can’t do it,” said Kidman, explaining how she feels before a shoot. “I just don’t want to work, I’m so upset, I’m not going to be able to do this and dahdahdahdahdah, just get me out of it! Get me out of it!” “At the beginning,” said Moore, “I’m scared. In the middle, that’s when I start to doubt my choices; and then by the end I think I’ve ruined it. I’ve ruined it.”

“Wow,” said Oprah Winfrey. “Meryl, you do the same thing?” “I do it all the time,” said Streep. “Why do we do it?” said Kidman. “Well, I know why I do it,” said Streep. “Why do you do it?” “Because I think: I don’t know how to act.”

It was a nauseating piece of self-deprecation from three women at the top of their careers, and I mention it to Streep, the fact that even now she and the other two are… “…even now?” she interrupts. “What do you mean, even now? Especially now. I mean, come on; when you have people writing these things, that you’re the greatest thing that ever ate scenery, you’re dead. You’re fucking dead. How can you even presume to begin a new character? It’s a killer.” She takes refuge from the pressure in her family. Her children are Henry, Mary, Grace and Louisa, the oldest 26, the youngest 15. At the age of seven, her son complained about always being the new kid in school and the family stopped moving around and settled in Connecticut, where they stayed for 20 years. Earlier this year they moved to a loft conversion in Tribeca, New York. “Up in the country, they loved it there and they didn’t want to move into New York. They were scared. And I said, you’re gonna love it, it’s fabulous.” Why were they scared?

“Because it’s a big city and they didn’t know anybody. Kids are very conservative, they don’t want to meet new people. They like their own people.” Streep “deplores” the fact that her children are attracted to acting. “I would love someone to be an astrophysicist or even just a vet. But they seem to be drawn to acting.”

Actually, she corrects, the oldest, her son, is more interested in music. Streep herself has a strong, clear voice and memorably sang unaccompanied over the final scenes in Silkwood. (When she lost the title role in Evita to Madonna, she famously pointed out that her voice is better.) “Completely objectively speaking,” she says, “my son is incredibly talented. And my daughter has just sort of burst upon the scene. Right out of college she’s got a great job in a play, and the first thing she worried about was, did I get this part because I’m your daughter? And I said, you may have got the audition because of that. But nobody is going to put you in the lead in a play that plays eight times a week, for however many months, because you’re somebody’s daughter. And she was great. Now she’s making a movie, in which she has a huge part. She and Claire Danes play sisters. It’s amazing to me.” They lead a relatively modest life. I ask Streep what is her biggest guilty spend and she says, “I had a crooked tooth and I had it bonded.” That doesn’t count. “It cost a fuck of a lot.” What, did she get it done in platinum?

“It was before I had dental insurance. Um. I bought a car by myself, which I’ve never done before. I did it when my husband was away. It was another Prius and since then I’ve bought two more and traded them in and made money on it, so now I feel like a mogul. I don’t spend much on luxuries.” Does she have lots of art? “Yes. But I don’t consider that luxury. I think that’s like food.” Streep’s husband is an artist and although she doesn’t follow the art scene much, she knows what she likes. “Art now seems to have such a didacticism about it; you have to read things, a volume that accompanies the show, to know what the fuck you’re looking at. And it drives me nuts.”

Politics drives her nuts, too. She campaigned for Kerry in the last US election, but thinks that a change is so overdue now that the Democrats needn’t wheel out any movie stars. She talks about the “special loathing” reserved for Hillary Clinton. “From other women, too. Things are really shifting and the position of women is – I’ve always felt this – precipitating a lot of the destabilisation in the world: the rise of fundamentalism is all about fear of women. Fundamentalism in America – some really crazy people are emerging, coz we just don’t know what she [Clinton] might do, if she gets in power and vacillates. Don’t you think we need more of that in the world? People saying, guess what – I think I was wrong, back then, when I made that decision? I made it with the best information I had, but I’ve changed my mind? Too bad that’s not a man’s prerogative.” I suggest that if three male stars had appeared on Oprah that time, the conversation would have been very different. Streep screeches. “Ab-so-lu-tely. First of all, you couldn’t get the three of them on the same show, darling. They’re not going to share a fucking platform. I’d love to hear that conversation.” The irony is that Streep’s modesty is confirmation of her status as top dog; she can afford to be gracious.”I really, really depend on the other actors for the confirmation of who I think I am,” she says. “And so it’s important to me to work with good people that are not worried about how they look. You know. Real actors. They’re your blood. Like in Prada, [Anne Hathaway’s] vulnerability was so palpable that you just couldn’t help but eviscerate her. It’s like an animal that offers the neck. She offered her neck, constantly. So I felt like the alpha dog. The trembling of Emily Blunt; my work is done!” She cackles. “The sycophancy of Stanley Tucci gave me my character. D’youknowwhatimean? I come in, like you say, an unpeeled mollusc, and they give me my authority. It’s a lesson I learnt in drama school: the teacher asks, how do you be the queen? And everybody says, ‘Oh it’s about posture and authority.’ And they said, no, it’s about how the air in the room shifts when you walk in. And that’s everyone else’s work.”

The Devil Wears Prada is released on October 5.

Posted on March 16th, 2025

|

Posted on February 24th, 2025

|

Posted on February 17th, 2025

|

Posted on February 15th, 2025

|

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|