|

Simply Streep is your premiere source on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her the praise to be one of the world's greatest working actresses. Created in 1999, we have built an extensive collection to discover Miss Streep's body of work through articles, photos and videos. Enjoy your stay.

|

|

Two Queens

W Magazine ·

May 2006

· Written by Kevin West

|

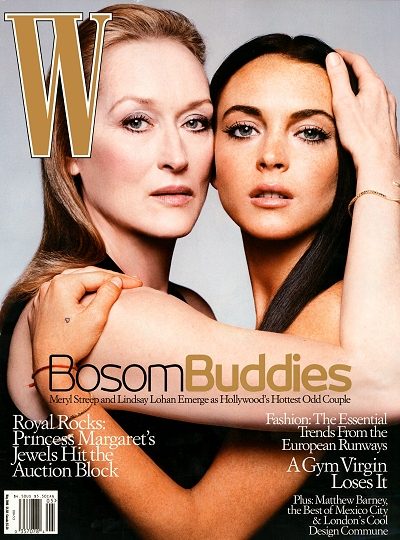

It’s late afternoon at a photo studio in New York’s Chelsea, and Lindsay Lohan is carefully reviewing a little stack of Polaroids at the end of a day in front of the camera. She is pleased with the results, although she does fret about the influence on younger fans of one picture of her with a cigarette. “A girl with asthma, smoking,” she says. “Great.” Of the bunch, her favorite image is the one on the cover of this issue. It shows Lohan and Meryl Streep, her costar in Robert Altman’s A Prairie Home Companion, in an intimate embrace that Lohan likens to that of a mother and child. The double portrait was, in fact, an idea that Lohan herself pitched to the magazine, and she marvels at the contrasts it reveals between herself and Streep-“the old and the new,” she says. One could also say elegance and sex appeal or SPF 40 and Mystic Tan. Suddenly Lohan looks up at the W team. “What are you going to call the story?” she asks, pausing just a moment before she offers her suggestion. “Lady and the Tramp?” The line gets a big laugh-it’s funnier than she seemed to expect-if only because it perfectly captures this moment in Lohan’s rather exceptional career. The former moppet just recently graduated from the Disney academy (last year’s Herbie: Fully Loaded was surely her last kiddie role) and here she is playing Streep’s daughter in a film by one of America’s most esteemed directors.

To date, Lohan, still just 19, has notched up commercial success (Herbie grossed $144 million worldwide) and released two albums, but she is arguably better known as the hottest paparazzi bait among the generation of actresses too young to drink legally. (Not that the law seems to have slowed her down.) If every teenager believes that her personal dramas are matters of national import, Lohan knows that hers actually are, whether the subject is her jailbird father, her boyfriends or her weight. She is understandably ambivalent about her kind of fame and seems anxious to arrive at some future stage in her career when she will look back on these days from a safe distance. “I’d love to be in Meryl’s position,” she says. “I want people to know me for the work that I’m doing, not for this party girl image, which is just vile and disgusting and not fair, because I work so hard. Maybe someone will look at my life one day and say, ‘Why don’t I do a cover with Lindsay Lohan?'” In years to come, A Prairie Home Companion will likely look like just the right film at just the right moment. It not only launches a new, grown-up phase-her next role will be in Bobby, the story of Robert Kennedy’s assassination, with Anthony Hopkins-but also introduced her to an important role model in Streep. “Lindsay hung on Meryl almost like a mentor,” recalls Altman, a director known to love actors and barely tolerate the media. “And she was very respectful of all the people she worked with. It’s the press that makes news of all that other stuff. But I think she’s great and I’d work with her again. She’s a great talent with a really sexy voice.”

The day after the photo shoot, the two actresses plan to meet for lunch at Nobu, with Streep arriving first for a short solo interview. She enters dressed in an ample cardigan and wearing plastic glasses that obscure her nose’s Renaissance splendor, as if she intends to pass herself off as an artsy New York mom. (The 56-year-old actress has four children, ages 14 to 25, with sculptor Don Gummer.) Streep says she was convinced Lohan would be “perfect” for Altman’s film, even before meeting her. “I think I’d seen Freaky Friday maybe seven times,” she says. “I have three daughters, and it’s the Lindsay Lohan fan club at my house. I thought-I think-she is a terrific actress. It’s something that you could see even when she was little-bitty.” A Prairie Home Companion is a congenial film adaption of Garrison Keillor’s long-running radio show of the same name. The movie’s storyline, such as it is, ambles backstage at the Fitzgerald Theater as the show’s cast and crew, including Keillor himself, prepare for their final broadcast. (It’s a fictional conceit: After 30 years, the NPR radio show is still going strong.) Among the film’s most vibrant characters are Streep and Lily Tomlin, who play the two surviving sisters of a famous singing family. Lohan, blond on film for the first time, is Streep’s daughter, a sulky teenager who writes poetry about suicide but who eventually shines through as the face of a new generation-and a pretty reliable hope for the future, at that.

Streep, as if adopting her maternal screen role, is mildly defensive when asked if Lohan’s party exploits ever interfered with her work on the set. “Lindsay knew her lines better than we did,” she says firmly, then continues in a slightly more indulgent tone. “She’s very young. It’s a great sort of coin to have, a wonderful time in somebody’s life. I’m aware of the tabloid stuff because my kids tell me-but I don’t read it, and frankly, I couldn’t care less. When they say ‘Action,’ Lindsay is completely, visibly living in front of the camera, and that’s all anybody really cares about.” She compares Lohan with, of all people, Cher as a young performer. Both actresses have a brazenly confessional manner that leads them to fling away intimate secrets. And yet, Streep says, both are unexpectedly self-contained, and Lohan’s psyche, like Cher’s, has deeper contours than some would expect-guarded places that serve as her storehouse of creativity. “She’s in command of the art form,” Streep says with high seriousness. “Whatever acting is-I don’t know what it is-she’s in command of it. I think she could do anything she puts her mind to.”

A few minutes past the appointed hour, Lohan arrives in a rush and Streep calls out to her: “Hi, Peanut!” But Lohan is agitated and breathless when she plops in her seat, and pulling a knit cap farther over her hair (dark again now), she tells how she was followed from her hotel to the restaurant by paparazzi. Streep gets as flustered as a wet hen. “This is outrageous!” she snaps. Her maternal ire calms Lohan somewhat, but still she doesn’t eat, claiming she had gorged on a late breakfast. (Later, after Streep leaves, Lohan will say that her recent confession of bulimia in Vanity Fair was “not true, or taken out of context or whatever it may be.”) On the subject of A Prairie Home Companion, Streep says that she has been listening to the show for years, and she heartily endorses Keillor’s effort to keep live radio on the air, even if individual shows may be, in her judgment, “hit or miss.” Lohan, on the other hand, had never heard of Prairie Home when she got the part; she called her grandmother for a quick rundown. The radio show, a spoof of small-town Midwestern life, is broadcast from the fictional town of Lake Wobegon, where, according to the Prairie Home mythology, “the women are strong, the men are good-looking and the children are above average.” The movie that Keillor wrote for Altman is like much of the director’s earlier work in that it is less concerned with pushing forward a plot than with allowing actors to play off one another. Keillor says that he adopted the “last broadcast” structure because it was the simplest storyline he could imagine. “It’s a movie that’s not about the story,” Keillor says. “It’s about all these little acting turns, a variety show made into a movie. We’re aware of the story as much as we need to be: It gives us the ending.” The biggest character on set was perhaps Altman, who is now 81. The grand old man had hired director Paul Thomas Anderson (Boogie Nights, Magnolia) as his day-to-day assistant-one who could finish the film if he became indisposed-and found humor in exaggerating his decrepitude, Lohan says. “The first thing Robert said to me when we met was, ‘I’m probably going to croak any day, so this is Paul Thomas Anderson,'” she recalls, adding that she was speechless until she realized he was kidding.

Both Streep and Lohan thought the director was kidding again when he announced that he intended to shoot 10 pages of script in the first day on set. The idea seemed preposterous, Streep explains, since a page or two a day is the typical pace on most shoots. But Altman commenced with Prairie Home’s juicy opening scene, in which Streep, Tomlin and Lohan sweep into their dressing room while talking a blue streak. “We didn’t have time to have any nerves,” recalls Streep. “We were just scrambling for our lives. And when we couldn’t remember our lines, we would just make something up.” “I remember saying, ‘Oh my God, I don’t know if I can do this,'” chimes in Lohan, as she sips ice water. “I was scared to death. But all of these things that weren’t scripted in the scene happened, like when we ended up crying in one of the takes. I have never been happier than after that day.” Lohan pauses, then deepens her voice as much as a 19-year-old girl can to imitate an 81-year-old male director. “That’s adequate,” she croaks.

Streep bursts out laughing and does her own imitation-slightly more credible-and explains that “adequate” is Altman’s highest praise. Despite the director’s crusty ways, both actresses gush about the experience of working with him, and Lohan, especially, was thrilled to be part of an ensemble cast that includes Tomlin and Keillor, as well as Kevin Kline, John C. Reilly, Virginia Madsen and Woody Harrelson. But Lohan especially credits Streep for showing her how an actress ought to comport herself. “One of the main things that I noticed is that she’s so appreciative of everyone who is on set,” Lohan says. “Just the way she interacts with people, always smiling, always laughing, always with good energy. When Meryl comes on the set, it sets the tone for the crew and everyone that day.” Streep, who has received a record 13 Oscar nominations and two statuettes, groans under the weight of this praise as if she can’t stand any more.

In a funny twist of fate, Streep’s next role will take her to a place about which Lohan might teach her a thing or two-fashion’s front row. Streep will play a powerful fashion editor in the screen adaptation of Lauren Weisberger’s tell-all The Devil Wears Prada. Streep did not enjoy being in the fashion world, she reports, least of all dressing the part every day. “I just found it exhausting,” she says, “all the attention to details that might as well have been jet engine parts, for all that I cared. Which bag? Which shoes? Which ring? Which earrings? How does it all look?” A more surprising revelation is that Streep does not model her performance on Vogue’s Anna Wintour, who is transparently the titular she-devil in Weisberger’s book, a work that Streep holds in low regard. “I thought it was written out of anger,” she says, “and from a point of view that seemed to me very apparent. The girl seemed not to have an understanding of the larger machine to which she had apprenticed. So she was whining about getting coffee for people. If you keep your eyes open [in that situation[, you’ll learn a lot. But I don’t think she was interested.”

Streep adds that what fascinates her is the “special venom” that society reserves for powerful women-women like Wintour, Martha Stewart or Hillary Clinton. “The culture wants to cast them as cold,” Streep says, “as if somehow they’ve lost their maternal bearings, their essential womanhood, to occupy this space. As if they’ve had to cut off their…whatever it is…to succeed.” In Lohan’s next screen appearance, in Bobby, she plays a young Vietnam-era idealist who marries men to keep them out of the draft. One of her screen husbands is Elijah Wood, who earns the immortal distinction of sharing Lohan’s first cinematic make-out. “His girlfriend was there,” recalls Lohan. “I felt really bad. And my [12-year-old] sister was there, and I made her walk off set. She said, ‘Ewww! I saw you kissing!'” Lohan’s nine-year-old brother, however, was thrilled to know that Sis got busy with “the guy from Lord of the Rings.”

After Bobby, Lohan is slated for another heavy role, as a girl molested by her stepfather in Garry Marshall’s Georgia Rule, with a cast that tentatively includes Felicity Huffman, Jane Fonda and Shirley MacLaine. Lohan’s character can’t get past the pent-up anger because she doesn’t tell her mother what happened. Still, Lohan promises that it’s not a “depressing movie.” “It’s witty and quick,” she says. “There’s swearing in it and everything, but it’s like what a real family would be. If I were to win an award, I could only hope that people would recognize me for this type of film.” With such statements, Lohan may sometimes let her ambitions run ahead of her accomplishments, but she can be forgiven for believing that she has been groomed to receive Hollywood’s golden baton. Her agent, CAA’s Richard Lovett, also represents Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts. In the lead-up to this year’s Oscars, she met her hero: Madonna.

“I met her at Bryan Lourd’s,” Lohan reports, referring to the A-list pre-Oscar party given by the CAA superagent. “When I first met her, I was in shock and I didn’t know what to say. I looked at her and was like, ‘I love you so much. Can we be friends?’ She’s so cool and down-to-earth and normal, like Meryl. Madonna is someone I would love to tour with.” That same week she took Donatella Versace with her to Teddy’s, and lately she and buddy Natalie Portman are working on a movie idea they would like Streep or maybe Anjelica Huston to direct. Lohan admits her head is spinning pretty constantly, and she insists that she will not let anyone dampen her giddy highs. “I just want to enjoy every moment of it,” she says, winding herself up into a defense of her night life, “whatever way that comes across to people. I’m just doing what I really love.”

As for the ongoing drama with her father, Lohan acknowledges that she hasn’t spoken to him. He did, however, make a bizarre attempt to contact her recently. While she was on the set of Bobby, Lohan reports that her father managed to send an envelope to her-via her stand-in. When she opened it, though, there was no letter, just a return address. The pain caused by the broken relationship with her father is something she tries to suppress. “I use it when I’m singing or acting,” she says. “That’s when I let it out. It’s one thing that I’ve learned to hide. Because my father’s a grown man and I’m his daughter and I can only do so much. You can only worry about someone so much before you’ve washed your hands clean. He’s got to learn that on his own. He’s a big boy. When he’s better, I’m sure it will be the right time for him to come and make amends, and we’ll see what happens.” As a final thought on the subject, Lohan wonders why it is that so many young actresses come from dysfunctional families. She says that not every one of them is “mental” but admits that the gypsy life of the film business only exacerbates most actors’ “schizophrenic” nature.

“I’ve become such an indecisive person,” she confesses, “to the point where [in a restaurant] I order water, regular soda, tea and a drink. I never know what I’m feeling like, and I want to get everything because I’m so used to being so many different people. It’s strange. You go into this movie for two months and you change your whole existence.” At such moments of confusion during the shooting of Prairie Home, Lohan would sometimes find solace with Streep, who seemed to intuit when the younger woman needed a little burst of motherly concern. “She’d pull me aside sometimes and say, ‘Are you okay?'” Lohan recalls. “And I’d say, ‘I’m okay, but I’m dealing with some personal things.’ I’d talk to her about guy issues. And she’d say, ‘You know what? Don’t think about it right now. And if you think about it, use it for how it will help you in the scene.'” But why, then, given the level of trust between Lohan and Streep, doesn’t the older actress take a more active role as a mentor, counseling her, for instance, to skip the parties, stop reading her own press and to think about the long haul?

Streep casts a pitying look across the table when the question is posed to her. As a mother of three daughters, she says, she knows that any sentence beginning with the phrase “You should” will lead a young woman to do the exact opposite. And teaching by example has its limits, too. “You just try to live your life,” Streep says. “If they care to look, they care to look. And if they don’t, no amount of browbeating is going to help.”

Posted on March 16th, 2025

|

Posted on February 24th, 2025

|

Posted on February 17th, 2025

|

Posted on February 15th, 2025

|

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|