|

Simply Streep is your premiere source on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her the praise to be one of the world's greatest working actresses. Created in 1999, we have built an extensive collection to discover Miss Streep's body of work through articles, photos and videos. Enjoy your stay.

|

|

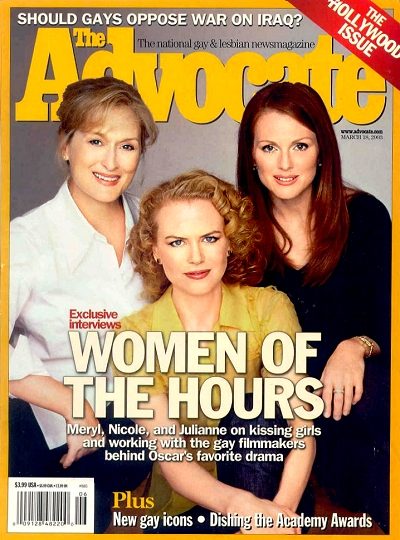

The Golden Hours

The Advocate ·

March 18, 2003

· Written by Michael Glitz

|

|

Tags

|

With Meryl Streep as a lesbian, Nicole Kidman as Virginia Woolf, and Julianne Moore kissing Toni Collette, The Hours would seem to be the gayest movie ever nominated for nine Oscars. But the actresses and filmmakers argue that transcending such labels is exactly what has made the film so successful

“The Hours is not a gay film,” says David Hare, the acclaimed British playwright who adapted Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel for the screen. If by “gay film” Hare means a movie about “the gay experience” that speaks chiefly to queer audiences, he’s right. Since its release in December, The Hours has found enthusiastic audiences (and critics) of all stripes-an adulation confirmed by its nine Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, and three acting nods. But for lesbian and gay observers, what’s remarkable about the golden reception afforded The Hours is that all of its universal themes-the struggle for human connection, the difficulty of self-expression, and the search for meaning-are so inexorably intertwined with the sexual fluidity of its three main women characters.

“I think the sexuality of the movie is very fluid,” says producer Scott Rudin, who thanked his life partner-publicist John Barlow-when accepting the film’s Golden Globe for Best Drama. “I would not say it’s gay or straight. I think it’s really about people who are dealing with issues that involve their sexuality, but a lot of it is unresolved and expressed in other ways. Look, it’s a movie that is fundamentally about people who are thinking of ending their lives. And that is a big, tough subject to deal with in a movie.” It’s true. At the conclusion of its three intertwined tales-set in different time periods-the film climaxes with two characters committing suicide and a third abandoning her husband and young son. Yet through that darkness The Hours reaches a stirring place of affirmation-a moment of pure hope and love that’s encapsulated in a kiss between two lesbian lovers.

For Meryl Streep, who shares that final kiss with The West Wing’s Allison Janney, the characters’ sexuality was secondary to their sex. “Listen, I told Sherry Lansing [the head of Paramount], I think it’s shocking that it’s the first time in [recent] history that a woman-driven film-where women are the actual protagonists and not the girlfriend of somebody-could be considered for Best Picture. And that’s amazing. I think that’s amazing to me.” A woman’s film? A gay film? Embracing its many identities is what The Hours is all about. It’s also about respecting people’s choices as they come to terms with their own identities, says Nicole Kidman, who plays novelist Virginia Woolf in the movie’s 1920s story line. “It’s saying, you know, we have to be really kind to each other,” she adds, “and people make choices [that they need to make].” When Laura (Julianne Moore), a 1950s Los Angeles housewife, decides she must escape her doting husband and doe-eyed son, “that’s judged so harshly in this society,” says Kidman. “But there’s a reason for that [decision], and it’s her reason, and it’s a very pure reason. And it’s a life choice. I just think we all are ready to jump on the [judgment] bandwagon too easily. You don’t have the right to decide how someone else should live their life.”

Moore agrees and goes one step further: Laura’s abandonment of her family, she says, is an affirmation of life. “I think you feel that she chose to live,” Moore says. “At the end of the day, she chose life over death.” The examination of such life choices is the crux of the film’s three plot lines, each set during a single day in a different decade. Streep’s Clarissa is a contemporary lesbian New Yorker preparing for a party to celebrate her friend and onetime lover, acclaimed poet and person with AIDS Richard (Ed Harris)-a task that causes her to question how she lives her life. Moore’s Laura spends her day under the watchful eye of her intense little son while trying to bake a birthday cake for her husband and fend off the desire to escape her life. And Kidman gives her most transformative performance yet as Woolf, kept in an isolated suburb by her husband, Leonard, in the hope that sheer boredom will keep her suicidal despair at bay. As the movie weaves from story to story, all of that inner turmoil is skillfully orchestrated by director Stephen Daldry-to a hypnotic score by composer Philip Glass-on its path to eventual transcendence. “Obviously it’s about three women trying to find change in their lives and their feelings of entrapment or containment or suffocation or loss,” says Daldry. “As they try to break out of that, I think all of these women do reach somewhere else, somewhere positive. What I like about the film is that you’re always aware of the cost of that transformation-the cost of those choices. We all make choices about how our lives should be better or how our lives need to change, but those changes or those transformations or that search for some level of redemption is so often sentimentalized.” In a “gay film”-that is, a movie that could be shunted aside by the mainstream-those choices would revolve around the discovery and acceptance of the precise sexual identity of the three female leads. Is Virginia Woolf a lesbian? Is Moore’s ’50s housewife unhappy in her marriage because she’d rather be shacked up with her perfectly put-together neighbor, played by Toni Collette? And how close to a Kinsey 6 can Streep’s lesbian Clarissa be-despite having Sally (Janney) as her partner-when Richard was the great love of her life?

Such questions are integral to novelist Michael Cunningham’s vision, Hare says. “Obviously you know Michael’s work, and you know Michael,” he says. “Anything that is in the film about sexuality tries to be honest to what the book was about, and indeed what Virginia Woolf herself was about. She could be typed as a gay writer or a straight writer. Virginia Woolf at various times was attracted to men and to women. And I think Michael felt very strongly that he was a gay man who felt the most important relationships of his life and most sexual relationships of his life [at one point] had actually been with women.” Cunningham himself says sexual identity was not at the center of Woolf’s emotional struggles. “It’s hard to know about Virginia Woolf,” he says. “She hardly had sex at all. She had sex with Leonard a couple of times after they were married, and she couldn’t manage it. She had that big affair with Vita [Sackville-West], but she and Vita had sex only a couple of times with kind of the same result. She was a mess.” The fact that the film version of The Hours so defiantly refuses to define or limit Woolf or its other characters owes much to director Daldry’s vision. Sexual fluidity, he says, “just seems so natural to me, so I don’t see it as something that I would have to consider [unusual].” Daldry is, after all, the man whose first film was Billy Elliot, which still has queer viewers debating whether its 11-year-old ballet dancer protagonist grows up to be gay. The film toys with that question-Billy kisses a boy and rejects a girl-but declines to answer it.

Just as Billy Elliot cannot be pinned down as a gay coming-of-age story, The Hours isn’t about lesbians through history. It’s about the desperate need everyone has to control their own destiny, about being open to all possibilities, even those that may defy traditional notions of sexual identity. It’s a theme that Daldry himself embodies: An A-list theater director in the 1990s-his An Inspector Calls won him a Tony in 1994-Daldry did an interview in Out with his then partner, set designer Ian MacNeil. The two later split up, and Daldry married performance artist Lucy Sexton. Cunningham, however, dismisses talk about Daldry’s personal life in favor of praising his innate talent. “I think Stephen’s sexuality is actually as incidental as David Hare’s is,” says the author. (Hare is straight.) “Stephen is fearless, and he’s hugely ambitious in all the right ways. He wants to make the biggest, most idiosyncratic, beautiful things he possibly can. And that’s all I ask for in an artist of any kind.” As Moore warmly puts it, “He’s, like, deconstructed gay.” When asked about his own sexuality, Daldry seems happy to clear the air-perhaps because, now that he’s married, mainstream journalists assume he has disavowed his gay past. “What’s so funny is when people say, ‘Oh, does that mean you’re not gay anymore?’ ” he says. “And you go, ‘Oh, give me a break. What do you mean?’ We wanted to have kids! We thought we’d get married and have kids. We’re allowed to do anything. I refuse to be boxed in to the idea that, Oh, no, I can’t have kids ’cause I’m gay. I can have kids if I’m gay. And I can also get married and have a fantastic life.

“Yes,” he continues, speaking firmly. “To all questions [having to do] with my marriage, the answer to everything is yes. Do I have sex with my wife? Yes. Is it a real marriage? Yes. Am I gay? Yes. “I think about the notion of being gay and the notion of sexuality. You know, you can look at a room with any group of people, whatever the group of people is or however they would define themselves, and it’s so hard to box people in, I find these days. People’s sexuality feels so diverse and so particular and so extraordinary to me that the labels that we try to put on people feel more and more redundant. But maybe that’s just from my own subjective personality.” His frankness served Daldry well in guiding three major performers to some of their best work. Streep embraces one of her fullest contemporary roles; Moore beautifully distinguishes Laura from her other ’50s housewife this awards season, her Oscar-nominated turn in Todd Haynes’s Far From Heaven; and Kidman relishes the chance to imbue herself with the spirit of one of the 20th century’s greatest writers. Losing herself in the role was essential to Kidman, since she feels it can be destructive for an actor to be too attached to his or her real-life self, “to the way you are, who you are, to your identity in the world. I mean, that’s the reason I became an actor,” she says, laughing, “to escape that. I definitely don’t want to be myself.”

Cunningham, for one, was thrilled to see Kidman’s absorption into the part. “I was excited about all three of them,” says Cunningham. “But I think I had the most questions about Nicole. I love Nicole, but could she play Virginia Woolf? Yeah, she was great in Moulin Rouge, but can she play a dazzling suicidal genius?” Kidman goes even further: “A lot of times, when you get told, ‘Oh, this was a crazy woman, or she was mad, or she was incredibly willful,’ it becomes very, very black-and-white,” she says. “And I think Virginia was gray. Everything is about her search and her truth. And I love that she was so truthful about her demons, about her desires, about the things that terrified her, and I wanted to depict that and also her love of life. And Michael [Cunningham] really has summed this up well when he says, ‘This is a woman who as much as she grappled with and thought about death, she loved life.’ ” Striking that balance in her performance has made Kidman the Oscar front-runner for Best Actress, which confirms the impression of many viewers that the she has blossomed from a movie star to an actor of great stature by capturing Woolf’s essence. Describing Woolf as a woman of “fragility mixed with strength,” Kidman credits Daldry’s encouragement for her breakthrough work in the role. It’s a role that could well have influenced the direction of her life. “I’d love to write a novel,” she says. “I don’t see myself doing this for the rest of my life.” Perhaps unconsciously echoing The Hours’ message about the importance of life’s great choices, she continues: “I think I’ll go and move to Europe eventually. I’d love to get my degree in philosophy. So many things I’d love to do: become a really superb cook and have some sort of great bohemian existence where I could live with 30 or 40 people coming and going in a big estate in Tuscany or something.” Like a commune? “I know it sounds ridiculously hippie,” says Kidman, “but I do kind of love that. I love being around people and music and kids. I think we’re too isolated. People go and live in their own little place, and I think it’s sort of nice to be around a lot of people.”

For the moment, though, Kidman is still fielding acting offers, reportedly including Rudin’s The Stepford Wives remake (with a script by Paul Rudnick), the Bewitched movie, and a project with openly gay French director François Ozon. And she’d certainly take a call from Daldry. “I’m dying to work with him again,” she says, not only because he’s good with actors, but “because he is also just kind.” For Streep, much of what Daldry did that made The Hours work took place after the filming wrapped. “Part of the mastery of this was done after the actors were all gone,” she says. “We all did our best. We worked our little heinies off. But I think the editing was just magic. And [Daldry] had a great script. Structurally, it didn’t change [from script to screen]. But that process of how it will all fit together was definitely more exclusive, more separated from the actors.” And the actors, Streep reminds us, were largely separate from each other, doing most of their work in separate cities at different times. “It was a very weird experience to see it eventually,” Streep notes. “It was much less collaborative than other things I’ve done. And that was a little frustrating. But it worked out great.” For David Hare, the fragmentation of Cunningham’s book was a welcome challenge. “I was a little bit spooked by the fact that everybody else seemed to regard this book as incredibly difficult to adapt,” he says, “and I began to think, What’s wrong with me that I can’t see what the problem is? And I think that it’s true that I’m very blithe about subject matter. I’ve written plays about the Chinese Revolution and aid to the Third World. So literary suicide doesn’t seem to me an especially difficult project. But I can see, now that the film is made, that it’s absolutely incredible that a film on such a serious subject is in fact in hundreds of cinemas in America, and that’s basically a tribute to Scott and to Stephen.”

Unusually for a screenwriter, Hare stayed with the film throughout the production, often being on set to trim or tweak or add new scenes. He can’t imagine doing it any other way again. “For me, The Hours was the best working experience I’ve had as a screenwriter,” says Hare. “Stephen has an incredible gift for going to the emotional heart of material in a way that makes ostensibly difficult subjects completely accessible.” That emotional accessibility is perhaps the most crucial achievement in lifting The Hours out of the realm of “gay film” and into the company of more universal literary adaptations. Maybe it’s the film’s seriousness that causes producer Rudin to insist that many of his own lighter, more comic works have a more tangible gay sensibility. “Movies like Sister Act and Clueless and First Wives Club, to me, are much more ‘gay movies’ than The Hours,” he says. Nevertheless, Rudin was savvy enough regarding The Hours’ complicated sexual and emotional themes to hire the one director he thought could make the movie resonate with all kinds of viewers. When he offered Daldry the job, Rudin recalls, “Billy Elliot hadn’t been released. He was still working on it. But I felt the subject [of The Hours] would be personal to him and he would be able to make it smart and political and emotional.” If any aspect of The Hours can be said to best embody that emotional intelligence and richness, it is the echoing woman-to-woman kisses that punctuate the film: Woolf’s hungry, unexpected kiss of her sister; Laura’s thoughtful, caring kiss of her stunning neighbor; and Clarissa’s kiss of her lover, Sally.

As Hare says after dismissing “gay” and “straight” as “fantastically old-fashioned” categorizations, “The three kisses in the film-obviously they’re all ambiguous. They’re not sexual kisses; they’re not unsexual kisses. But [Cunningham] was trying, like Virginia Woolf, to show the way in which sexuality is woven into people’s lives at some quite profound level.” Listen closely when Kidman’s Woolf is about to kiss her sister, Vanessa (Miranda Richardson), and you can hear her gasping for air as if trying to claim Vanessa’s vitality for her own. “It’s this strange act of cannibalism,” Daldry says. “There is almost this need for Virginia to suck the life out of her, to suck the life that she wants-the life in all its varied comforts and confidence-out of her sister. And the idea that that aggression, or that extreme act of need, should be expressed through a kiss just seems perfect to me.” Kidman speaks passionately about that moment: “She needs her, needs her so desperately.” Kidman confesses that she decided for herself what she thought Woolf’s sexuality was-but prefers not to state the conclusion she reached. “However you want to describe the love, the desire for her sister is mixed in with the jealousy [of her sister’s stable family life].” Moore’s Laura also initiates a kiss in part out of envy when she realizes the one thing her neighbor most wants and can’t have-a child-is the one thing she herself wishes to be free from. “It’s also about love, and it’s also sexual,” says Moore. “I mean, the kisses are emblematic in a sense: emblematic of contact, of real, true intimacy-a moment of connection that’s pretty intense. That’s the way we all feel. We don’t take kisses lightly. No one does, really. They’re not casual-to kind of touch somebody that way is a truly intimate, very personal thing to do, so they’re incredibly meaningful, all the kisses.”

Hare agrees. “The film, like the book in a way, is organized around those three kisses,” he says. “That gave a wonderful structure to me as a writer. There were three women getting up, three unexpected visits; there were three crises, three kisses, and then three women going to bed-and the three kisses. When I’ve discussed [the kisses] with people, I think they understand that they’re not one particular thing. Each of those three kisses comes out of profound need.” …ut it’s no accident that the final kiss-the first one that is truly reciprocated-is between two women in a long-term relationship.

Streep says that she loved working with Janney, who created a full character just by walking into a room. “I don’t know how she does it,” says Streep, who lamented the fact that their complex relationship wasn’t presented as fully in the movie as it was in the book. Still, what better proof could there be of the movie’s ability to transcend labels and embrace the emotional vibrance of nontraditional sexuality? Of making choices and connections that fulfill the truths we feel about ourselves? Our reward for diving into the turmoil of Woolf’s mental anguish, Laura’s harrowing decision, and Richard’s brave goodbye to Clarissa is that one passionate connection between two women. “Part of the journey of Meryl Streep’s character,” says Daldry, “is to find and to celebrate once again that the positive things in her life are in fact staring her in the face and so she should look at them.” Hare explains it even more succinctly. “Well, I wanted the third kiss to be a kiss of love,” he says simply, “and, as it were, to conclude the picture.”

Posted on March 16th, 2025

|

Posted on February 24th, 2025

|

Posted on February 17th, 2025

|

Posted on February 15th, 2025

|

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|