|

Survivors: Karen Silkwood

People Magazine ·

March 15, 1999

· Written by Joanne Kaufman, Elizabeth McNeal

|

Many thanks to Samantha for providing this transcript

Abandoned by Mom, Karen Silkwood’s children struggle with a complex legacy

She was a scrappy, 28-year-old lab analyst who somehow had been contaminated with plutonium. She became a national symbol – a martyr, to some – on Nov. 13, 1974, when she died in a mysterious car crash en route to a meeting where she planned to expose unsafe practices by her employer, Kerr-McGee. Two years earlier, though, Karen Silkwood had made a dramatic exit of a different sort that didn’t endear her to anyone: After discovering that her husband, Bill Meadows, was having a affair with her friend Kathy Adams (whom he later married and divorced), Silkwood cleared out of their gray brick home in Duncan, OKla., leaving behind three small children. Before Karen left, Kathy recalls, “she asked me to take care of the kids.”

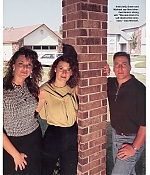

Kristi Meadows, 32, Michael Meadows, 29, and Dawn Lipsey, 28, still have not come to terms with their mother’s death – or her desertion. Gathered in Dawn’s spacious living room in a five-bedroom home in Tulsa to talk publicly about Karen for the first time, three three close siblings take little comfort from Silkwood’s place in history as a whistle-blower who shook the nation’s confidence in the nuclear power industry. “I really, really appreciate what she did for the world,” says Kristi, public relations director for a Chevrolet dealership in Cleburne, Texas. “I can’t appreciate what she did for me, my brother and my sister.”

The last time they saw Karen “was on a Saturday morning, and we were watching cartoons,” Jristin recalls. “I was 5, Michael was 3, and Dawn was 18 months. She said she was going out for cigarettes and would I watch my brother and sister. ‘Keep an eye on your brother and sister.’ That’s all she said.” Months later, adds Kristi, “I can remember hoping and hoping that she would come back and get us. I remember Dad telling us she was dead. I remember being so upset because I knew then that Mom would never come back and get us. That was all I thought – that she would never come back. My mother was gone.”

Though Silkwood’s death was ruled an accident – an autopsy revealed Quaaludes in her system, which may have caused her to fall asleep at the wheel and run her white Honda off the road – unanswered questions prompted speculation about foul play. She had carried a file folder of secret documents to her aborted rendezvous with a New York Times reporter and a union official, but none was found in her car, and there were fresh dents and traces of rubber in the rear bumper and fender. Her children don’t believe her death was an accident. “But it will never be validated, so why worry about it?” asks Dawn, a devoted mother of two boys with husband Richard Lipsey, who manages a Chevrolet dealership. “It’s like how we deal with whether or not she loved us. It will never be resolved.”

Their father, now 52 and a mechanic in Ardmore, Okla., also regrets the lack of closure. “For their sake,” he says, “I wish their mother would have been available to them.” Still, he is glad that Silkwood didn’t fight for custody. “As long as they were with me, I knew they were gonna be alright and I didn’t worry about them.”

Karen “lived on the edge,” explains Kristi, “I don’t think she thought a lot about consequences.” None of her children views her as a saint. “My belief is that she did what she did because she was a troublemaker,” says Dawn. “I don’t believe her intentions were as good as everybody said.” That doesn’t bother Michael, a fiance manager for a Tulsa car dealership and the father of two girls with wife Teresa. “I am proud of Mom,” he says. “Whether she did it to become the kind of legend that she became is not really important. It doesn’t mke up for the loss, though.” He shares his only memory of Karen: “I had gotten up before her and decided to make my own cereal. Instead of using milk, I used soda, and she gave me a little swipe.” He pauses. “It’s sad that you remember a bad one.”

The children were told of Karen’s death two days after Kristi’s eighth birthday. She was riding her new bike when her father called her. “When I opened the door, my dad was holding Dawn, and he had Michael by the hand,” she says. He loaded us in his truck and took us to get an ice pop. When we got back in the truck, he told us.”

“It was a casual thing,” says Michael. ‘Karen died last night.’ It was kind of like hearing that an aunt or uncle had died. I didn’t associate her with ‘mother’ anymore. I associated ‘mother’ with Kathy.” Michael never told anyone who his mother was. “I kept it to myself,” he says. “It’s nothing that I want a whole lot of people to know.”

After Silkwood’s death, her father, Bill, asked Kerr-McGee for $5,000 in compensation for her household goods, all lost to radiation contamination. When the company responded with $1,500, Bill sued. The case dragged on and was finally settled out of court with $1.6 million for the children, minus $1 million in legal and administrative fees.

“I felt it was dirty money, and I spent it as fast as I could,” says Michael of the $160,000 he collected. The three paid off their father’s mortgage, and the girls financed their studies at the University of Oklahoma.

Silkwood’s personal effects are stored in Dawn’s pool house in two white cardboard boxes marked Mom’s Things. The stash is meager: a few photos, her birth certificate and driver’s license, a dried yellow daisy and some costume jewelry. Sorting through it, Kristi looks up at Dawn, who bears a striking resemblance to their mother. “If this was like Oprah,” she says, “and Mom walked in, what would you do?”

“I’d cry,” says Dawn.

Kristi: “Would you hug her?”

Dawn: “Nope.”

Kristi: “I would, but she probably wouldn’t hug me back.”

“Yes, she would,” says Dawn. “I think there had to be some love or else the three of us would not have been as loving as we are. Cause we didn’t just get that from Daddy.”