|

Talent Streepwise

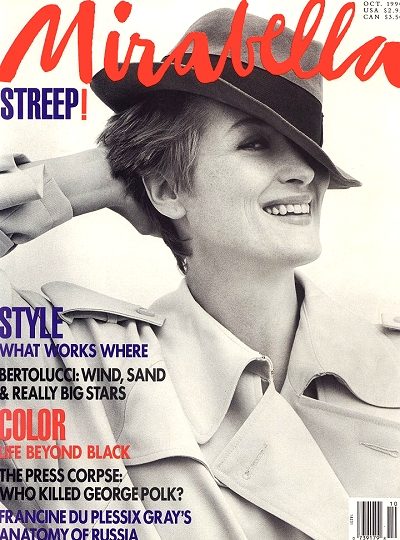

Mirabella ·

October 1990

· Written by Bob Spitz

|

Several years ago, I observed an acting class taught by veteran drama coach Bill Hickey at H.B. Studio in New York City. Two starry-eyed students were in the throes of a scene from The Rose Tatoo, when the teacher suddenly bounded on stage. He had a problem with their approach to the material. Nodding vigorously, the make of the species promptly confessed to breaking six or seven cardinal rules. “How is that possible?” Hickey wondered aloud. “Acting requires that you heed only a single commandment: Thou shalt convince the audience you’re someone else.” Competent actors could learn how to convey that, he assured them. “The hard part, the part that distinguishes mere competence from greatness is convincing yourself.” For Meryl Streep, the line that divides reality and acting has always been an expedient blur. The cameo-faced actress, whose passport to greatness derives from her utterly convincing portrayal of British, Polish, Danish and Australian women, has finally come around full circle with her role as a ready-made Hollywood starlet poised to confront a gaping identity crisis, in Carrie Fisher’s fictionalized autobiography, “Postcards from the Edge”. “I thought it felt more like me and the way I thought than almost anything I’ve ever played,” says Streep, who, oddly enough, hadn’t met her author prior to reading the script. “I looked into all the parallels with my own insecurities and strenghts – as well as my inner voice, which I’m only now beginning to hear and understand in a constructive way.”

Streep might be excused a moment of gratuitous self-exploration. After seventeen films, she remains the screen’s most alluring, if not ubiquitous, personality. Her performances defy all expectations, her range astonishes costars and critics alike, who revel in her illusory power to create an image at the same time that she is creating a human being. Mike Nichols, her perennial director and friend, says the actress’s greatest strength from her ability to transform herself into another person. “When we were shooting “Silkwood”, I saw a screening of “Sophie’s Choice” and I was stunned because I thought we were filming the real Meryl, but the person on the screen in “Sophie’s Choice” was also the real Meryl,” he recalls. “I will never get used to it.” Streep, herself, finds this metamorphosis difficult to articulate. Part of it she attributes to Nichols who, she says, “maked the soup and pours all the ingredients in. I’m just one of them.” The rest remains an elusive struggle. “I always start a film at Point A and I feel I’m without resource or imagination,” she says. “I think: maybe I should take notes, or maybe I should find a method. But since it’s such a mysterious process – making movies, making a character – people imagine that you may have many more secrets and tricks and methods than you really do. The best [actors] start blank.”

“Carrie just told me, ‘She’s all girl,’ so we accessorized a bit more, with rings and things. And I got a pedicure once a week.” She sighs with a hint of orgasmic, if exaggerated, pleasure, then shifts effortlessly into a honeyed Southern drawl: “I don’t normally, in my human life, do that sort of thing. I liked it, though. And I took it right to my next film with Albert Brooks [Defending Your Life, due out early next year]. Of course, then she wanted a pedicure, and the manicurist had to go to his trailer.” She slips back into her native New Jersey vibrato: “Don’t let that out -boy, he’d be mortified.” All of forty-one, Streep has a bio that reads like a page out of Katharine Hepburn’s pressbock; two Academy Awards (eight nominations), an Emmy, an Obie and a Tony nomination. Still, she expresses real concern over the next stage of her career. “The exigencies of the business demand that I take a different approach,” she says with icy resignation. “The trouble is, there just aren’t any stories about forty-year-old women being developed. The screen seems to belong to a bunch of dumb, brawny men – the Die Hard boys. If you’ve noticed what’s in the movie theaters for women and girls, it’s deeply distressing.”

One solution might prompt a return to the boards. To that end, Streep spent part of her summer vacation catching the stage fare in and around Connecticut retreat. “I felt proprietary when I saw Tracey [Ullman] do Taming of the Shrew in Central Park,” she says. “I thought, ‘Hey, that’s my turf! I better get back in there.’ When you see something really wonderful in theater, it stays with you for life. It’s a hotter medium. Movies never come that close.” Close, to Meryl Streep, denotes verisimilitude, honesty. Her speaking voice is naturally blithe, but it contains a bluff note that swings back and forth between wryness and deadly candor, depending on the subject. She’s tart and fast when it comes to studio heads (she calls them “the big boys”), action films (expletive deleted) and story editors (“development girls”). But broach politics or the environment and you trip an emotional wire.

“I don’t want to be a spokesperson for your consciense,” she says, responding to a question about her recent activism. “But when you’re famous, I don’t think you shouldn’t be indemnified from speaking out on the issues.” Streep is particularly pleased about her efforts on behalf of the National Endowment for the Arts and the Brazilian rain forest. And, of course, her successful crusade against the use of the pesticide Alar on apples has been well documented. Still, despite a tendency to “make noise”, she resists offers from public-interest groups that might mistakenly cast her as the Jane Fonda of the nineties. Meryl Streep might take on difficult, life-affirming roles, but as far as upcoming projects are concerned, she insists: “I’m not going to be Joan of Arc.”

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|

Posted on November 7th, 2024

|

Posted on November 1st, 2024

|

Posted on October 10th, 2024

|

Posted on September 26th, 2024

|