|

The Feminine Mystique

Premiere ·

December 1989

· Written by Terri Minsky

|

Ruth Patchett is short and dumpy and has an unsightly brown mile on her upper lip. She does have many fine qualities; she is, for instance, nurturing and well-meaning and patient, but to appreciate these things one must first get past her appearance, and this is difficult to do. She is not the sort of woman that men fall in love with – not even her husband, who married her because she was pregnant. She tries to be the kind of wife he wants, but it is hard. He is attracted to the pale, fragile, glamorous type and Ruth is the dark, stout, clumsy type. When she shops for a new dress, she finds the selection in her size meager and garish. When she stops at the cosmetics counter, she gets her face pulled and pinched by the salesgirl in a hopeless search for cheekbones. She is not oblivious to these indignities, nor does she suffer from them; she thinks such is her lot in life. Ruth Patchett is not Everywoman; rather, she is Everywoman’s worst self-image nightmare, the one about being undesirable and undesired. She is explanation made flesh for anorexia or bulimia or plastic surgery or liposuction or diets consisting of water, grapefruit and Dexatrim. As much as women do not want to be Ruth Patchett, they identify with her because in the end, she avenges them – all the ones who have loved and lost, all the ones who have been seduced or abandoned. Their agony, their terror, their pain becomes her fuel, her inspiration, her reason for revenge. As such, she may be seen as an archangel; instead, she is called the She-Devil.

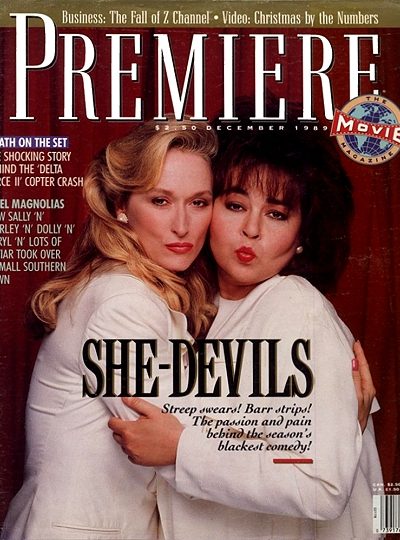

Agony, terror, pain – a woman screams: “Owww! OWWW! YYYAAAHHH”! Roseanne Barr is having her toenails painted. She is sitting in a beauty-parlor chair in Hackensack, New Jersey, on location for her first movie, “She-Devil”. She plays Ruth Patchett, an ugly woman who loses her husband to a beautiful one and then dedicates herself to making them as miserable… no, more miserable than they’ve made her. At the sound of Barr’s keening, the pedicurist’s hand freezes in midair, a drop of pink polish suspended from the tiny brush. Barr englightens her tormentor. “I can’t stand nobody touching my toes”, she says. “I have a real phobia about it. Like at night when I sleep, I have to have my toes sticking out from the sheet. I can’t have them covered. That drives me beserk.” She pauses to see whether this line of argument is having any effect, then tries another. “Plus I don’t think my feet smell so good either.” The pedicurist does not mean to torture Barr, but she has her instructions. The pampered digits are needed for a tight shot – a pan up from the toes to a hand being manicured to Barr beneath a dryer, her hair wound painfully in performing curlers; a woman wanting to look nice for a rare night out with her husband. In the case of Ruth Patchett, this proves to be a touching but ultimately hopeless effort. The pedicurist moves the offending bristles toward Barr’s foot. “I’ll do it real quick,” she promises. “One coat.” “Oohhhh, I’m in hell, I’m in hellllll,” Barr wails. If Roseanne Barr does not endure this personal purgatory gladly, she does endure it for a reason: Ruth Patchett. She, Barr, is Ruth Patchett – a woman who must discover her own strength and ingenuity when the rest of the world assumes she has neither. But director Susan Seidelman wanted to make “She-Devil” because she, too, knows Ruth Patchett, knows what it feels like to be an underdog, to thirst for revenge. Even Meryl Streep, who plays the nemesis, romance novelist Mary Fisher, feels close to the homely Ruth Patchett, because the She-Devil manifests Streep’s resentment of the premium her profession puts on appearance. Because of Ruth Patchett, Streep passed up the opportunity to reteam with her “Sophie’s Choice” co-star Kevin Kline, in director Lawrence Kasdan’s own spousal-revenge film “I Love you to Death”.

It is difficult to imagine that one fictional character could have united so unlikely a triumvirate of talent; a classically trained actress whose ambitious start turns have earned her an Oscar nomination (if not the actual award) almost annually; a director given to small, quirky projects; and a comedian born of stints in a state of mental hospital, a trailer part, and biker bars. Indeed, such is the power of Ruth Patchett – she is unique among screen heroines. She is not a role model. Unlike her cinematic sisters in, say, “Broadcast News” and “Working Girl”, or even such classics as “Mildred Pierce” and “All About Eve”, she does not subscribe to the notion that she would be happy if only she had a fulfilling career or the right man. Rather, Ruth Patchett is an emotional vigilante for all that is inherently unfair about being female: that women are expected to strive for an almost unattainable ideal of beauty; that their childbearing years are limited; that being a mother and a homemaker is not considered meaningful work; that there is always the fear of being replaced by someone younger, prettier, more talented, more lively. The attitude is so indigenous, so pervasive, among women that the story of the “She-Devil” was dreamed up by a happily married British author with four children – even she found herself lying in bed in the middle of the night, scheming what she would do if her spouse ever left her. Fay Weldon’s resulting novel, “The Life and Loves of a She-Devil” detailed an obsessive, decade-long campaign of revenge, culminating in Ruth Patchett’s undergoing total-body plastic surgery to have herself remade in the image of the woman who stole her husband. (For the movie, Seidelman decided against this macabre twist because she liked Ruth and didn’t want to lose her.) Ask a man, ask the producer of “She-Devil”, Jonathan Brett, if he’s ever plotted revenge, and he tells a rather pathetic tale about wanting to get back at the guy who cut him off in traffic that morning. Now, a woman could spin a much more creative fantasy. Meryl Streep, for instance, has one: “There’s this person who wrote a book about me, and it was very stupid and used all sorts of other interviews that I’d done over the years. She just went through magazines and made this sloppy thing, put my picture on the cover and sold a book for herself. So I thought about finding out where she lived and putting a dead fish somewhere in her windowsmill. You know, somewhere in the wall. I was hoping that it was some fabulous rent-controlled apartment. Where you could just – you didn’t know where the smell was coming from, but you couldn’t live there anymore.”

For a while, Streep considered taking the part of Ruth Patchett herself; she was one of the first actresses to read the script, because she and Seidelman share the same agent, Sam Cohn of ICM. “He wanted her for Ruth, but I was hoping she’d be Mary,” says the director. “When he called me to say, she’d do it, I didn’t know which part he meant.” It would have been very difficult to deny Streep the role, and Seidelman sounds relieved that it didn’t come to that. “If she had wanted to do Ruth – I don’t know, I don’t know. It’s a weird thing, because she could have played Ruth. But I dind’t want an actress who had her clothing stuffed, or had to gain weight. I mean, the thing about Roseanne is that she’s not playing a fat person.” Streep does have this thing about the feminine ideal – the inappropriate value placed on being young and thin and pretty. “I really don’t like thinking about it,” says Streep, with her silken hair and luminous skin, as she repeatedly extends one perfectly proportioned calf in a sort of dancer’s stretch, running her hand down the length of it. She goes on: “And a large part of my adolescence and all the way up until last year, or right now, all the time I’ve wasted thinking about it,” But she passed on Ruth because she felt she had dealt with that subject in her previous project “A Cry in the Dark”, a true life story about an Australian woman accused of the murder of her baby. “You would never think that was an issue in the movie, probably,” Streep says, “but to me it was. How she appeared. How she held herself and behaved and looked and dressed had a lot to do with how people judged her as feminine or not feminine. How her own husband judged her as too fat.” Instead, Streep felt she could do her bit to debunk the ideal by turning Mary Fisher into a caricature of femininity. Everything about her is pink, from the perfectly manicured nails (in reality, Lee Press-ons) to her frilly, flouncy wardrobe – even her maison by the sea. “I thout I was going way, way, way out on a limb with this character,” says Streep. “Meanwhile, I hadn’t turned on the television for a while. The way I look in this movie, as outrageous as I think I look, I look like everybody on TV. And these are the models that our little girls watch. I mean, it’s back to Barbie dolls, basically.” Evidently Streep is not familiar with her costar’s hit television show. But Barr’s portrayal of an overweight housewife did not instantly make her a candidate for Ruth Patchett. In the novel, Ruth is both heavy and extremly tall, but Seidelman despaired of finding both traits in a single person. “Unfortunately, it’s hard finding a less-than-perfect-looking actress in Hollywood,” she says. “We thought about going with an unknown, but then it becomes a Meryl Streep movie, and you want these two women to equal each other.” Her first inclination was to look for someone with height rather than weight – she thought of Anjelica Huston, but she knew the actress was unavailable. At the time, Barr had been reading scripts in search of one she considered appropriate for making her feature debut. “I got a lot of stuff where the woman’s happy ’cause she lost weight or she got the guy, and it just seemed really demeaning and degraing. I wanted something with some kind of soulful thing of upheaval and truth-telling.” When she found it in Ruth Patchett, she made her own peculiarly passionate plea for the role. Her words of greeting to Seidelman were: “I’ve never said this to anyone before in my life, but I’m gonna say it to you: if you give me this part, I’ll let you fuck me.”

Ed Begley, jr., who plays Ruth philandering husband, Bob, learned early in the shoot what being in a movie dominated by women entailed. There’s a scene in which Ruth arrives unannounced at Mary’s mansion to leave her two unruly children in the care of their father and his mistress, who are at that moment enjoying a nude Jazucci bubble bath. Bob, infuriated by this glitch in his paradise, pursues Ruth to her waiting cab, clutching a towel around his waist. “According to the script, I hurl a rock as the taxi pulls away, and I scream, ‘Come back here!’ But then a motion hit the floor – and this was not in the script – that I should also drop the towel,” says Begley. “And I go, ‘Oh?’ And the three of them are like, ‘Yeah. It’s a women’s movie. We want you to drop the towel.’ What can I say? We could never, in six lifetimes, equal the amount of times the woman has been asked to drop the towel. Well, I don’t know about happily, but I did it.” It’s hard to imagine that Barr, Streep, or Seidelman would call “She-Devil” a women’s movie, except as a joke – none of them, Seidelman in particular, likes the phrase. “People don’t ask Barry Levinson if he makes men’s movies,” she says. “I just pick things that appeal to my sensibility, and I happen to be a woman. I, personally, don’t understand why a woman would be drawn to make “Pet Semetary” (which was directed by Mary Lambert) or even “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” (directed by Amy Heckerling) – though I did like that – unless she believed she had to be as commercially successful as men, which I don’t.” Nevertheless, she does know from experience how rare a sight female filmmakers still are. During the shooting of her third feature, “Making Mr. Right”, one of the Teamsters thought the diminutive Seidelman was a crafts-service assistant and frequently ordered her to fetch coffee for him. She did it, but only because the mistake amused her. Streep, however, does not find the inequities between men and women in Hollywood entertaining in any way, particularly when it’s suggested that her critical acclaim often doesn’t translate into success at the box office. “Can I just tell you that $11 million is what Jack Nicholson got for Batman. Evelen million. He was in “Ironweed”, if you recall. Okay. All right. He was in “Heartburn”, if you remember. Okay. Why does he go into the negotiating thing… I was in Out of fucking Africa, remember? Kramer vs. fucking Kramer! Deer Hunter.” Her voice retains its musical lit, but the passion shows in the way her pale skin begins to flush and she leans forward on her elbows. “I’m saying it’s a guy’s game. If I asked for $11 million, they would laugh. In my face. I make enough that nobody’s gonna weep on my side of the table. But it’s outrageous. I love Jack” – this is said very sweetly. “I’m happy for him. I know he’s laughing all the way to the bank when he makes these deals. But there are different rules for men than for women. I know it’s true. I’m not angry. I guess I’m angry, but not angry enough. I have a great life. If I were starving, I would be doing something about it. I’m not, obviously. And probably that plays against me in that whole negotiating process. But it stinks.” Streep recently pulled out of a long-standing plan to star in Oliver Stone’s movie version of “Evita”; reportedly it was at least partly due to a dispute over the financial terms of the deal.

Meryl Streep and Roseanne Barr have almost no scenes together in “She-Devil”, and the set has a remarkably differen personality depending on which of them is working. When Streep is on, there is an air of formal efficieny. She shows up for a shoot in character. She’s superior, haughty – it’s a scene in which Mary Fisher suffers the first humiliation of a career in decline. A book singing for her latest novel, “Love in the Rinse Cycle”, goes badly; people walk by her table without so much as a glance in her direction. Between takes, Streep remains aloof from the rest; she is audibly only when speaking her lines, keeping her between-take conversations with her director, her makeup man, and Begley hushed and private. She inspires deference, as if she were a guest of honor. The caterer seems grateful that she will eat his food. He had feared that she would want only organically grown produce (Streep has campaigned against the use of pesticides). When she does make a special request, as he has today – for a bran muffin and red raspberries – a production assistant worries that she has filled the order wrong and repeatedly asks her colleagues if there is a difference between raspberries and red raspberries. Crew members like to collect pictures of themselves with the stars of the movies they work on, but by the final week of the shoot most are still too intimidated by Streep to ask her for this favor. Plus they have heard that she’s very protective of her photographed image – it has been said that if she doesn’t approve a color slide for a publicity release, she will burn a hole in it or cut her face out of it. One set photographer did not enjoy seeing his work mutilated in this way and asked her just to return the empty slide sleeves. “She’s so smart, it makes you a little nervous,” says Seidelman of Streep. Barr calls her “a god, a goddess. I don’t need that many scenes to see her, she’s so visible. You can just feel her everywhere. She kills me, she blows me up so far away, she’s just so great.” (Streep says of Barr: “We had a dinner a couple of times. I like her.”) Begley still seems stunned that he gets to play Streep’s lover; one, during a break, he makes a joke to her at his own expanse: “You may be dismantling a very illustrious career here,” he says. On the other hand, Barr makes set a noisy playful place. Between takes she waves to the onlookers, signs autographs and invariably whines, “Who’s got a cig?” She is given to physical, if sometimes painful, displays of affection. She greets people with a sock on the shoulder, and during a break in the beauty-parlor shoot, she engages Seidelman, whom she genuinely admires, in a wrestling match on the floor. Her special request for food is somewhat more exotic than Streep’s: popcorn doused with hot peppers, which Barr thrusts on anyone who questions is edibility. (One gets this feeling that she may be familiar with the culinary analogy Begley uses to describe his costars: “Kiwi with beanut butter.”)

The crew is not too intimidated to ask Barr for a picture; if anything, they have to discourage her posting proclivities. At one point, when a sound man adjusts a microphone at the hem of her skirt, she holds his head near her crotch and waves the still photographer over to record the moment. “I want your wife to see this one,” she says, cackling. The difference between the two actresses are at least partly a reflection of the divergent paths each took to arrive on this set. To paraphrase Shakespeare, Streep achieved fame, and Barr had fame thrust upon her. “I don’t think she came to movies or theater from the angle I did,” says Streep of Barr. “When I was in school, people talked about being a transforming actor, and that appealed to me. I struggled through all sorts of Brecht and crazy things that our friends were writing, and Shakespeare and Chekhov. I like that. But Roseanne’s come up sort of boom, all at once. I don’t think one way is better or any more or less effective – whatever gets the job done.” Ironically, Streep’s reserve belies the fact that “She-Devil” is a lark for her, whereas Barr’s playfulness masks her own deep involvement with Ruth Patchett. “It feels really great to not have it cost one of our limbs to do a movie, like other things I’ve done,” says Streep. “Oh, the cost, the emotional cost, in doing things that are more grueling, this is not something that upsets you and keeps you awake at night, gives you nightmares, like “Sophie’s Choice” or “A Cry in the Dark” did. “A Cry in the Dark” gave me terrible nightmares. I would dream in character. And “Plenty” was hard, that was a screaming-brain kind of movie. Screaming brain – I’m sure I stole the image from this next movie I’m doing, “Postcards from the Edge”. I think there’s a line: “I feel like I’m up in the tower of my own brain, screaming to be let out’, or something. But this is not that. This is not that at all.” When Barr discusses the movie, she does it in a voice several registers deeper than her trademark nasal monotone, as if to send and aural message: this is serious. “Ruth has to go through a whole self-catharsis shit, and that doesn’t come from just somebody hurting you or dumping you,” she says. “When her husband tells her he’s leaving, she realizes she gave her whole life for nothing. And I’ve felt that; what a fucking waste of my life that it came to this. And you have to go through all this self-upheaval and own all your shit. Just to take responsibility and go, ‘Now it’s my time,’ Those are hard things to do. See, this movie’s happening at a really perfect time in my life, ’cause I’m doing that too. I felt that I’ve learned so much from being Ruth and from playing Ruth that I’ll be able to use it forever.” There is another character whom Roseanne Barr would really like to play in the movies: herself. She has dreams of dramatizing her own life history in the way she feels Woody Allen has done in his films. “I want to be Woody Allen so bad,” she says. “He’s my hero. I’d like to make movies like he does, where basically you tell the same story a million different ways, over and over.” In the meantime, there is Ruth Patchett to think of. A wardrobe fitter comes to Barr’s trailer with two dresses for her to try on – an offensively lould floral print with huge dolman sleeves and a dropped waist, and a simple black sheath with thin gold straps. They’re for a scene in which Ruth shops for a dress to wear to a party – the very party where she will lose her husband to Mary Fisher. Barr strips down to her bra and slip and pauses a moment to admire herself in the mirror. Of the three of them – Barr, Streep, and Seidelman – she is the only one who is completely happy with the way she looks. “I have a great body,” Barr says. “I do have great legs. And great tits.” Indeed, shed of her clothing, she is compact and well-proportioned. Barr pulls the first dress over her head. She hates it. “This is really the grossest fucking mall dress of all time,” she says sourly as she observes herself in the mirror. “I look like Rosemary Clooney”. She pulls the elastic waistband up and down in an attempt to find a way to tighten the draped, girth-disgusting bodice. “I don’t like this,” she says. “I think if you’re fat, you should fucking be fat. Just be fat and shut up. I would never wear anything like this, that hid it. I wear belts.”

The second dress, the black one, is three sizes too small – the back won’t even begin to zip. “Well, that’s good, that’s what we want,” the fitter says. “The whole point is you’re trying on dresses that don’t fit.” “But I like this one,” says Barr, appraising her reflection. She slips on a matching black jacket, covering the uncooperative zipper. “I really like it.” “Oooh, the jacket is terrific,” the fitter agrees. He hesitates and then asks. “Would you, um, do it without the jacket?” Barr takes it off, showing her exposed back. “Like this”? “Yeah”. “You want me to turn around so you can film this?” The fitter seems embarrassed by his own suggestion. “I dont’t know if Susan wants to go that far,” he says, taking in the expanse of skin and underwear. But the whole bit is supposed to be that it doesn’t fit you.” He pauses. “You know, with the jacket on, it looks good.” “Yeah, all right, if she wants it,” Barr decides. “You know, I was gonna be nude in the movie, before they changed the script. But someday, I definately am gonna be naked in a movie.” “But not this one,” the fitter says. “I would have done it,” she says. “I think I look good. I want to do it as a political statement. I like to show my body.” She tells him a story about how she and one of her sisters took a picture of themselves in scanty lingerie. She left the photograph in her hotel room, and when she returned from the set that evening, it wasn’t there. “That was about two weeks ago, and I’m expecting it’s gonna turn up someplace real ugly.” The fitter wants to see her again in the other dress. “I wanna wear it like this,” Barr says, hiking the calf-length skirt up to the micro-mini level. “I have great legs, don’t I”? “You certainly do,” he tells her. Roseanne Barr is short and dumpy, and she has an unsightly brown mole afficed to her upper lip to play the role of Ruth Patchett. She knows that her character is supposed to be unattractive, but Barr does no think of herself that way. She is going to teach this to Ruth Patchett. She is going to teach this to anyone who wants to know.

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|

Posted on November 7th, 2024

|

Posted on November 1st, 2024

|

Posted on October 10th, 2024

|

Posted on September 26th, 2024

|