|

The Making of Ironweed

People Magazine ·

January 18, 1988

· Written by Michael Ryan

|

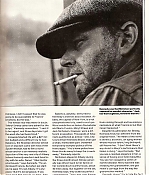

The poor and the beaten inhabit his head, the clever and the crooked take their voice from him, and the dead souls of Albany, N.Y., roam through his consciousness on endless, unsatisfying quests. William Kennedy is a sharp-cornered man, not given to mawkish sentiment. A few feet above this sitting room, where a bottle of cabernet is racing the afternoon sun to oblivion, the gangster Legs Diamond was murdered, but that fact is neither raised nor commented upon. It simply exists, as the hard realities of life exist, unchallenged and immutable, in the pages of Kennedy’s fiction. This is not a place of soft emotions or easy enthusiasm. Until the talk turns to Meryl Streep.

“She’s terrific,” says Kennedy, 59, with an ardent voice, a reminder that, before he had a Pulitzer Prize and a place in the pantheon of American letters, he was a screenwriter and an unabashed fan of the movies.

Hollywood has done what seemed impossible: It has transformed Ironweed, Kennedy’s dark, unsparing comedy of the Albany underclass, into a movie that the author finds impeccable. But then, he wrote the screenplay too. Some critics have complained that the film does not achieve the metaphysical transcendence of the book, but Kennedy insists that is not what he set out to accomplish. The movie is “exactly what/ had in mind,” he says. Streep and Jack Nicholson took on the roles of Helen and Francis, the tattered Albany street people on a Depression-era progress through love and loss to drink and death. The film, as directed by Hector Babenco, glamorizes nothing.

“A lot of people wanted to play Francis,” Kennedy admits. “Gene Hackman, Jason Robards and Sam Shepard were early possibilities. But Nicholson had that toughness, that Irishness. I didn’t expect that he was going to be susceptible to Francis’ emotions, but he was.”

The female star was never in doubt. “Meryl Streep called and asked for the script,” Kennedy remembers. “I sent it to her agent, and three days later I got the word she had been hired.”

Ironweed started life with a $27 million budget and a difficult row to hoe: Babenco, the Brazilian director whose lock on stardom came with Kiss of the Spider Woman, had to film a novel whose anchor is an intensely realistic depiction of the very real city of Albany (where Kennedy was born and lives today with his wife, Dana). “I like Hector enormously,” says Kennedy. “He understood Francis. But when we started, he said, ‘It’s not Albany. It’s anyplace.’ But it’s not anyplace. If you don’t have that specific location, then the characters become fantasy, mythic, kind of free-floating creatures.”

Babenco, astutely, demurred to Kennedy’s instincts about location. Albany, the capital of New York, is a not unsophisticated city, used to such political celebrities as Nelson Rockefeller and Mario Cuomo. Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson, however, were a different proposition. Thousands of Albanians auditioned as extras—one, City Councilman Nebraska Brace, even got a small, memorable part. Ironweed temporarily bumped politics off the front pages. “You’d have police lines three blocks away to keep the crowds away,” Kennedy reports.

Nicholson stayed in Albany during the three-month shoot; Streep generally was driven back to her family at her Connecticut country house, about 40 miles away. But together on the set, Kennedy says, they acted as perfect complements. There was, says Kennedy, “the matter of keeping that wild character Jack played in The Shining from coming through and becoming a caricature of what Francis is; but that never happened.”

Despite his admiration for Streep, Kennedy finds her different from the original Helen. The Helen of the novel is derelict, alcoholic, an aging woman whose musical talent, long betrayed, still haunts her. “I don’t think there’s any doubt in Meryl’s performance that Helen is dying,” says Kennedy. “But you see a residual elegance in her, a sense of having once been beautiful. You see her ravaged by some unnamed disease. Meryl said she was imitating her grandmother; she got Helen’s carriage from the way her grandmother walked.”

Kennedy doesn’t try to hide the fact that his Ironweed screenplay had liberal input from its stars. Nicholson himself is a former screenwriter. He has vigorous opinions on the subject and no temerity about expressing them. “Sometimes I made the changes he asked, sometimes I didn’t,” says Kennedy. They disagreed over a scene in which Francis has a fight with Helen on the street. “They clinch, and she says, ‘You gonna hit me?’ and he says, ‘Nah, I love you some.’ Jack didn’t want to say ‘I love you.’ He didn’t think you could say ‘I love you’ in the movies anymore.” In the end, “Jack did it the way it was written.” Kennedy says that Nicholson was concerned about playing what he considered his “most complex role” to date. “Jack has never gone as far out, he’s never had to be this destitute a character.” (The risk paid off: Nicholson was voted the year’s Best Actor by both the New York and Los Angeles Film Critics.)

Nicholson’s co-star also made her mark on her character. “Meryl had an idea to find more than was written in the script,” says Kennedy. “She made it more intensive.” He thinks the scene that almost steals the movie belongs to Streep. Helen, dying, desperate, torn between the horror of her life and the beauty of her abandoned past, wanders back to the Gilded Cage, a honky-tonk where late her sweet voice sang. Though she is filthy, ruined, old, the bartender invites her to sing, and she does, a 1905 song called He’s Me Pal. “It’s a tune my mother taught me,” Kennedy says. “A great, old Tin Pan Alley music-hall kind of song. It’s got two verses, and she sings them both.” In fact Streep—who once took voice lessons from an opera coach—does her own singing in the film.

Kennedy and his wife appear as extras in the bar scene, and they watched all 18 takes of it. “She’s over the hill in every way,” he remembers of Streep’s Helen. “But she’s rejuvenated by the chance to sing again. She did this song 18 times, and the sight of this talented actress just galvanized everyone. There was an incredible response from the extras and the crew—everybody was crying.”

Although he has been recognized in recent years—after decades of thankless toil—as one of the ornaments of American literature, Kennedy says he had no vanity about changing his original script to meet the actors’ needs. “Why should it piss me off?” he says. “We’re here to make the best possible movie. I’m a neophyte in this business, a marginal character—probably always will be. Nicholson has made more than 40 movies. Streep is the supreme actress of our age. If they see something that will enhance the role, why not? This is the movie. They’re not telling me how to write the book. I already did that.” Whether or not the film fulfills people’s expectations, Kennedy takes solace in an immutable fact: “My writing is still there,” he says. “They can always go back to the book.”