|

Streep's Choice

The Mail on Sunday Magazine ·

April 1983

· Written by Joan Goodman

|

Because her role in “Sophie’s Choice” now seems made for her, it’s hard to imagine how close Meryl Streep came to not doing it. She had been director Alan Pakula’s first choice for Sophie but when he flew to England to see her on the set of “The French Lieutenant’s Woman” and offered her the part, they fell out. “He said I couldn’t read the script; that it wasn’t ready,” Streep recalls. “And I said how could I say yes without reading the script?” He said “I’ll tell you the story.” I said, “I know the story, thanks.” He got mad at me and I got mad at him and we parted company. He said, “I’m going to look elsewhere.” And I said, “Well, you’ve got to.” And he did. Pakula, who also directed “All the President’s Men” and “Klute”, was obsessed with finding a European actress for Sophie. He all but gave the part of Czechoslovakian actress Magda Vasaryova. However, before any formal arrangements have been made, Streep got hold of the script, read it and realised she had made a dreadful mistake in turning down the role.

“My agent got me to see Alan, on my knees, to apologize for being so flippant about the offer in the first place – and to please, please, please give me another chance.” Streep laughs ruefully at the memory, accepting the humbling experience as her just deserts. “Alan had this Czech actress’ pictures on the wall of his office. I don’t mean two pictures, I mean maybe 20 pictures, all different poses of her. But he listened to me. He not only listened, he said ‘Come back next week and we’ll talk again.’ I came back – twice. Then he let me sit by my telephone for two and a half weeks before he called me.” Streep shudders and shaked her head grimly. “My mother says that sort of thing is good for the character. It doesn’t feel good, but it probably is.” An Academy Award nomination feels much better. “It’s a great honour to be recognized by your peers”, she says, then wrinkles her nose with distate and adds, “though I must say that I am not in love with those ceremonies. I get real nervous.”

To me, Streep is marvelous as Sophie Zawistowska, the complex, romantic, tragic figure taken from the William Styron novel about a Polish Catholic survivor of the Auschwitz concentration camp doomed to eternal heartbreak. She is in turn voluptuous and spare, exuberant and sodden, passionate and pensive. Every extreme of mood and temper flickers across her face and in her delft-blue eyes. So complete is Streep’s creation that she seems almost to will her body into a kind of middle-European plumpness. In the film’s lighter moments, we see her flair for comic invention. She and her lover Nathan Landau (Kevin Kline) dress in 1920s period finery and cavort to music for the amusement of their new-found friend Stingo (Peter MacNichol), the would-be-writer from the South who moves into their Brooklyn boarding-house, and eventually tells their story.

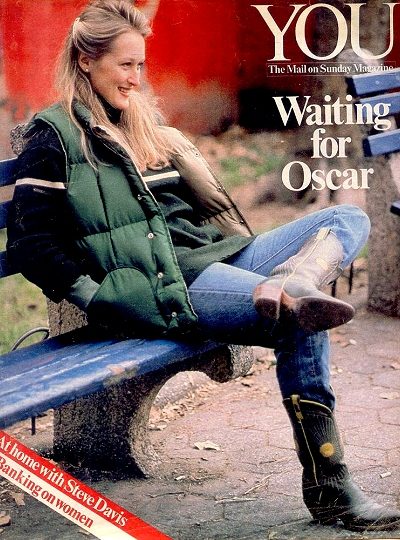

Streep’s way with a single world in the impeccable Polish-inflected English she uses as Sophie is often a pure delight. Her line reading and misuse of words are great fun – “Can I make you a night hat?” she asks Stingo. Sophie is the part of a lifetime and Streep plays it for all it’s worth. “I loved it from beginning to end”, she told me in New York, tossing her pale blonde hair back from her face. “I thought, it’s the most fun thing I’ll ever do. Everyone asks, ‘Did it take everything out of you?’ But roles like this nourish you.” Nothing in her background prepared Streep for the fame that has come her way. Born and raised in New Jersey, she’s from a solid middle-class family. Her father, a pharmaceutical excecutive, her mother, a commercial artist, gave Streep and her two younger brothers a healthy dollop of culture – theatre, films and concerts. “It was a cheerful childhood.” Streep was bossy, wore braces on her teeth, and glasses. All that changed at high school. She discovered peroxide for her hair and a glorious coloatura voice. She got rid of the glasses, threw away the braces, became a cheerleader and was named the school Homecoming Queen.

At Yale she decided she wanted to act. And once she got to New York, her career went like an express train. “Meryl was amazing,” recalls a fellow actress. “When I heard her reading for the part of a character from the South I though, ‘My God, she’s terrific, but what an accent! I was sure she was fresh off the bus from Georgia. I was stunned when I heard she came from New Jersey.” Streep’s talent for accents was put to full use in “The French Lieutenant’s Woman” with its Dorset dialect. For “Sophie’s Choice”, she did a two-month crash-course in Polish, which enabled her to speak the language in the flashback-scenes. Director Pakula says he had no idea what Streep intended to do with the part until rehearsals began. “She didn’t read with the other actors because she wanted to study Polish before we started filming.” Streep says it took a while before she got to grips with Sophie. “The problem was that Sophie was such a victim. She really let the tanks run over her. Then I saw little bits of me in her. I found she had some spirit, a little backbone. After everything that hits her, she just sort of gets up with a lot of life and vitality. I liked that.”

It is part of Streep’s charm that fame sits lightly on her shoulders. She leads an everyday life full of everyday problems. In New York she rides the subways – “If everybody did, the service would improve”. She does the shopping – “You have to walk half an hour to the grocery store to order deliveries.” She cooks the dinner – “I’m not a good cook and I’m a worse housekeeper. I would duck all that if there was someone else around to do it.” And she takes care of three-year-old Henry Wolfe Gummer, her son by sculptor Don Gummer, whom she married after long-time boyfriend John Cazale died of cancer six years ago. “Henry’s a real nice guy, huge and sassy, a real smart ass. God, he’s so funny. I get so mad and then he says something and it’s so crazy I burst out laughing. He doesn’t take me seriously at all.” Why does Streep, who can obviously afford household help, do most things herself? “I’ve always been afraid to let go”, she explains. “If you lose the understanding of what it is to live day-to-day how can you act anything but movie stars or kings and queens? It’s also a sense of privacy. I just don’t want people around all the time. I like to be with my family. Streep is five months pregnant and taking a year off from work. In a café-au-lait silk blouse, suede vest, skirt and high, flat-heeled boots she looks radiant and full of health; more beautiful, less elegant than she does on screen. Her voice softens as she talks about her private life.

She was with Cazale until the end and the pain of that extraordinary experience is deep in her mind. Her brush with mortiality may explain the sense of urgency that affects all she does. She says she has a short attention span, but that’s too gliv. She hates anything that keeps her in place, prevents her from moving forward. Indecision, wrangling, fame itself can have a limiting effect. They make her impatient. She’s less frenetic now and friends credit her marriage with anchoring her. Gummer, a long-time friend of her brother, has received prestigious awards and commissions in his own distinguished career. But there’s success and success. Streep has made it in a business that, as she says, “we can all agree is overpaid.” Art has a different set of rewards. Does this frustrate her husband? “I would think it would,” she says. “But so far he finds the advantages outweigh the disadvantages. He says that even if I didn’t make movies he would still have the kind of studio he has. And he’s happy about that.”

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|

Posted on November 7th, 2024

|

Posted on November 1st, 2024

|

Posted on October 10th, 2024

|

Posted on September 26th, 2024

|