|

Meryl Streep: I don't want to be a superstar

Woman's Day ·

March 06, 1980

· Written by Diane de Dubovay

|

|

Tags

|

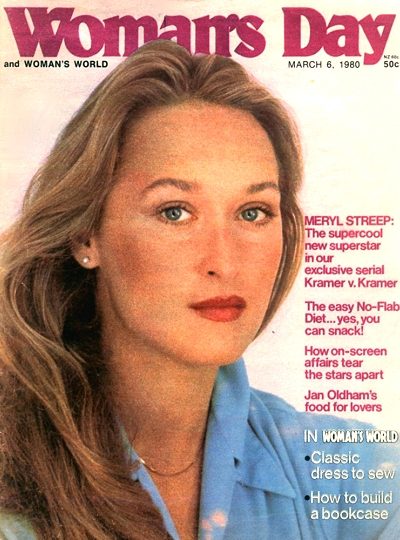

Almost every film she has appeared in has been a blockbuster. Now her latest, “Kramer vs. Kramer”, opens here in March and begins as a serial page on page 43.

Meryl Streep may be the coolest looking actress around, but don’t let that fool you. She is hot. With lightning speed she is emerging as the most riveting and versatile performer of her generation. In quick succession, she has grabbed the plum female roles in a series of box office blockbusters – “The Deerhunter”, for which she won an Academy Award nomination, “Manhattan”, “The Seduction of Joe Tynan”, “Kramer vs. Kramer” and an Emmy Award-winning performance in the TV series, “Holocaust”. Yet so chameleon-like is her acting ability that it is easy for film goers and TV viewers to miss the connection between Meryl Streep in one role and Meryl Streep in another.

Like Katharine Hepburn or Carole Lombard, women who could hurl an expletive or take a though stand without puncturing their patrician images, Meryl is a throwback to what used to be calles “a classy dame.” On screen, her classic features, translucent skin, flowing blond hair and calm blue eyes flicker with intelligence and hidden depths of passion. Along with her cinema contemporaries, Jill Clayburgh and Diane Keaton, she is part of that new breed of classically-trained, frankly smart-as-any-man, New York-based actresses – vulnerable, capable and real – whose career is distinctly non-“Hollywood” and only marginally based on looks. Still, at 30, Meryl seems to have it all. The soft, accessible manner that colleagues and friends alike find irresistible. A multi-media film, television and theater career that has brought her – in just four years – to the treshold of superstardom. A happy marriage to a talented young sculptor. And motherhood – last November – to a healthy boy.

Yet little more than a year ago, when actor John Cazale died of cancer at the age of 42, Meryl suffered such a devastating personal loss that emotinally and creatively, she was brought to her knees. Meryl and John had lived together for two years. An unsund “actor’s actor”, John was best known to the public for his portrayal of Fredo, the wak-willed younger brother in “The Godfather”. The couple met and fell in love while working togehter at a summer Shakespeare Festival in New York’s Central Park. During the last year of his life, John and Meryl worked together in “The Deerhunter”. Then when John became too ill to go out, Meryl gave up working to nurse him around the clock. During the last few weeks, she moved into his hospital room – reading him the sports pages and doing comic impressions of TV newscasts. Although the medical bills, which she quietly paid, kept piling up, with the optimism of a woman in love, Meryl believed that John would recover. Looking back, she remembers that year as “a wonderful time” of intense closeness and communication. But she says, “I was so close that I didn’t notice the deterioration. John’s death came as a shock because I didn’t expect ist.”

Surprisingly, within six months of John’s death, Meryl was married to sculptor Don Gummer in a quiet, backyard ceremony at her parents’ home in Connecticut. For a woman of Meryl’s sensitivity, the question is: How did she manage to get over John’s death and rebuild her life so quickly? “I didn’t get over it,” she replies. “I don’t want to get over it. No matter what you do, the pain is always there in some recess of your mind, and it affects everything that happens afterwards. John’s death is still very much with me. But, just as a child does, I think you can assimilate the pain and go on without making an obsession of it.”

“Maybe it’s a function of expectations delivered by the media. But I don’t think that people in any other century felt they deserved perfection as much as Americans do in the twentieth century. We seem to look at sickness, death, grief or adviserty as somehow being totally unfair. We seem to think, ‘Hey this is not supposed to be happening to me.’ I feel lucky when anything goes right. I feel lucky that I’m not living in Cambodia. I think about it every day.” Possibly because some of the film characters she has played have projected an aloof, somewhat bitchy sophistication, Meryl is often compared to Faye Dunaway. Yet offscreen, this image is instantly dispelled. Lunching with Meryl, at New York City’s Plaza Hotel, there is none of the razzle-dazzle glamour of a movie star. When we speak, she leans forward, looking directly into my eyes. She is kind, considerate, supportive, strong yet gentle, simulating yet easy to be with. She is the kind of woman another woman would enjoy having as a best friend. Fame, however, makes her uncomfortable. Right now, she is at that point where she is stared at and approached, yet the average person is not quite sure who she is. As we eat, a woman accosts her with: “Aren’t you an actress? Didn’t I see you on television… or was it in the movies?” Meryl cringes, but politely explains she was in the TV series “Holocaust”. “Oh, yes,” the woman replies, “Now I remember. I think you’re wonderful.” She is a well-meaning fan, but the interruption is intrusive and intensive.

“Don and I used to love going to museums,” Meryl remarks. “But now we hate them because while we can walk around Manhattan’s Chinatown and the [less fashionable] lower Eastside, where we live, without being recognized, uptown, where everybody’s hip to the latest trends, it’s very difficult. You can’t concentrate on an art object when someone has pushed himself between the object and you and is staring at you, or follows you around whispering your name. If you want to be a superstar, it seems to me you have to hire a press agent and do kinky things to get into the columns. If that’s what it takes, I don’t want to be a superstar. I don’t want to be in the columns. Keeping my privacy is a priority.” When John Cazale died, Meryl went through a thorougly private agony that she has never talked about before. Her seemingly rapid recovery from that tragedy can be attributed to massive work therapy, mountains of support from family and friends, a stoic acceptance of life’s vicissitudes and an instinctive determination to love again – quickly. “Three weeks after John’s death,” Meryl recalls, “a former girl friend of John’s materialized from California and reclaimed our apartment. It turned out that she and John had signed a lease together a few years earlier, but had never lived there together. After John died, my brother, Third [Harry III, two years younger than Meryl, and a dancer/choreographer with his own dance company], moved in with me. Then suddenly when this woman appeared, we had to leave. So within a period of three weeks, I not only lost John but our home.”

Enter Don Gummer. Tall, dark and handsome, at 31, Don, a friend of Meryl’s brother, had been married and divorced from his college sweetheart. At first, Don offered to help Meryl and her brother move their belongings into nearby storage places. But left with excess, he offered to store the remaining articles in his own live-in artist’s studio. Once the moving was completed, Meryl left for Washington and Baltimore on location for “The Seduction of Joe Tynan”. “I did this film on automatic pilot,” she recalls. “But it was probably the best kind of therapy because I worked so hard that there was no time to think of anything else. And at night when we finished shooting, I just collapsed into bed and fell asleep. Another help in getting through that period was working with Alan Alda and the whole film crew, who were amazingly warm and supportive.” When Meryl returned to New York two months later, Don was preparing to leave for a trip around the world and offered his loft to Meryl and her brother as temporary living quarters. Lonely, and touched by Gummer’s kindness, Meryl took the initiative after he left. “I started writing Don while he was away,” she recalls. “He and my brother had been friends for years and I had met Don two or three times, but I honestly didn’t remember him. We really got to know each other through our letters. Then when he returned to New York, he built me a little room of my own in the loft, and told me I could stay. And twenty minuted later we got married! No, actually, it was two months later. It just seemed right. A lot of men had asked me to marry them, but it had never really seemed right before.” And what is Don Gummer like? Meryl sparkls when she speaks of him. “He’s wonderful,” she exclaims. “He’s like me, I mean, he’s very private. And he never says anything he doesn’t mean. He’s warm, strong, gentle, funny, kind, understanding, very creative. I couldn’t live with someone who wasn’t creative.”

Critics have hailed Meryl as the most important actress of her generation, with a range capable of interpreting virtually any kind of role. During her student days at Vassar and Yale (she won a three-year scholarship to the Yale School of Drama and waited tables to pay her expenses), she literally became an acting legend. And today, her peers in the theatrical world revere her talent to the point of treating her like a queen. Say New York’s Public Theater director, Joseph Papp: “Meryl cannot be compared with anyone. She stands very much alone. She is one of those rare actresses who has the capacity to inhabit her characters and make them seem real, not pale imitations, You can see the blood running through her characters.” Yet despite all the lavish praise, there is nothing of the prima donna about Meryl. One finds no signs of battle fatigue. In a profession riddled with competition, jealousy, politics, insecurity and disappointment, she has risen to the top meterorically and emerged seemingly unscathed and with her values intact. “Why do people feel that you have to be neurotic to be an artist?” she asks indignantly. “I don’t understand that concept. I think it’s a very nineteenth century idea. If you feel anxious… if you feel that you’re losing your balance, you stop workinf. It’s as simple as that. I think no matter what you do, whether you’re a housewife or have a career, you have to find a way of opting for a sanity break when you need it. Otherwise, you’ll end up on the psychatrist’s couch.” Recognizing the limtis of her endurance and knowing how to handle stress are safety mechanisms that have helped Meryl stay on an even keel. She has high expectations where her work is concerned. But in terms of her personal life, her expectations are minimal. She makes no demands. She has few preconceived ideals. Instead she tends to accept people and situations as they are, with all their flaws, without criticism and without the slightest feeling of bein shortchanged. It’s a “go with the flow” philosophy.

“My friendships aren’t based on any kind of intellectual stimulus,” she explains. “I don’t seek out my friends, I don’t have any particular standards I expect them to meet, so I’m not easily disappointed. They’re just people with whom I feel comfortable, people who come into my life naturally.” Similarly, the most important men in her life, John Cazale and Don Gummer, were just there. John, considerably older and not nearly as successful as Meryl, was not a particularly “good catch”.” Yet Meryl saw something special in him and made the situation work. In other words, instead of feeling that she is missing something “out there”, she realizes that life is where she is and is frankly grateful for whatever good she finds that comes her way. Another basis of her stability is that unlike the stereotyped ambitious actress who comes to New York to slay the career dragons alone, Meryl was born and raised in New Yersey – just across the George Washington Bridge from Manhattan. New York is her home territory. So there was never that alienating sense of being disconnected from her roots. And every step of the way, she was able to depend on a loving, supporting, close-knit family. “Thank God my family is near, alive and happy,” she says. “I’ve always had lots of supportive people in my live.” Fantasy is mostly confined to Meryl’s work. In her personal life reality, reason and belief in her natural instincts prevail. “I ride the subway a lot,” she says, “and I think all politicians should be forced to ride the subway so that they would be confronted with the reality of life – with the ugliness, with the deprived people who haven’t the strength of the inspiration to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, so simply cannot escape the cycle of poverty and despair into which they are born.”

Despite the democratic personal attitudes, however, Meryl’s professional attitudes are distinctly elitist. From the beginning, she made it clear that she was aiming for the top and had to intention of settling for anything but the best. Asked recently if she had the drive to sustain her career ambitions, she replied, “What I have is more like overdrive.” Where does the desire to succeed begin? Meryl’s ambition grew out of private hell of an unhappy childhood. Though she was raised in a comfortable, loving home, she remembers her growing up years as an agony of feeling ugly and rejected by her younger brothers and classmates. “Nobody liked me,” she recalls with brutal honesty. “I was bossy, prim and determined. I looked middle-aged. The other kids thought I was one of the teachers.” But by the age of 12 she discovered a powerful attention-getting device: She had a beautiful singing voice. And after stunning a school audience with a solo rendition of “O Holy Night,” her parents were convinced that her natural coloratura was worth training. Her mother, a commercial artist working at home, and her father, a pharmaceuticals company executive, took her to New York to study with opera singer Beverly Sills’ voice teacher, Estelle Liebling. Her voice was Meryl’s way of proving she was special. But the voice wasn’t enough. As Meryl says, “There seems to be a crime in this country against not being beautiful.” So after four years, boy-crazy and aching to be admired, she gave up the rigors of voice lessons to concentrate on self-improvement. Molding herself in the image of a “magazine knockout”, she doused her hair with leom juice and peroxide, threw away her braces and corrective glasses… and within a year, transformed herself from a plain, frizzy-haired misfit into a glossily beautiful teenager, who became a high school cheerleader, dated one of the school’s football players, joined the honor society, was named homecoming queen and became the star of the school’s annual muscial productions. Looking back, she says, “It was my first successful characterization.”

Yet instead of feeling popular and accepted, Meryl continued to feel like an outsider. “I thought that if I looked pretty and did all the ‘right things,’ everyone would like me,” she says. “But the other girls were jealous. The program looked too good. I only had two friends in high school and one of them was my cousin, so that didn’t count. Then there’s that whole awful kind of competition based on pubescent rivalry for boys. It made me terribly unhappy. My biggest decision every day used to be what clothes I should wear to school. It was ridiculous. When I got to Vassar, my life changed because met the most wonderful women. So, suddenly I feld accepted by the entire other half of the human race. From the time I entered college until now, I’ve never felt the need to compete with anyone. That just all went out the window. At Vassar it was commonplace to give your best shot, so that became a habit. I learned to believe in myself. I acquired a genuine sense of identity.” Since her marriage, Meryl has temporarily shelved er hot-as-a-pistol career in favor of nesting and domesticity devoting herself to marriage and motherhood. On an average non-filming day, Meryl likes to putter around the house, sifting through an avalance of scripts submitted as possible projects, and reveling in the 24-hours-a-day companionship of her husband, who works on his large, wood and stone abstract sculptures at home. Noticeably absent from the trendy New York restaurant-and-party-scene, Meryl and Don are determined to keep the pattern of their lives simple and unpretentious. “During the day, when I’m not working. I like to walk for an hour or two,” says Meryl, “just for air and exercise. Or maybe I’ll buy something momentous, like one light bulb for the loft.” The couple also enjoys visiting art galleries, reading, listening to music of having friends over for dinner. “My work has been very important,” says Meryl, “because if you want a career, I feel that you have to build a foundation in your twenties. But we wanted to have a child because we felt that not enough people in our circle of friends were having children. Friends of mine from college, who are very accomplished, are delaying children until they are older because of their careers. Streep’s baby, named Henry IV after Meryl’s father and her brother, arrived three weeks late and, because it would have been a breech birth, was delivered by Cesarean section. “There was nothing to it,” Meryl enthused afterwards. “Don was wtih me and held the baby right after it was born. It seemed the most natural thing in the world.”

Immersed in motherhood since the baby’s birth, Meryl has been known to break off a photo-session to breast-feed Henry or to interrupt an interview to change his diapers. So far, Meryl has taken care of the baby herself. Don plans to be a modern, actively involved father, but preparation of his one-man exhibits clearly takes precedence over full-time baby-sitting chores. Currently Meryl is searching for a part-time nanny, “someone to help out once or two afternoons a week so that I can go out.” And this spring, when she goes on location in England for “The French Lieutenant’s Woman”, she expects to take the baby and a personally-trained nanny along with her. Don will visit as often as his work permits. “When you’re single, you usually don’t think more than twenty minutes ahead,” Meryl observes. “But after you are married, you suddenly start thinking twenty years ahead. This child will have to get us into the next century. His generation will have to hdeal with problems of survival that our generation never even thought of: pollution, depletion of natural resources, population control…” Does she plan to have more children? “I want to see how this one turns out first,” Meryl replies cautiously. Recently, Meryl and Don purchased a 96-acre country retreat in upstate New Sork. “We mortgaged ourselves for a million years,” she says. “We bought a Christmas tree farm with a fully furnished three-room house. It’s like having a tiny apartment in the midst of a vast frontier, but it’s part of our dream ob becoming independent of the utility companies. We plan to install a windmill and a solar system. We also have five thousand Christmas trees. No, we’re not thinking of going into the Christmas tree business,” she laughs. “But it’s wooded and quiet, and it’s one of the precautions we’re taking to safeguard our privacy.” Already she has lined up work that will carry her through the next two years. Among the future projects are leading roles in “The French Lieutenant’s Woman”, which Harold Pinter is adapting for the screen, and “Sophie’s Choice”, based on the bestselling book by William Styron and directed by Alan Pakula. Despite the success of her career, it is obvious that Meryl’s husband and child now have become the focus of her life and everything else is peripheral. If she felt the demands of her career were conflicting with her personal life, one wonders if she would consider giving up the career? “I don’t think that will be necessary,” she replies. “But yes, of course, I don’t think that any enterprise is bigger than your life’s needs or your humanity.” And what of her quest for privacy? “You can’t just hide out in the unfashionable parts of the city or escape into the wilderness of upstate New York all the time, can you?” “Oh yes I can,” she retorts with characteristic optimism and determination. “Just wait and see!”

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|

Posted on November 7th, 2024

|

Posted on November 1st, 2024

|

Posted on October 10th, 2024

|

Posted on September 26th, 2024

|