|

A Mother Finds Herself

Time Magazine ·

December 03, 1979

· Written by Pad Gray

|

Meryl Streep could, obviously have made it, to the screen on looks alone. Says Director Michael Cimino, who worked with her on The Deer Hunter: “The camera embraces her.” Lucky camera. Many women would kill for her slender, fashion-model figure, for that ash-blond hair, oval face, porcelain skin and those high, exquisite cheekbones. Her eyes mirror intelligence; their pale blue sparkle demands a new adjective: merulean. Only a slight bump down the plane of her long, patrician nose redeems her profile from perfection.

Yet she is more than just another gorgeous face. The typical Hollywood starlet may think that August Strindberg is a hot new agent, but Streep played Miss Julie at Vassar. Beginning her professional stage career in New York only four years ago, she conquered prized roles in Shakespeare (Measure for Measure, Henry V, The Taming of the Shrew), Chekhov (The Cherry Orchard) and Brecht-Weill (Happy End), as well as in works by Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams. This repertory training came to Meryl because she was ready for it; her education went on in public, but critics and audiences did the learning. Director Arvin Brown expresses what threatens to become a brodmide when he calls her “the most talented actress of her generation.”

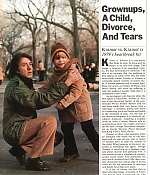

Despite her theatrical training, there is nothing stagy about Streep’s performance in Kramer vs. Kramer. Emotions play across her face as subtly as breezes ruffling pond; rarely have the varieties of anguish and uncertainty been so thoroughly catalogued through look and gesture Streep’s understated suffering rescues the character of Joanna Kramer virtually no-win plot: bad enough that a mother should leave her young child and then disappear from the film for nearly an hour; worse still that she come back and try to break up the new that her husband and son have painfully built. If Joanna is a villain,” Streep recently told Times’ Elaine Dutka, “if there’s a white hat-black hat situation, that doesn’t make for an interesting courtroom scene, which I consider the climax of the film.” Joanna’s testimony at the custody hearing is indeed one of the film’s most wrenching sequences, precisely because Streep avoids histrionics, lowering her voice rather than raising it. When she cries she does so visibly in spite of herself. So thoroughly had Meryl come to inhabit her character that she wrote every word of this speech herself.

Director Robert Renton recalls her work that day on the set with amazement: “We must have shot that scene from seven in, the morning until six at night, over And over again. First in close-up, then a Clowning as Kate In Taming of the Shrew medium shot, finally a long one. Later in the day, we shot only Dustin reacting to her on the stand. During this last take, all 30 people in the room were facing Dustin. I happened to be watching Meryl, as well. She had the same intensity as she had when she first did the scene.”

Added to this consistency is her instinct for the impromptu, for the movement or gesture that no one thinks of until she does it and makes it inevitable. Her role in The Seduction of Joe Tynan as the other woman, having an affair with a married U.S. Senator, also placed her in ar uneven struggle for audience sympathy. Many would argue that Meryl won hands down. Recalls co-star Alan Alda: “When she blew Tynan a kiss at the airport after their affair, that was Meryl’s own inspiration. It was her way of conveying that she didn’t get what she wanted. but she was taking life on her own terms.”

Life has rarely failed to give Meryl, who is 30, what she wants. “Mine is a Cinderella story all right,” she says with a trace of self-mockery. She and her two younger brothers grew up in the leafy and comfortable suburbs of central New Jersey. Her father was a pharmaceutical company executive and her mother a graphic artist who did most of her work at home. “I didn’t have what you’d call a happy childhood,” insists Streep. “For one thing. I thought no one liked me. Actually, I’d say I had pretty good evidence. The kids would chase me up into a tree and hit my legs with sticks until they bled. Besides that, I was ugly. With my glasses and permanented hair, I looked like a mini-adult. I had the same face I have today, and let me tell you the effect wasn’t cute or endearing.” Brother Harry, two years her junior, agrees: “in fact, she was pretty ghastly when she was young,”

The prettiest thing about Meryl in those day was her singing voice. A promising coloratura soprano, she began taking lessons in New York with voice coach Estelle Liebling. “The first opera I went to” recalls Meryl, “was Douglas Moore’s The Wings of the Dove, with Beverly Sills. It was incredible to see her onstage. Until then, I thought she was just a nice lady wh had the lesson before me.” One morning Meryl got up, squashed her glasses underfoot, put peroxide and lemon juice on her hair and set out to be “the perfect Seventeen magazine knockout.” Boys quickly appeared, and so did a high school teacher determined to build musicals around Meryl’s singing. During her freshman year she made her first appearance onstage as Marian in The Music Man. The young performer was talented but hardly driven. She gave up voice lessons when they interfered with her duties as a cheerleader. Classmates name her Homecoming Queen.

Next came Vassar and the recognition that this wholesome young woman possessed an eerie gift. Clinton Atkinson, a director on the college staff, found her acting “hair raising and absolutely mind boggling. I don’t think anyone ever taught Meryl acting; she really taught herself.” After graduating with a major in drama, she joined a small repertory company in Vermont and then won a three-year scholarship to the Yale School of Drama. Her classvvork won ever higher praise. “Whenever, she did a scene,” says Director Robert Lewis, who was a professor there at the tithe, “You wished that the author was there to see it.” She was also much in demand for major roles by the Yale Repertory Theater. By the time she earned her master of fine arts degree she had developed an incipient ulcer: “It was very liberating when I got out to find that you’re not competing with 24 people but with 20,00 others.”

Meryl had auditioned in New York occasionally while still at Yale. When shw moved to the city, directors scrambled to use her. Her first professional appearance was at Lincoln Center in Joseph Papp production of Trelawney of the Wells. Next she played in a program of two one-act plays and did the seemingly impossible: she became both a slovenly, bovine Southerner in Tennessee Williams’ Twenty Seven Wagons Full of Cotton and a thin, sexy secretary in Arthur Miller’s a Memory of Two Mondays. Says Director Marvin Brown: The audiences didn’t realize that they had seen the same girl twice. These were the first of seven stage roles that Meryl was to play in 1976.

During one, a Central Park production of Measure for Measure, she worked with John Cazale, a respected actor known to film audiences for his role as the cowardly son Fredo in the Godfather and the Godfather Part II. They fell in love and began living together. Actor Joe Grifasi, a friend of both a the time, says: “Meryl admired his ability to cut through the crap and focus on the essentials. He was very careful to maintain his equilibrium.” They spent as much time together as their careers permitted; the summer of 1977 found them in Steubenville, Ohio, working on The Deer Hunter. Neither one talked n the set about what they both knew by then: Cazale had bone cancer and, barring a miracle, was dying.

Meryl next went to Austria to work on the TV series Holocaust. Cazale was too weak to follow her. “I wanted t go home, she say. “John was very sick and I wanted to be with him. But they just kept extending the damn thing. It was like being in prison for 21/2 months.” Actor Fritz Weaver shared this internment and remembers Meryl admiringly: “In Holocaust she played a woman whose lover was imprisoned in a concentration camp. Meryl must have been living it twice, in the story and in real life. But there was not one moment of self-pity.”

Rushing back to New York, Meryl took a leave from acting to care for Cazale full time. During his last few weeks she moved into the hospital; every day she read him the sports pages, comically imitating the overheated delivery to the TV announcers and trying to nourish his spirits until the end. He died in Mary 1978. Afterward, says Streep, “I was emotionally blitzed.” She began work on Joe Tynan four months later: “It was a selfish period, a period of healing for me, of trying to incorporate what had happened into my life. I wanted to find a place where I could carry it forever and still function. I’m O.K. now, obviously, but the death is still very much with me.”

Along with her work , Meryl found comfort in the companionship of Sculptor Don Gummer, a longtime pal of her brother Harry’s. Before some friends even knew they were seriously involved, they married in September 1978. Stage and film work kept Meryl on the run during her first months of marriage; since April, though, she has been staying home, where her husband works, in a sprawling studio loft south of Greenwich Village. For fun they visit galleries and museums, go to the movies and entertain friends at home.

Meryl’s pregnancy was the prime reason for her professional inactivity. On Nov. 13, she gave birth to a 6-lb. 14-oz. boy, named Henry. The baby will impose some new demands on the haphazard, casual Gummer household; Meryl’s recorded message on her phone-answering machine sounds more laid back than most new parents are allowed to be: “Hello … um … if you want to leave a message, please wait for the beep because … um … I don’t know… otherwise the thing cuts off. Thank you.” There is no sign of the actress in this voice, but it reveals a side of Meryl that her friends know well. She ducks formality whenever she can and prefers rolled up jeans and canvas shoes to the sleek clothes she wears in Kramer. Sensitive to a variety of women’s issues, she speaks forcefully about sexism in films and the need for new methods of male contraception.

Moviegoers have yet to see the full range of Streep’s art. She is an expert mimic (she copied her dead-on Southern accent in Joe Tynan from Dinah Shore) and can turn a hilarious pratfall. Her film roles have mainly been those of vulnerable modem women. She has not yet played a period character from a position (if strength, but plans to start work on the screen version of John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman early next spring.

The prospect of Meryl as an enigmatic Victorian rebel is intriguing. “Eventually,” she says, “I’d like to be as adventurous in films as I’ve been onstage. I know you’re supposed to do film small, but I think I hold back too much.” When she lets go, everyone had better watch: “There’s so much untapped with in me.”