|

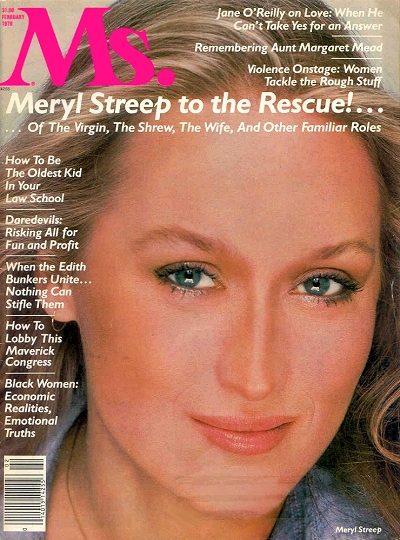

Meryl Streep to the Rescue

Ms. Magazine ·

February 1979

· Written by Susan Dworkin

|

|

Tags

|

Cheekbones is a funny thing. High cheekbones say “class”. Prominent cheekbones say “patrician”. When you’re homecoming queen at your high school in New Jersey and you’ve got great cheekbones, people think you’re destined to be a model of high fashion. If you decide to be an actress, people think you’re destined to play Ophelia. But Meryl Streep didn’t want to play Ophelia. She wanted to play everybody. When I meet her, she is surrounded by press agents. She shows me a large glass block she has just received, inscribed with the gratitude of the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, awarded for her portrayal of the courageous German daughter-in-law in NBC’s mini-series, “Holocaust”. Her golden hair is piled up neatly. Her crystal blue eyes are serene. Her voice is soft. At 29, she looks like a delicate, tapered candle. Later on, the press agents are gone and we sit on the floor, drinking wine and eating sandwiches. Her hair falls apart; she becomes less “beautiful” and more fascinating. Her eyes explode. Her face boils over. She tells me stories about her life in the theater and she plays everybody. With a voice as malleable as Play-Doh, she imitates characters – both real and fictional – and I crack up. Thus did comedy save at least one gorgeous woman from trivialization – for comedy is based on self-examination and a keen appreciation of the world’s madness and the joy of being laughed at. As long as you get a kick out of being laughed at, you can’t be destoyed by your cheekbones.

“Meryl has done what we all want to do,” says one actor who knows her. “She made it, very big, very fast.” In four years since Streep was graduated from prestigious Yale Drama School, she has participated in a continual series of dramatic events that absolutely defy the notion that young actors must starve to succeed. “Ah, you were in ‘Trelawny of the Wells,” a director remarks to an actor auditioning for him. “Then you must have been there when Meryl Streep first appeared on the New York stage and the world came to a halt.” They laugh – not at Meryl but at the crazy business of the theater, in which the world still stops dead for talent. In 1975, she played a fading ingenue who had just stumbled into becoming the manager of a theatrical company in “Trelawny of the Wells”, and delighted the small – but poweful – Public Theater audiences in New York. People in the business began to talk about her. She spent part of a summer at the O’Neill Playwright’s Conference, an annual tryout of new plays on the murky coastal bogs of Connecticut – the place where Eugene O’Neill spent his beclouded youth. (“No wonder his mother became a junkie,” mused one grayed-out author.) People in the business come from all over to the O’Neill to shop for next fall’s great works. People in the business saw Meryl Streep at the O’Neill and she became the great new work of the 1976 season. No sooner was she finished with “Trelawny” than the Phoenix Theater engaged her to appear in an evening of two classic one-act-plays – “Twenty Seven Wagons Full of Cotton” by Tennessee Williams and “A Memory of Two Mondays” by Arthur Miller. “It was a great showcase for an actress,” she says. “In one play, I was very fat; I had all kinds of padding and prosthetic breasts. In the other, I was a completely different person. What the people saw fed into what I wanted for myself – which was not to be typed. On Christmas Eve, Joe Papp called me and asked if I would play Isabella in “Measure for Measure” at the New York Shakespeare Festival in Central Park.”

On “Measure for Measure”, she met and fell in love with John Cazale, the brilliant actor who had made such an impact as the weak and dissolute brother of Al Pacino and James Caan in “The Godfather”. “It was a magnificent affair,” recalls one of their colleagues. “Golden.” Meryl was golden. She appeared in Chekov’s “The Cherry Orchard”; she replaced Shirley Knight as the lead in Brecht’s “Happy End”. Television began to happen to her. In “The Deadliest Season”, the story of a hockey player who accidentally kills someone in the course of that horrendous, violent game, she played opposite Michael Moriarty. They would share the screen again, in another Herbert Brodkin production, “Holocaust”. In “Holocaust”, everybody saw Meryl Streep. She won an Emmy for it, but didn’t pick it up. (“I don’t believe performances should be taken out of context and put up against each other for awards.”) Along with one eldery priest who died in Dachau, she played the only German worth redeeming in that litany of torture and shame. And everybody loved her. Meryl did not love “Holocaust”. “Austria was unrelentingly Austrian. The material was unrelentingly noble. Matthausen was too much for me. Around the corner there was a Hofbrau, and when the old soldiers got drunk enough, and it was late enough, they would pull out their souveniers of the war, it was very weird and kinky. I was going crazy – and John was sick and I wanted to be with him.” Back in New York, John Cazale was sick of bone cancer. By the time Meryl got home, he was dying. They were together as much as possible during the last weeks of his life. After he died, she went right to work in the soon-to-be-released film “The Senator” with Alan Alda. “I did this film on automatic pilot,” Meryl remembers, “I couldn’t have worked with a more lovely, more understanding person than Alan Alda”. I suggest that perhaps her work has been a comfort. She shook her head. “For some things, there is no comfort.”

Meryl Streep goes for an interview at the hotel suite/headquarters of Stanley Jaffee. He is producing the film version of “Kramer versus Kramer”, the antifeminist backlash novel about a woman who leaves her husband and her little boy because she can’t cope with her career and her kid too. Stanley Jaffee and Robert Benton, the director/screenwriter, and Dustin Hoffman, the star, ask her what she thinks of the story. Well, she says – making herself very comfortable – this is what is wrong with the story. The woman is too evil. Her conflicts are too narrowly described. She’s a reflection of a real struggle that is going on in this country, but she doesn’t refelct it sympathetically. We should really understand why she leaves. We should really sympathize when she decides to come back and regain custody of her son. And when she decides to give up the boy to his father in the end, it should be for the boy’s sake, not her own. That’s more realistic. Benton, Jaffe, and Hoffman listened. They are themselves disturbed by the woman-hating element in the book’s success; they rewrite their script and cast Meryl Streep as the female lead. What if they hadn’t changed the script? Horror flares in her candle face. “They couldn’t not have changed the script! I mean, I couldn’t have been interested in the role if they hadn’t changed the script!” I’m not so sure if what Streep said is strictly true. The way she researches a role and prepares her part, I think she could find a way to live with her principles, to be a person she wants to be, even when she can’t change the script. Preparing to play the troubled Mrs. Kramer, she first talked to her mother, who told her, “All my friends at one point or another wanted to throw up their hands and leave and see if there was another way of doing their lives.” Then, Meryl Streep hung out on the Upper East Side where the Kramers lived; she read the magazines that the woman she was playing would read. “Every moth, they carried the same story. ‘Judge Mary So-and_so, brilliant jurist and mother of five, handles her career and this amazing household, together, teriffic! Everything this woman reads tells her that she must be able to do both! But what if you can’t do both? What if you just can’t handle it? What if you can’t understand why the world won’t allow you to do one or the other?” For a few seconds, Streep’s voice changes; her face reddens; she is playing Mrs. Kramer, just by talking about her.

At Yale, Meryl Streep learned how to use her body as “an instrument”, to make funny sounds in front of mirrors to train her voice, to unlearn her regional accent so she could play anyone in any play, and to “treat the text as the Bible.” But for television and films, an actor may have to unlearn it all. Because now the text is almost meaningless, spun out by not just one but numbers of writers; now there’s a little screen that negates the sweeping gesture; and amplified sound systems that hates a booming voice. Now that Meryl Streep is making movies, she’s adapting. She is learning to “defend” (her word) characters who don’t have great lines – in scripts that are essentially soundtracks. Meryl Streep is currently defending a girl named Linda in “The Deer Hunter”. Linda works in a grocery; she’s pretty and sweet – the virginal “girl back home” – for both Robert De Niro and his best friend, Christopher Walken, while they drown in the blood and insanity of Vietnam. “I was exstatic to be in I was ecstatic to be in ‘The Deer Hunter’ because I was living with John Cazale at the time and we could be in it together. That is so hard for actors, you’re always in different cities, missing each other… They needed a girl between the two guys, and I was it.” Having seen “The Deer Hunter”, a three-hour epic about men and their bonds and war and the blood that comes out of people when they are shot, you could sympathize with Streep’s problem. She rolls her eyes and croaks when she recalls the challenge of portraying Linda in this male landscape. “I though to myself: Oh, boyyyy, how am I gonna stand up for this character? I thought of all the girls in my high school who waited for things to happen to them. Linda waits for a man to come and take care of her. If not this man, then another man: she waits for a man to make her life happen.” That was the reality that Streep found for Linda, and it works. When her boyfriend’s best friend flirts with her, she’s embarrassed, she doesn’t know where to put her eyes. She shoves and pushes to catch the bridal bouquet at a Russian-American babble of a wonderful wedding that goes on too long and she does, she cries tears of happiness. When the “Welcome Home from Vietnam” party doesn’t work out (the returning De Niro orders his taxi to take him to a motel instead), she sits alone among the flowers and pulls her blue sweater around her like an old old lady. When De Niro surprises her the next day – he has really come home to her – they walk through the little town and she holds his arm to tightly and so proudly that you feel she has been rescued from war. She is the girl who waits for someone to give herself to, for anyone who will save her from the back room of that grocery.

If Streep had little script to fall back on in “The Deer Hunter”, she faced quite the opposite challenge as Kate in “The Taming of the Shrew”. According to Shakespeare’s script, Kate is beaten and starved and ridiculed into submission by an unyielding, macho gold differ. In the end, she tells her sister and her friends: “Such duty as the subject owes the prince, Even such a woman oweth to her husband, And when she is forward, peevish, sullen, sour, And not obedient to his honest will, What is she but a foul contending rebel, And graceless traitor to her loving lord?” Go “defent” that in the summer of 1978 in Central Park in New York City! So Streep played a Kate in love, a Kate who is taught by Petruchio “to channel her passion into something that makes sense instead of having it always spray out all over the place as anger.” Raul Julia played Petruchio as a giant of sexuality, a man so powerfully attracted to Kate that everything he did to her was for her own – their own – good. Streep’s Kate is a woman who finds, not humiliation at the hands of her husband, but reason in the arms of her lover. At the end of the play, she bends down to “place her hand below her husband’s foot” and he, to show that this was no taming but a declaration of love, gets down on his knees and kisses her hand.

There are no facts to suggest that Meryl Streep is a born actor. Her father, now retired, was an executive with a pharmaceutical company. Her mother had her own graphic business, at home. No one in the family was a performer, though one of her two brothers is now a modern dancer. The whole career comes out of her personality, and the willingness of her family to support her, in whatever she wanted to do. “I wasn’t an exceptional student,” she says. “I always got one C”. That was in the class in which she didn’t like the teacher. “If I didn’t like the teacher, I would cut up in class and get a C. My favorite part of high school was the boys who sat in the back row. They were so funny! So much of what I know about comedy – event the most sophisticated comedy – comes from high school, because it’s such a painful, funny time. And some of those boys in the back row, who now sell real estate in New Yersey, were the most brilliantly funny people in the whole world. I was a very good audience before I ever thought of being a performer.” She was on the swim team. She became a cheerleader. She became homecoming queen. She had a prodigious soprano so she starred in all the school musicals. She went to Vassar. She might have gone to Bennington if the interview had taken a different turn. “This woman interviewed me,” Streep recalls. “She said, ‘Ahhhhh, what books have you read over the summer?! I looked at her. I said, ‘What do you mean, books over the summer?!’ I had read none. I was on the swim team. ‘Do you mean,’ she said, ‘that you haven’t read any books over the summer?’ I thought, oh, yeah, I did go down to the library one day because it was raining and picked up this book and read it cover to cover, it was called Dreams. I thought it was fascinating, so I told her all about it. She asked who had written it. I said, ‘Carl Jung.’ (J like in jugular). She said, ‘Please, Jung.’ (J like in Youngstown.) I said, ‘Daddy, take me home.’ I mean that was the biggest book that anybody ever read over any summer, and she’s yelling at me because I don’t say the name right!”

When I ask her how she liked Vassar, Streep answers, “It was great being with all those women.” Why? I wonder, and she does a take on me, and shouts: “Because I had been homecoming queen! I had come from this socially cut-throat, huge, coeducational high school, where if your wore the wrong shoes or showed up with the wring guy at the dance, you were finished. But at Vassar – for those few years at least during the week [she armended, laughing] – it wasn’t true. I remember feeling: I can have a thought. I can say ‘asshole’. I can do anything, because everything is allowed. Oh, it was a great relief.” At Vassar, she had a class called Introduction to Drama. She got up one day and “did” Blanche Du Bois, and her teacher, Clint Atkinson, came running over to her, hollering: ‘You’re good! You’re good! Read Miss Julie.” That was written by a man who really had a grudge against women,” I say. “I didn’t care what it was about! All I knew was that I got to take this ax and cut off the head of this canary, and my friends in the second row would be screaming, Ooooooh! Arrggghhh! I loved it!”. She finished school and did a season of plays with a little-theater company in Woodstock, Vermont. “I made forty-eight dollars a week and lived in this beautiful house – which I surely couldn’t afford to live in now – donated to us by a wonderful old lady who liked to support artists. We did tiny little three-character plays. I directed some. I sold ads for some. I knew then that something was being born. In each little role that I did in fron of a ski audience, I gave more of my attention to it, and I had always been kind of scattered, so that was an event. I knew that it was not enough to be an actress in the snows of Vermont. I knew that if I was deciding to do this thing, I ought to do it right.” So she applied to Yale Drama School. “As soon as I got into Yale, there was no turning back.” Meryl Streep got an ulcer at Yale. From what? “The TENSION!” she booms, in a voice like the voice that says “Italian” in the Aunt Millie’s tomato-sauce commercial. “Every year, there would be a coup d’etat. The new guy would come in with all the new people and say, whatever you learned last year, don’t worry about it. This is going to be a completely new approach.” She did 12 to 15 roles every year – “twelve to fifteen people that I really crawled inside of” – and she competed with the same nine actors the whole time. Asi twould be with the Emmys, she couldn’t cope with the notion of actors being “up against each other.”

“I would go and say, ‘I can’t do it any more, I’m going to throw up from the pressure! And of course, they would say to me [light, mild voice, imitating her teachers there], ‘Pressure? What pressure? You think this is bad, wait until you get out of here, will you have problems?’ The minute I got out there,” Meryl Streep says, “I didn’t have any problems.” What do you do after you go to graduate school? You look for a job in your chosen field. But there are, according to all sources, very very few jobs for actors, even well-trained ones with ulcers. So you go to a mass audition, run by an outfit called Theater Communications Group, which tries to be of service to theaters, particularly regional theaters outside New York, and you hope that some theater will hire you. All the graduates of drama schools go there. “We had a class on how to audition for TCG. It was unbeliveable. Everybody had their two pieces ready – the serious one [Streep’s voice descends the scale] – and the comic one [her voice ascends]. The Shakespeare – and the modern. I stayed overnight in New York on the day before the audition. The next morning I woke up, looked at the clock, and went back to sleep. I didn’t go.” She launches into imitation, á la Laraine Newman, mouth hanging open, eyes glassy: “Ooooh, for gawd’s sakes, where’s Meryl?! Ohhhhh, for gawd’s sakes, she’s really fucked herself now… Oh, man, you know… she is fucked!’ I thought: now you’ve done it. It’s all over. You’re finished. In fact, I think Meryl Streep knew someplace down deep in her soul that she really wasn’t finished, that in fact she might have been a lot more “finished” if she had secured through the TCG audition a steady hob at a small regional theater and had spent a good many days working her way back to New York. Instead, she went to Rosemarie Tichler of the Public Theater. “I begged her to give me an audition. She asked why I wasn’t at the TCG audition. I told her I having stomach trouble. She said, ‘Well, all right’ And she saw me. And she said, ‘I may have something for you. And that’s how I got the part of the manager in ‘Trelawny of the Wells’.”

A few months ago, Meryl Streep married Don Gummer, a sculptor. She is a little concerned toward the end of our interview that he may not have found the dinner she prepared. She calls him. He has found it, fine. “He’s very independent and self-sufficient,” she says, beaming like a candle again. “I feel like I have been visited by this angelic force.” It is late; we say good-bye to each other and shake hands and she goes home to her husband. I think about what she has said to me, this rising start, this consummate play of other people: “Success doesn’t feel like success. I apply myself to each job with the same commitment, I’m doing the same intensity of work I did at Yale or in that little theater in Vermont. I would like to have a certain amount of autonomy. I admire Jane Fonda. But I also don’t want to spend all my time immersing myself… in the business of myself…”

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|

Posted on November 7th, 2024

|

Posted on November 1st, 2024

|

Posted on October 10th, 2024

|

Posted on September 26th, 2024

|