Simply Streep is your premiere source on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her three Academy Awards and

the praise to be one of the world's greatest working actresses. Created in 1999, we have built an extensive collection to discover Miss Streep's work through an

archive of press articles, photos and videos. Enjoy your stay and check back soon. |

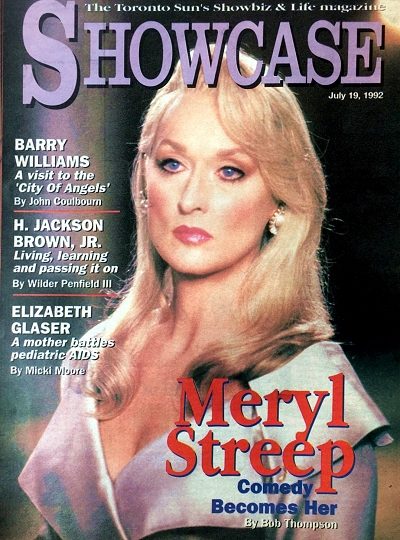

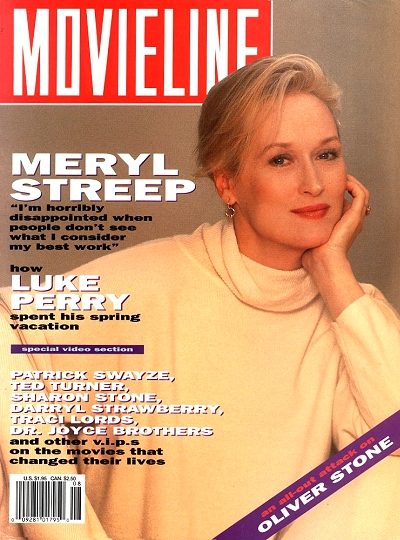

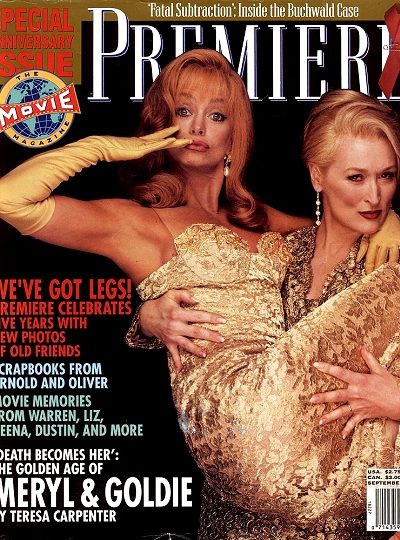

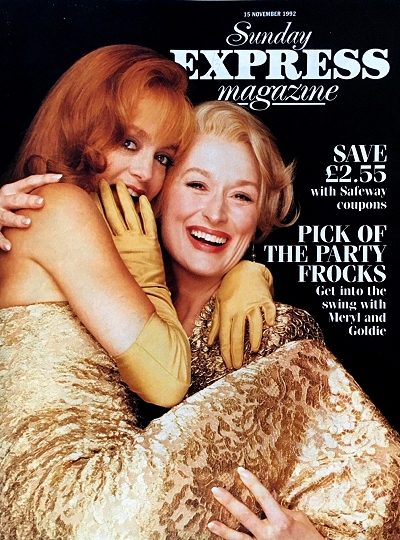

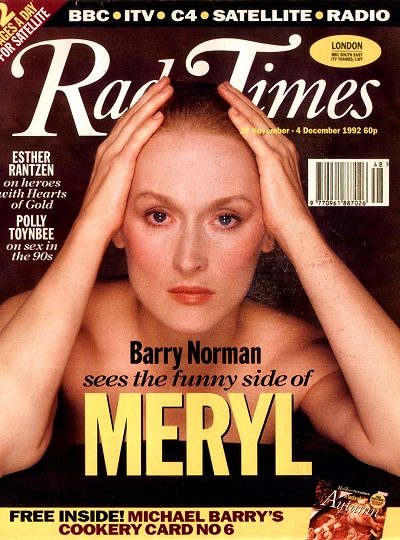

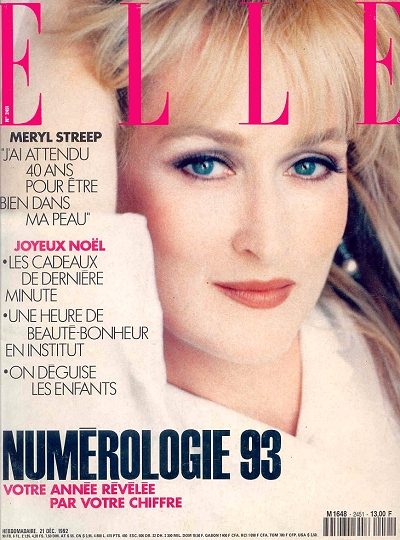

As if it wasn’t difficult enough to find a good leading role on film in the early 1990s, Meryl Streep teamed up with Goldie Hawn to find a project with two female leads. The actresses turned friends wanted to share their star power on the screen togehter, and although they were turned down by Hollywood at first, they found their match in Robert Zemeckis’ turn on the night of the living dead in Los Angeles – women who want to stay young forever. What a stretch for Hollywood.

Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn are probably friendship-goals in life and on film, but they couldn’t have approached their careers more differently. Hawn rose to fame in the late-60s playing dumb blonde characters in a string of more and less successful tv shows features – even winning an Academy Award as Best Supporting Actress in “The Cactus Flower”. But the actress wanted more – better roles, and more power. She founded her own production company, The Hawn/Sylbert Movie Company, with Anthea Sylbert in the late 1970’s and started producing starring roles for herself. They struck gold with their first producing effort – a starring role in “Private Benjamin”, which became a box office hit and a critical darling. Hawn/Sylbert continued to produce more starring roles in “Protocol”, “The Late Shift”, “Criss Cross” and “Overboard”, among others. Although Hawn actress semi-retired in the early 2000s and only shows up on film every once in a while (decade), she has paved the way for many actresses to come. On the other hand, Meryl Streep has never shown interest in any other part of the business than acting. When aksed by Simply Living in 1991 about building her own production company, she said, “I don’t want to start a company. I have lot of other concerns. All I am is an actress. That’s all I wanted to be, ever. I don’t want to be on the phone, talking to unions about set-ups, lunches, how to move trucks off the freeway, overtime. I have no interest in that.”

Hawn and Streep joined forces in the early 1990s and started looking for a project to work on – one with two strong female characters. Finding such a premise was as difficult back then as it is today, but they did find an option with the script of “Thelma and Louise”. The roadmovie drama about two women on the run was sought-after by many actresses – when it was treated as a small independent project, the first choices were Holly Hunter and Frances McDormand. But as soon as the project provided more mainstream appeal, every actress in Hollywood wanted to play either one of the parts. Hawn and Streep were two of them. They invited themselves to Pathé to pitch themselves for the film. They didn’t have their agents make the call, they did it themselves. “To sit in a meeting with Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn was spectacular,” remembered casting director Becky Pollack (daughter of Sydney). “They were enthusiastic and adorable and smart.” The discussion was vigorous, especially when it came to the ending, which gave the stars some trepidation. They didn’t lobby to change it, necessarily, but they toyed with alternatives, like an escape to Mexico, for instance. Streep suggested it might work if her character, Louise, pushed Thelma out of the car at the last moment, saving at least the life of the one friend who hadn’t committed murder. In the book “Off the Cliff”, chairman Alan Ladd Jr. was smitten and eager to capitalize on the oomph of such A-plus-plus-list stars. “I think that Meryl could do anything,” he says. As for Goldie, he was concerned the audience would come in with false expectations of lighter material, but still he suggested them for a meeting with Ridley Scott. In the end, their casting fell through – not because of creative differences, but because Pathé wasn’t willing to pay their salary demands.

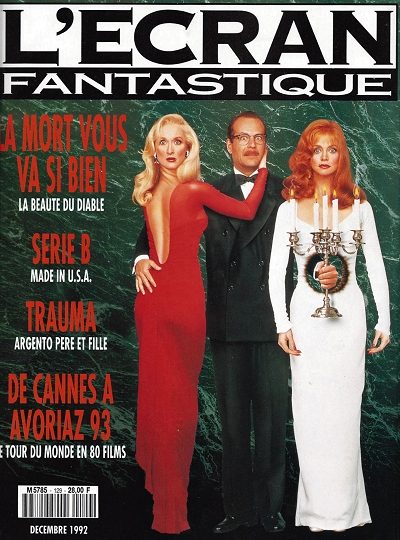

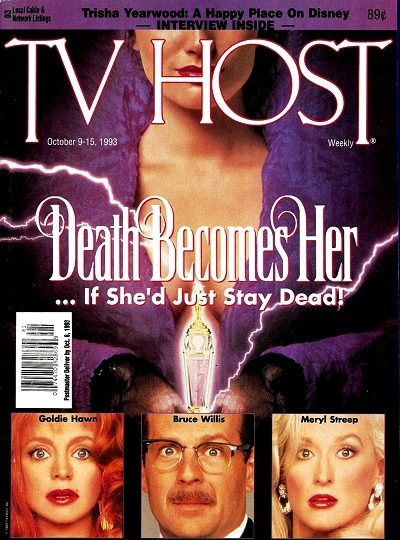

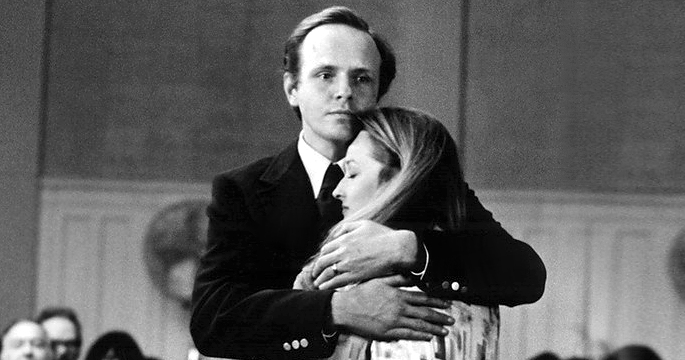

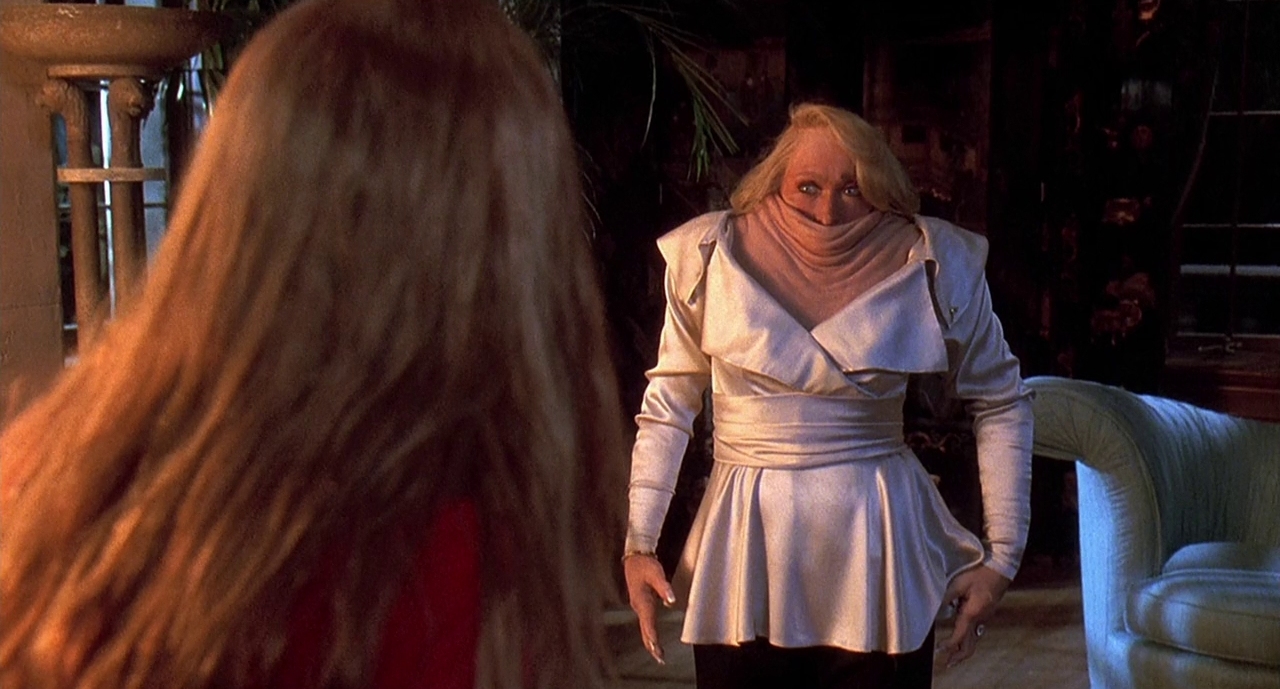

By the end of 1991, they found a project that would offer two strong female leads. After bringing Hollywood’s special effects to a whole new level with “Back to the Future” and “Who’s Framing Roger Rabbit?”, director Robert Zemeckis was eager to go the extra mile and decided on “Death Becomes Her”, the story of two rivaling women – a famous author and a has-been actress – who only have two concerns in life: Who looks younger and who’s getting the man! The cartoonish character profiles surely rang true to Streep, having lived in Los Angeles for two years by now. She told Simply Living in 1991: “It’s an alien culture for someone from Connecticut. They way people are. The way your money and your position in show business define where you are in the town. And how you look is so important. This fear of aging here – it’s pervasive. Even though they fix it – they inject it, lift it, but they don’t fix the hands, or the mind. It’s a sad town for older women. And, of course, what kind of car you drive, is actually an issue here. It’s amazing”. Her quote, given a year before she joined “Death Becomes Her”, is a fairly accurate description of her character, Madeline Ahston. A movie star in the 1970s, her best times are long behind her. She finds joy in meeting her high school frenemy Helen Sharp – because she’s dowdy and looks older than her – and, even better, Madeline hits the road with Helen’s fiancee and marries him. A decade later, the tables have turned. Madeline and Earnest live in an unhappy, alcohol-fueled marriage while Helen has thrived and emerged as a best selling author, looking ravishing. Madeline finally discovers Helen’s secret – a magic potion being sold to wealthy Los Angeles socialites that makes them look young forever. The only side effect it has, is that you also live forever, even after death. She takes the risk, and it doesn’t take long for the side effects to set in after she and Helen engage in a literally deadly fight to win the upper hand. Madeline and Helen – Mad and Hel – display the sick competitive female friendship that can take hold of two hurt people. Ernest is a bumbling buffoon, hardly a prize for either of them, but it’s not really about him anyway, it has never really been about any of the men before. Madeline and Helen are obsessed with each other, obsessed with their own flaws, and have been playing this game since their relationship began. Both of the women struggle with low self-esteem and crippling fear that manifests as spite. Bruce Willis, by the way, wasn’t the first choice to play Ernest, but he was very eager to join the film after Kevin Kline had to decline due to scheduling conflicts.

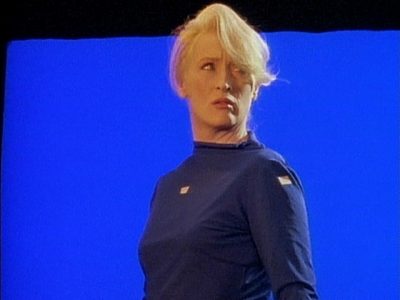

“It was meant to be Night of the Living Dead, if George Cukor had directed it,” writer David Koepp told Vanity Fair in 2017 for the films 25th anniversary. “It felt like no risk whatsoever, because we both had nothing but credit-card debt to our names. There was nowhere to go but up.” Koepp and co-writer Martin Donovan imagined their project as a modest indie movie, perfect for big names of yesteryear like Ann Margaret, Tuesday Weld, and Dean Stockwell. “In our wildest dreams,” said Koepp, “the budget was about $5 million.” But once Universal sold Zemeckis on Death Becomes Her, their would-be B-movie began to blossom into something bigger, bolder, and more bizarre. Despite its central theme of women frenemies, “Death Becomes Her” is a deeply technical masterwork, groundbreaking in its invention for years to come. By the early 1990s, Industrial Light and Magic had already been innovating in digital visual effects in a major way with films such as “The Abyss” and “Terminator 2: Judgment Day”. Then came along “Death Becomes Her”. It would go on to win the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, thanks to more innovation from ILM and practical creature effects by Amalgamated Dynamics, Inc. To produce the shot of Meryl Streep’s character appearing to have her head twisted backwards, three live-action background plates were filmed. The first was with Meryl wearing a stretchy blue hood over her head and walking backwards. The second plate was a clean plate, and the third involved Meryl performing in a blue bodysuit against a bluescreen. The blue hood was digitally removed from the first plate and replaced with the corresponding area from the clean plate using black- and-white mattes created using Parallax’s Matador Paint system. Meryl’s head from the third plate was extracted from the bluescreen and match-moved into position. Finally, a computer-generated twisted neck piece was modelled, animated and matchmoved to fit between Meryl’s body and extracted head using a combination of Softimage 3D animation software and custom ILM software. It was rendered in RenderMan and then composited together. Additional paint work was also required. Visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston also remembered the inventions to realise Meryl’s head stretching scene in an interview with vfxblog:

It took us a long time to get there. I actually had a hair piece done that looked like Meryl’s hair. As if, it had to be shot this way, first of all. The body is a dummy, the hands I don’t think are even Meryl’s hands. Meryl is behind her, right over the dummy. But we’re going to have to replace all of her neck and her shoulders and everything as she raises up and drops back down. So because everything was so hard to do, including hair, I had her wearing in front of her neck, like almost like a beard, a long piece of hair that looked like her wig hair. In case I needed it to patch things, once the CG neck started going in there. And I know that she didn’t know what the hell was going on. Bob [Zemeckis] had her come over to me and just said to Meryl Streep, he said “Whatever Ken asks you to do, no matter how silly, just go with it. You can trust him.” Cause she must have been thinking, “What am I, what is this stupid thing?” (Ken Ralston, vfxblog, July 30, 2017)

Many scenes were deleted from the final version – even a complete storyline and the original ending for the film were left on the cutting floor. According to Zemeckis, even or eight actors with speaking roles were cut from the film. While they have never been released, many of those scenes can be found in the film’s theatrical trailer and on international lobby cards (such as Jonathan Silverman’s part as Madeline’s agent, or Ernest putting Madeline into the freezer after her accident). Many scenes from the trailer were shot from different angles than the final scenes in the film, and a couple of more deleted scenes have been used in the film’s promotional featurette. The biggest omission from the film is Tracey Ullman’s supporting role. After escaping death at Lisle’s party, Ernest visits a bar and meets a bartender named Toni, played by Ullman, who listens to his wild story and offers him shelter. When another visitor at the bar suddenly dies from a heart attack, Ernest and Toni have a plan. She calls the police and tells them that the man is Ernest. As he has no visual ID the police need a next of kin and at that moment Madeline and Helen appear and they have to identify him. However, before they see his face, Toni gives them the potion which they take as prove and leave. Toni has hidden Ernest in her car, they declare their love and head off to Switzerland. Years later, Madeline and Helen meet them strolling along – old but happy. While some of the cast liked this ending, the test screening audience did not so Zemeckis added the ending that was darker. Cutting this scene also meant removing Toni’s scenes completely.

While its visual effects won praise, the film was savaged by critics. Between rough reviews and making just $58 million domestic on a $55 million budget, “Death Becomes Her” died with a whimper at the box office. In theaters, audiences were shocked and confounded by seeing such likeable female stars daring to play such devious dames. (Variety’s review clutched its pearls over Streep’s “commanding shrillness” and Hawn’s “abrasive demands.”) Meryl Streep has been vocal about her dismay of the technical aspects of filming, but it would be wrong to say she disliked the film. She told Entertainment Weekly in 2000: “My first, my last, my only. I think it’s tedious. Whatever concentration you can apply to that kind of comedy is just shredded. You stand there like a piece of machinery – they should get machinery to do it. I loved how it turned out. But it’s not fun to act to a lampstand. ‘Pretend this is Goldie, right here. Uh, no, I’m sorry, Bob, she went off the mark by five centimeters, and now her head won’t match her neck!’ It was like being at the dentist.” Her work was honored, nevertheless, with a Golden Globe nomination as Best Actress in a Musical or Comedy. After lacklustre box office results, fans discovered “Death Becomes Her” on their own terms at home after its video-release. As Vanity Fair pointed out in its 25th anniversary celebration, the film has become a touchstone of the queer community. Madeline and Helen’s looks have inspired cosplay and untold drag performances. The film is screened during Pride month, where bar rooms and theaters full of fans mouth along with every line. “Death Becomes Her” even inspired a runway challenge on the groundbreaking reality competition series “RuPaul’s Drag Race”. The film has remained an elixir of life for its fans – one that not only spurs them to laugh at absurd vanity and suffocating heteronormativity, but gives them license to challenge those things – a fantasy of defiance and power, beauty and eternal youth.