|

Master Class

Vogue ·

December 2002

· Written by Laura Winters

|

The first time I met Meryl Streep was four years ago at the Toronto International Film Festival, at a dinner in honor of Dancing at Lughnasa. Streep arrived in a heathery tweed jacket, looking like an Irish countrywoman fresh off the moors. She disappeared before dessert; we found out later she had gone to be treated by a night-owl dentist for a cracked tooth. When I remind her of that night recently, she laughs, making light of it. “That’s being a movie star,” she says. “You can get a dentist at midnight in Toronto.” Getting a dentist at midnight is just one of the perks of being Meryl Streep. Another is that the entire Hollywood A-list is happy to talk about you. Yet another is that, at an age when many actresses in Hollywood have started hanging up their gloves, you have starring roles in two of the most high-profile and compelling films of the Oscar season: The Hours, based on Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, and Adaptation, after Susan Orlean’s best-selling book The Orchid Thief. Though Streep has appeared in countless guises over the years, she prefers to keep her personal side under wraps. She does few interviews, shuns the Hollywood social scene, and dedicates herself when she is not working to her four children (three girls and a boy, ages 11 to 23) and her husband, sculptor Donald Gummer. Her friend Jack Nicholson likens her to the Mona Lisa. “There’s this tremendous part of Meryl that I don’t know that anybody has ever seen,” he says. “It’s that old Gioconda smile, the mystery of her.”

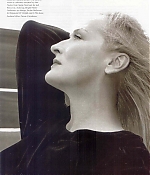

So I’m not surprised when it turns out that Streep doesn’t allow strangers into her home in Connecticut, or that arranging to meet her can become a full-scale diplomatic negotiation. But finally, late one August afternoon, she comes rolling up the driveway to the house where I’m staying in rural Connecticut, alone at the wheel of the car, her hair still wet from the shower. She’s dressed like a stylish soccer mom in a silky T-shirt, black pedal pushers, black sandals and a modish little pair of aqua-tinted sunglasses. She looks much younger than her 53 years; her oval face, with its high cheekbones, is almost devoid of makeup. In person, Streep is funny, approachable, and startlingly earthy. She talks about her household with pride and a bit of maternal aggravation. “We have a dog, two cats, and three fish, and they all-except the fish-get in the car and go back and forth with us between Connecticut and New York,” she says with a sigh. “The interesting thing about being a mother is that everyone wants pets but no one but me cleans the kitty litter.” That sly sense of humor is one of the first things that Streep’s colleagues all mention about her. “She has a wry, goofy wit,” says Kevin Kline, a friend since Sophie’s Choice. And Renée Zellweger, who played her daughter in One True Thing, remembers, “We used to make up Scrabble words between takes, not all of them appropriate for print.”

Carrie Fisher, one of Streep’s closest friends, puts it this way: “Meryl isn’t just this graceful person with luminescent skin. She’s also this other person-with this edgy humor and a way of double-thinking things.” What Fisher means by “double-thinking” is Streep’s tendency, at times, to agonize about her decisions. At the same time she can be surprisingly tough. Her friend Cher still recalls the time that Streep saved a woman in downtown Manhattan. “We were walking down the street one day,” Cher tells me. “We rounded a corner and saw this huge man attacking a woman in the street, trying to grab her purse. Meryl starts running toward him, screaming, and I’m thinking, Oh no, I’m going to get killed, but I start running toward him, too. And the man lets go of the woman and runs away.” If it’s hard to imagine the seductress of The French Lieutenant’s Woman running down the street after a mugger, that’s the essence of Streep. She is reserved and yet impassioned; classy and yet ribald; Mona Lisa and the woman next door. As Clint Eastwood, her costar and director in The Bridges of Madison County, says, “she can play vulnerability without playing the victim.” And her two upcoming films reveal two completely different sides of her: In The Hours she plays a thoughtful editor and mother, while in Adaptation she takes the role of a daring, flighty journalist. There is no reconciling the different sides of Streep: They only add to her overall mystery. One consistent thread in Streep’s career has been her resolute decision not to play the beauty card. “I think the most liberating thing I did early on was to free myself from any concern with my looks as they pertained to my work,” she says. “For an actress, worrying about appearance is a horrible, horrible trap. It’s great for acting to be unconscious of how you look and to be willing to mess up how you look, and see what that does to people.”

Of course, in those early movies like Kramer vs. Kramer and Manhattan, Streep was gorgeous, with her curtain of golden hair, finely etched features and cool aristocratic bearing. She could easily have played the blonde goddess; instead she chose to take on the myriad identities of a character actress while still managing to have the megawatt stature of a star. As a result, she has become a kind of beacon for younger talent. “Meryl opened the door for the audience to accept an actress playing a wide variety of roles,” says Gwyneth Paltrow, who hailed Streep as “the greatest one who ever was” during her Oscar-acceptance speech. And Claire Danes, who plays Streep’s daughter in The Hours, observes, “Seeing Sophie’s Choice when I was eight was the first time I really understood how provocative and profound acting could be.”

One of the serendipitous effects of Streep’s not playing the beauty card is that her career does not seem to have an expiration date. When I ask Streep about the difficulty of finding films with good roles now, she laughs wryly. “It’s a challenge,” she says. “I can’t stand most things that I see.” Which is why she embraced The Hours and Adaptation with such fervor. “These two projects just leaped out at me. It was like seeing two white unicorns making their way across that field.” The Hours traces a day in the life of three women whose lives are all affected by Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. Nicole Kidman plays Woolf herself in 1923, struggling to write her novel. Julianne Moore is a ’40s Los Angeles housewife reading the book. And Streep is Clarissa Vaughan, an editor in present-day New York planning a party for her friend and former lover Richard (Ed Harris), who calls her “Mrs. Dalloway” in a gibe at her prosperity and constant socializing. “For Clarissa we needed an actress, like Meryl, who could play contradictions, gray areas and genuine depth,” says director Stephen Daldry. In the film, Streep has some seismic scenes with Harris, in which Clarissa fights with the gravely ill Richard while secretly wondering whether she ruined her chance at happiness by leaving him long ago. “Meryl’s absolutely fearless,” Harris says. “There’s no place she doesn’t dare go in terms of her work.”

Streep speaks of Clarissa the way she would of an intimate, troubled friend. “She isn’t so different on the outside from what I look like-she’s a mother,” she says. “But I don’t think she’s like me. Of necessity I live very much in my life, and I think Clarissa lives, in great measure, in the past.” It seems fitting that Streep plays a woman who aspires to give a great party. What she herself has always done as an actress resembles what the most talented hostesses do. Spike Jonze was struck by this on the set of his film Adaptation during a dinner-party scene: “Meryl stayed at the table talking to everyone between camera setups and made it a real dinner party, with everyone relaxed and talking and laughing. She goes into a scene and helps set the mood, creates the right environment.” Adaptation is Jonze’s and writer Charlie Kaufman’s follow-up to their breakthrough comedy, Being John Malkovich. Streep plays Orlean, a New Yorker journalist who encounters John Laroche (Chris Cooper), a passionate orchid collector in Florida. The film also tells the story of a tormented writer named-what else?-Charlie Kaufman (Nicolas Cage), who is trying to adapt The Orchid Thief for the screen and who is suffering a massive case of writer’s block.

In its feverish mingling of Orlean’s and Kaufman’s stories, Adaptation is even wilder, and more ambitious, than Malkovich. “It’s not like anything I’ve ever played before,” Streep says. “But it’s about the best screenplay I’ve ever read.” She spent considerable time with Cooper on sets that re-created the Fakahatchee swamp in Florida, home of the elusive “ghost orchid.” “We spent whole evenings standing in muck, improvising our way into and out of scenes,” says Cooper. In Adaptation, the endlessly mutable orchid is a symbol of passion and mystery-an apt image for Streep herself, who changes so entirely for each of her roles. Nicholson still talks about watching her morph during the rehearsals of Ironweed. “There sits Meryl, with all her attention and her energy,” he says. “And then, little by little, after about the second day, this other person, Meryl’s character, has arrived at the reading.” Jeremy Irons had a similar experience with Streep, filming their big love scene in The French Lieutenant’s Woman. “When Meryl walked into the makeup room that morning, she walked in as my lover,” he recalls. “And all day, when we did the scene, she created this little box of reality around us. But that evening, when I went to dinner with her and Don and their kids, she had become Meryl, mother, again.”

From early childhood, Streep was obsessed with transformation. When she was little, she would draw age lines on her face, pretending to be her own grandmother. In her first successful metamorphosis, she became a homecoming queen in high school. She followed her calling, famously, to Vassar and to the Yale School of Drama, where she became known for her intense, workmanlike approach to her craft. “Meryl wore overalls a lot,” her contemporary at Yale, Wendy Wasserstein, recalls. Along with actresses like Sissy Spacek and Diane Keaton, Streep was shaped by the fervent consciousness-raising of the late ’60s/early ’70s. As Spacek says, “We were anti-glamour; we didn’t want to be just the girl on somebody’s arm. It was a time when we were all fighting for equal rights, and the social upheaval gave us great strength in our creative lives.” Coming out of this changing climate, Streep played, beginning in 1979, a string of ornery, controversial women. There was no accent she couldn’t do, no character too exotic for her to play. But as a result there was practically a public outcry when Streep tried to embark on a series of comic roles in the early ’90s. “How you first meet the public is how the industry sees you,” she says ruefully. “You can’t argue with them. That’s their perception. You just have to keep on doing what you do. It’s the lesson I get from my husband; he just says, ‘Keep going. Start by starting.’ ”

Streep’s husband comes up often, in spite of her efforts not to talk about him. “He hates to be written about in my movie stuff,” she says, smiling. When I ask her the secret to such a long-lived marriage, she doesn’t hesitate. “Goodwill and willingness to bend-and to shut up every once in a while.” She goes on, “There’s no road map on how to raise a family: it’s always an enormous negotiation. But I have a holistic need to work and to have huge ties of love in my life. I can’t imagine eschewing one for the other.” True to her ’60s upbringing, Streep also makes room for activism. Last December she moderated a press conference on behalf of Afghan women at the New York offices of Equality Now. “I’ve been reading for years about the Taliban treatment of women,” she tells me, “and it got my blood boiling. As the mother of three girls, and the daughter of an independent woman, I can’t imagine that.” Near the end of our visit together, I ask what it felt like to play the emotionally tortured Clarissa, and her answer is surprisingly frank. “It was a nightmare,” she says. “And yet, this is why you sign up. You want the challenging work, you search for it, you berate your agent because it doesn’t exist. And then when it comes, the night before you’re supposed to shoot the scene, you think, Why did I say I would do this?”

She pauses, then smiles. “But there’s nothing like the moment when you first read the script,” she says. “You start reading, and suddenly your heart starts to race. Suddenly you’re interested in the world again, and heartened or enlivened or angry. I don’t have to analyze this; I just know the feeling when I get it. And, believe me, I need it like food.”