A deeply personal story from America’s funniest director sheds light on a family’s struggle with a child’s epilepsy and the American healthcare system. In one of her rare appearances on television, Meryl Streep plays a tiger mother going to lenghts to find a miracle that can cure her sick child.

I don’t think any director has made us laugh more in the 1980s and 1990s than Jim Abrahams, best known as a member of Zucker, Abrahams and Zucker team that brought us “Airplane”, “Top Secret”, “Ruthless People” and “The Naked Gun” series. But Abrahams’ private life took a serious turn when his young son was diagnosed with epilepsy. Charlie would convulse and lose consciousness. Medications didn’t help. As his seizures continued, his cognitive abilities slowly deteriorated. Jim, who wasn’t a medical doctor, decided to start investigating alternative treatments. After days in the library looking through books and medical journals, he found a book on childhood epilepsy written by Dr. John Freeman, the director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Center at Johns Hopkins Hospital. The book described that a diet that mimics the metabolism of starvation by cutting most dietary sources of carbohydrates and proteins could in some cases cure drug-resistant childhood epilepsy. Ignoring the warnings of the staff at the boy’s hospital, Jim transferred his son to the epilepsy center in Maryland, and Charlie was started on the diet. The young boy immediately showed improvements in his condition, and a couple of years later he became seizure free. Even the mental setback turned out to be reversible.

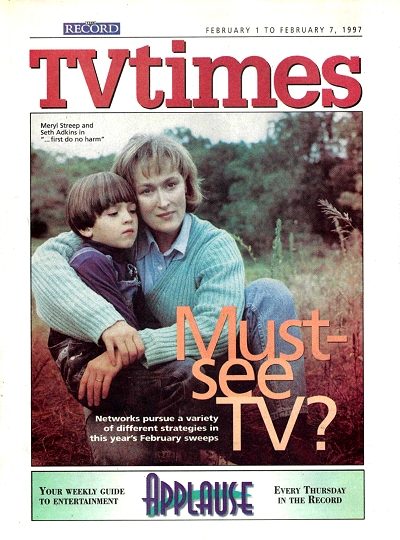

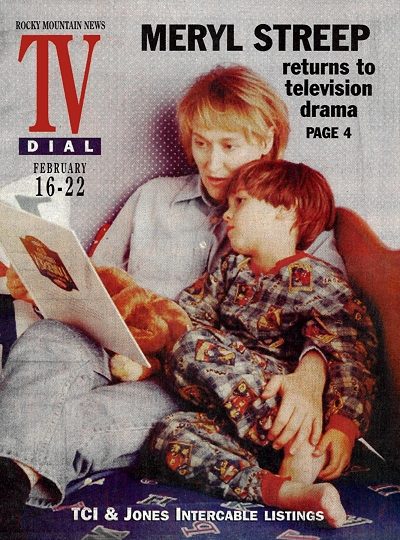

Although the film plot has parallels with the Abrahams’ story, the character of Robbie is a composite one and the family circumstances are fictional. Four-year-old Robbie (Seth Adkins) is diagnosed as having a type of epilepsy for which the cause is unknown. His parents, Lori (Meryl Streep) and Dave (Fred Ward), agree to a series of excruciating drug treatments which only seem to worsen his condition. Their situation becomes more complicated when they learn that their health insurance policy has lapsed. Then Lori discovers a regimen called the Ketogenic Diet; one-third of the epileptic children on this diet have experienced no additional seizures. Robbie’s parents are furious with his doctor (Allison Janney) for not telling them about this treatment and then refusing to facilitate their trying it. Instead, she recommends brain surgery for the boy. Several minor characters in the film are played by people who have been on the ketogenic diet and had their epilepsy “cured” as a result. The dietitian Millicent Kelly plays herself. Charlie Abrahams appears as a young boy playing with Robbie in the hospital, whose mother quickly removes him when she discovers Robbie has epilepsy—as though it were an infectious disease. Commenting on the film, John Freeman said “The movie was based on a true story and we see this story often, but not everyone is cured by the diet and not everyone goes home to ride in a parade.” He later noted that the film had “fueled a grass-roots effort for more research on the diet.”

The ketogenic diet was developed by Russel Wilder at the Mayo Clinic in 1921. The diet aims to reproduce some of the metabolic changes seen during fasting. Fasting had been shown to be effective in treating epilepsy but is obviously not sustainable. Although initially popular in all age groups, the diet was largely replaced by effective anticonvulsant medications beginning with phenytoin in 1938. It remained a treatment of last resort in children with intractable seizures. Since the film was produced, the diet has seen a dramatic revival with numerous published research studies and it is now in use at 75 epilepsy centers in 45 countries.

I was pregnant with my youngest about the same time that Nancy was pregnant with Charlie. And when he was about a year old, Charlie began to manifest symptoms of epilepsy. So I was familiar with their ordeal as they sort of negotiated this medical labyrinth to find a treatment for him that would make him better. He had a miraculous reaction [to the Ketogenic Diet]. From 90 seizures a day, he had none! This was a project that we’d talked about making as a feature. But we thought seven people would see it. And we thought the best way to get the largest possible audience would be to put it on TV. (Meryl Streep, Deseret News, February 13, 1997)

Abrahams and Streep became friends when their children both attended the same school. She was an early supporter of Abrahams’ Charlie Foundation and appeared in an 1994 informational video Abrahams produced to get the word out about the diet. That video, in turn, prompted an enormous amount of mail to both Streep and Abrahams. “And one of the letters was this story that we have dramatized here,” Streep said. What that audience is going to see is a stunning story that seems unbelievable – but it’s true. If it’s hard for viewers to understand how doctors could ignore the Ketogenic Diet, Abrahams thinks he’s come to understand it. Not that, once again, doctors will like his interpretation. “A neurologist looks at it from the point of view of someone who’s never held his child while he’s having a seizure, has never seen his child’s eyes roll back in his head, has never been sitting in a waiting room when they were carving up his child’s brain,” Abrahams said. “The problem with the Ketogenic Diet, I think, is that it doesn’t come in pill form. There is no drug company selling it to the neurologist. It can’t be administered by a scalpel. So there’s no hospital that’s really an advocate that will profit from it.”

“…First Do No Harm” was well received upon its television premiere in February 1997. The Los Angeles Times wrote in its review: “Should television drama, with its inherent capacity to persuade via the subtle use of character, story and music, be used to advocate specific agendas? It is a good question. Yet specific agendas are advocated constantly – sometimes intentionally, sometimes unconsciously or covertly. In the case of “…First Do No Harm,” which is a fictionalized dramatization inspired by actual events, what is ultimately more important is that this family drama champions an even broader point, one that reaches well beyond epilepsy and the controversial Ketogenic Diet: the importance of taking responsibility for one’s own health. It is a point well worth making, regardless of one’s opinion of specific medical procedures at issue here. The most moving and most liberating scenes in the picture are those in which Lori finally refuses to allow the accountability for her child’s health to be made solely by others. Streep’s touching veracity in those scenes takes this compelling story out of the realm of advocacy and into the arena of fascinating television drama.” Meryl Streep received Golden Globe and Primetime Emmy nominations for her performance, but didn’t win. Today, the film is a rare find, but if you ever get a chance to see it, don’t miss it.

The Record

February 01, 1997

|

Rocky Mountain News

February 16, 1997

|

Reading Eagle TV Times

February 16, 1997

|