|

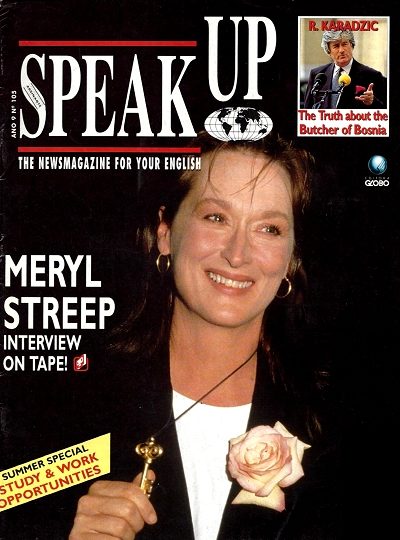

Simply Streep is your premiere online resource on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her acclaim to be one of the world's greatest living actresses. Created in 1999, Simply Streep has built an extensive collection over the past 25 years to discover Miss Streep's body of work through thousands of photographs, articles and video clips. Enjoy your stay and check back soon.

|

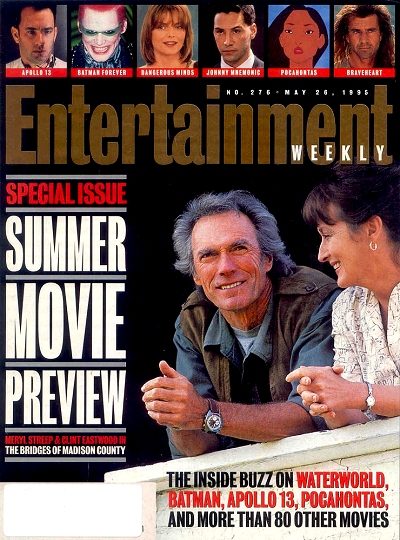

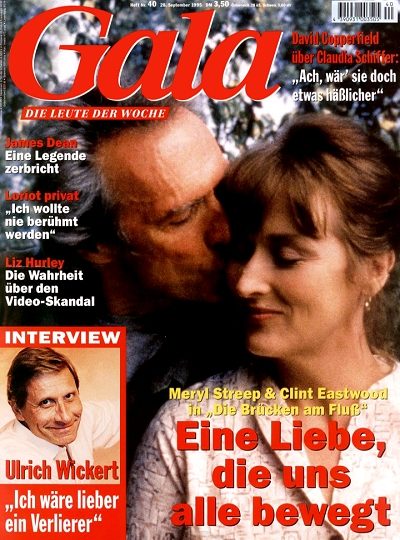

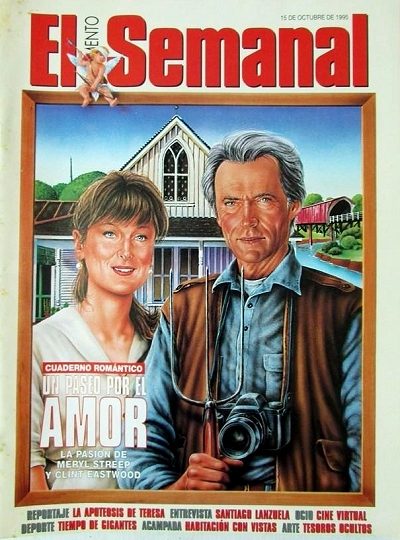

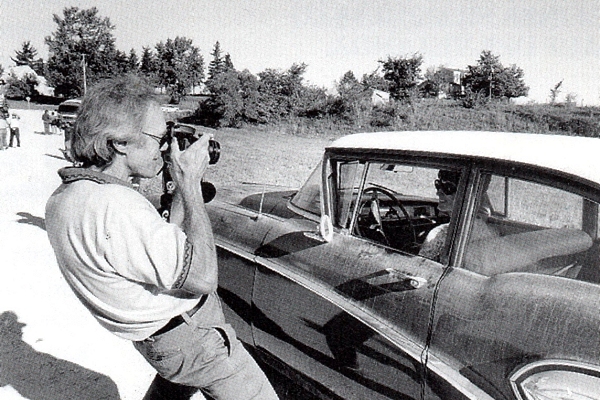

In the mid-90s, Meryl Streep’s career was revitalized by a most unlikely leading man and director. Clint Eastwood – Western hero, movie star, director and America’s man’s man – turned Robert James Weller’s kitschy best-selling novel into a tender box office hit for grown ups. Fresh off his multiple Academy Awards wins for “Unforgiven”, Eastwood took over directing duties from Steven Spielberg after being cast in the male lead – and stood by his casting choice that was unheard of in Hollywood – casting a 45-year-old woman to play a 45-year-old woman.

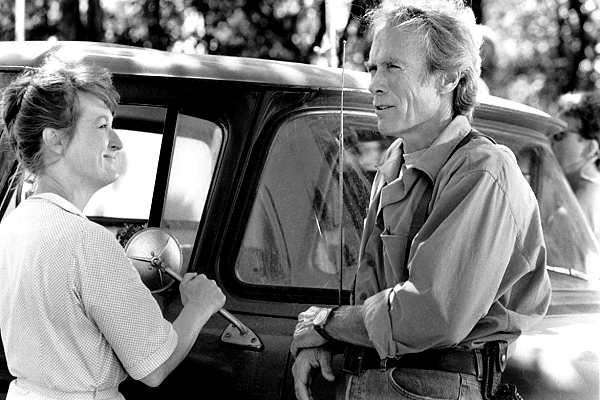

Robert James Waller’s novel (called “arguably the world’s longest greeting card” by the New York Times) about the four-day love affair between a travelling professional photographer who had come to Madison County, Iowa, and a Italian-American housewife whose family was way, was optioned by Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment before its publication in 1991 – by the time of the film’s release, the novel sold 9.5 million copies worldwide. Spielberg wanted to produce the film with Amblin and first asked Sydney Pollack to direct, who got Kurt Luedtke to draft the first version of the adaptation but then bowed out. After a second draft by Ronald Bass fell through, a third draft of the script by Richard LaGravenese was liked by Eastwood, who quite early had been cast for the male lead, and by Spielberg, who liked LaGravenese’s version enough to consider making Bridges his next film after “Schindler’s List”, which was in post-production at the time. Both men liked that LaGravenese’s script presented the story from Francesca’s point of view. Spielberg then had LaGravenese introduce the framing device of having Francesca’s adult children discover and read her diaries. Somewhere along the road, Spielberg decided not to direct it after all, and after his next best choice Bruce Beresford dropped out as well, Eastwood decided he could direct it as well. His last directorial effort, “Unforgiven”, won him two Academy Awards for Best Director and Best Picture, as well as a Best Actor nomination.

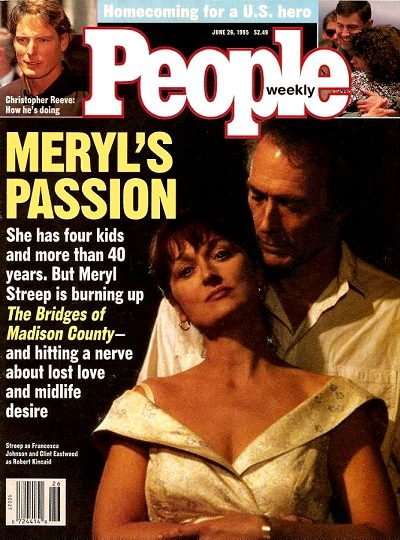

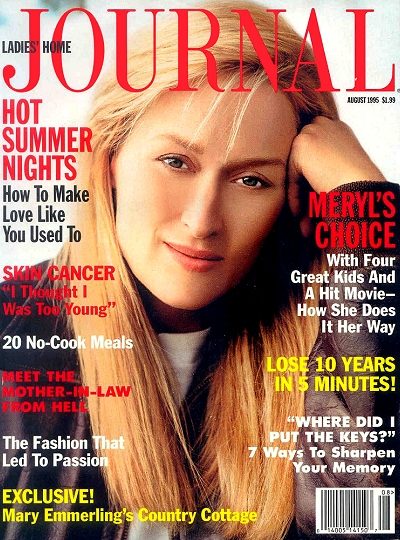

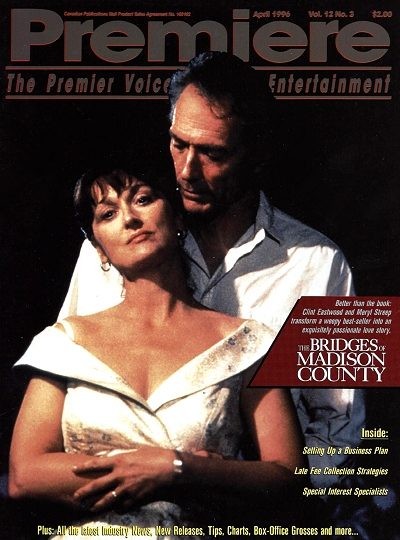

While Meryl Streep wasn’t the studios’ first choice for the lead role of the Italian-American warbride – Warner championed Isabella Rosselini for her part – Eastwood always had Streep on top of his list. But the actress had declined a first offer already because, as she told Entertainment Weekly back in the day, she didn’t like the book and didn’t even finish it. The studio considered pretty much every actress in her early ’40s for the part – Anjelica Huston, Jessica Lange, Mary McDonnell, Cher, and Susan Sarandon – but Eastwood, on his mother’s advice, was persistent and sent the final draft of the LaGravenese script to Streep. Her reluctance passed, as “the screenplay had a woman in it. I had a picture of who this was – I knew it was an Italian war bride, and I had grown up down the street from one. Her husband was a tall, blond man, and she barely spoke any English. Over the years she learned – she was a very bright, interesting woman – but there was always something exotic about her. Anyway, the book had this woman in jeans and braless. It was just hard for me to understand her. I had a pretty vivid picture of her, and I didn’t want to complicate it with the authors actual intent.” As Janet Maslin described the character in her review, “Francesca is a very different woman from any [Streep] has played before. There’s a carnality to this performance that makes sense of the character’s longings and gives flesh to Mr. Waller’s overheated daydreams. As Francesca straightens her dress or touches her mouth or smooths loose wisps of hair, Ms. Streep conveys a sexual tension that the film’s languid pace helps heighten. She does a remarkable job of suggesting this isolated woman’s long-lost hopes and dreams. Not to mention her astonishment at suddenly finding Clint Eastwood peeling carrots in her kitchen while her husband and children conveniently spend four days with a prize steer at the Iowa State Fair. When that passion arrives, both these actors do more kissing on screen than either has done in a whole career, yet the tone isn’t torrid. Instead of frankly sexual, it’s fond, cuddly and warmly affectionate, confirming the sense that this story’s romance-novel sensibility reflects a conventionally feminine point of view.”

In the book, Francesca is not an especially strong character – things happen around her and she’s swept up in the current. LaGravenese’s screenplay rectifies this, creating a dynamic personality for Streep to work with. In fact, the actress commented that she was “blind to the book’s power” but thought the script was “beautifully crafted.” There aren’t many intelligent motion picture romances. It’s easy to believe that Francesca and Robert’s love is deep and special, but perhaps the real test of the film’s power is whether the statements, situations, and characters transcend the screen to leave a lasting impression. Not many pictures are created with the necessary skill to challenge our perceptions and beliefs, but The Bridges of Madison County is a rare exception. Principal photography took place in September 1994 and last only 42 days. Eastwood filmed it chronologically from Francesca’s point of view, “because it was important to work that way. We were two people getting to know each other, in real time, as actors and as the characters.” It was filmed on location in Madison County, Iowa, including the town of Winterset, and in the Dallas County town of Adel. The Bell’s Mills Bridge, in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, was also a filming location. Meryl Streep rememebered the set as “the quietest she had ever worked on. Eastwood worked very fast”, she said, “never raising his voice above a whisper and rarely asking for more than one or two takes”. He also found time to write the main musical “love theme” for the movie called “Doe Eyes”, which was orchestrated for the film’s score by Lennie Niehaus. Eastwood also gave his son Kyle some onscreen time in the scene where Robert and Francesca visit a jazz club. Kyle, a real-life jazz musician with his own quartet, can be seen playing bass on stage with the James River Band.

“The Bridges of Madison County” released theaters in the Summer of 1995 to positive reviews and a number 2 spot at the box office (behind “Casper”). The New York Times wrote in their review, “to say that Mr. Eastwood has done the best imaginable job of directing “The Bridges of Madison County” is not to say that he has done the impossible. No one really could have made this book’s romantic fantasies feasible in the flesh. Still, Mr. Eastwood instills this story with the same soulful, reflective tone that has elevated his last few films, and with the wistful notion that life’s great opportunities deserve to be taken”. The Washington Post, critical of Streep’s “acting tics”, noted, “[her] method-school compulsions are warmed up by her robust, healthy demeanor. For an actor who normally registers a notch above dry ice, she actually exudes earthy sexiness, like some ’90s Anna Magnani.” And James Berardinelli wrote: ” Meryl Streep, who really shines. After taking a break from drama with the popcorn-munching adventure thriller The River Wild, she returns to the kind of role that made her famous, and gives perhaps her best performance since Sophie’s Choice.” For the first time since 1991, Meryl Streep was nominated at the Acadmey Awards again (five years being the longest time period in her career without an Oscar nomination, go figure) – alongside nominations for the Golden Globe and Screen Actors Guild Award. “The Bridges of Madison County” is Meryl’s best remembered film from the 1990s (in line with “Death Becomes Her”) and has stood the test of time, it is enjoyable today as it has been 25 years ago.