|

Simply Streep is your premiere source on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her the praise to be one of the world's greatest working actresses. Created in 1999, we have built an extensive collection to discover Miss Streep's body of work through articles, photos and videos. Enjoy your stay.

|

Celebrating

25 years

of SimplyStreep

|

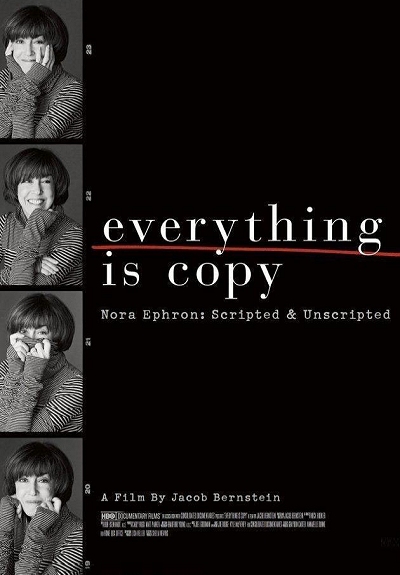

Everything is Copy

March 21, 2016

· HBO Documentaries

· 89 minutes

|

Directed by Ephron’s son Jacob Bernstein and Nick Hooker for HBO, Everything is Copy documents Ephron’s triumphant journey from tenacious New York Post reporter and acerbic magazine columnist to prolific literary sensation and comedic screenwriter supreme to in-demand director and all-around cultural icon. Packed with archival footage and incisive interviews with Ephron’s wide array of friends, family, artistic collaborators, and industry peers, Everything is Copy is documentary portraiture at its most lovingly detailed, warmly inclusive, and expectedly hilariously. You’ll laugh louder at Liz Smith succinctly swatting away any and all fond memories of Ephron’s eccentric first husband Dan Greenburg than you will at almost any studio comedy released this year. The acclaimed, gravel-voiced journalist Marie Brenner delectably holds court throughout the documentary while dishing on the philandering ways of Ephron’s notorious ex-husband Carl Bernstein, the Watergate hero who became persona non grata in New York social circles after Ephron turned the end of their marriage into Heartburn, a barely-veiled roman à clef that eventually became a studio comedy. In moments like these, Everything is Copy is rip-roaringly funny, like being the busboy at one of the Upper East Side’s most enviably gabby, three-hour lunches. But like the bulk of Ephron’s filmic output, these comedic elements are complemented by insights and interactions that are heart-stirring and throat-catching in their bittersweetness. (The Lincoln Center staff should really be handing out buckets or, at the very least, Kleenex before each screening.) I expect few onscreen moments to be more moving this year than Ephron’s frequent leading lady Meryl Streep openly reckoning with the self-imposed secrecy surrounding Ephron’s death in 2012, Nora’s sister and fellow writer Delia Ephron mistakenly uttering “When we died…” while discussing her loss, or the mere sight of the late Mike Nichols, his November passing still bitterly fresh in our minds, talking about his dear friend and constant creative partner.

It has been three years since Ephron died of pneumonic complications from the blood disorder myelodysplasia, a disease she had been fighting for six years but never disclosed to the public and which even some of her closest friends were kept in the dark about. Ephron never talked or (directly) wrote about her diagnosis, which is understandably surprising for a writer who turned any number of personal crises into flavorful works of fiction and who famously lived by the film’s titular phrase, a pithy advisement imparted by her mother, who was herself a writer and Hollywood hired hand, that means, quite simply, all of life’s experiences make for good material. It is this seeming contradiction — How could one of our most proudly personal writers avoid writing about the most personal development of all? — that becomes the core mystery at the center of Everything is Copy. It isn’t exactly answers that Bernstein, his fellow filmmakers, and the project’s participants are seeking. Only Ephron herself could say why she curtained off the darkest moment in her life with almost iron-clad resolution, only subtly alluding to it in some of her later works, like her 2006 essay collection I Feel Bad About My Neck, filled with thoughts on aging, existence, and the “d” word; or her final film Julie and Julia, in which Julia Child’s plucky yet plaintive life bears poignant reflections about marriage and sisterhood; or Lucky Guy, her Broadway play about salt-of-the-earth Post reporter Mike McAlary, a man to whom Ephron felt an unexpected kinship, according to star Tom Hanks and director George C. Wolfe. These projects are plumbed for deeper meaning and the efforts reveal plenty, but like all biographic documentaries of this nature, the filmmakers can only obtain so much from a subject who maybe wasn’t always as yielding as we like to remember.

Thankfully, more often than not, Everything is Copy simply lets Nora Ephron speak for herself by way of old interviews, television appearances, and audiobook narrations, and it’s through this obvious but necessary decision that the film excels at honoring the frank, funny, and tough-minded voice that was unmistakably Ephron’s and gloriously Ephron’s alone. In a scattered series of segments, some of Ephron’s best writing is read aloud by an appealing group of female interpreters who were Ephron’s friends and colleagues, including Lena Dunham, Gaby Hoffmann, Rita Wilson, Reese Witherspoon, and Meg Ryan, who is also dearly missed, although for much more frustrating and frankly fixable reasons. But it’s even more of a delight to see Ephron handle her own sparkling prose, reciting particularly juicy passages from Heartburn about her exes or detailing her primary sexual fantasy that should be recognizable to anyone who has seen Ephron’s most golden comic masterpiece When Harry Met Sally…, all while maintaining that remarkably straight face that tends to wrinkle into a frisky, satisfied smirk upon landing the punchline. Bernstein admirably doesn’t ignore his mother’s detractors and pays brief but due attention to the (frequently male) critics who opposed her highly-personalized art and relished the chance to pick at her occasional misfires. (Mixed Nuts and Hanging Up get their screen time, while the Razzie-winning Bewitched is luckily nowhere to be found.) But Bernstein and Hooker also recognize Ephron’s fiercely and regularly vicious streak of comedy, a side of Ephron that was plainly, as Barbara Walters puts it, “mean.” (I like to think that, somewhere, Ephron is still cackling at her own unrelenting pegging of First Daughter Julie Nixon as “a chocolate-covered spider” on The Dick Cavett Show, a clip that features deliciously in the film.)

Everything is Copy rightfully realizes that these traits were all a part of the woman Ephron was, unapologetically so. The film captures the intellectual and insouciant Ephron we’ll always have, but it appealingly gets at a more rounded vision of her too, a deeply protective Ephron who wrote not only to cover the internal bruises, but also because she loved it. One doesn’t replace or justify the other, and it’s this astute level of knowledge that really makes Everything is Copy such a special, heartfelt, and finally enlightening endeavor, not merely for Ephron’s devotees, but for all viewers (and not solely the female ones, as some will probably imply) who want to be moved, humored, and inspired by a woman who — to paraphrase Ephron herself — could only become her own heroine because she simply had no time for victimhood, which certainly goes a long way in shedding light on the strangeness of her quiet and self-preservative passing. Ephron’s bountiful but abbreviated life is a master class in how to take pride in one’s talents and pursue them with all the certitude and focus that so many of us lack as we only run around in circles, either too timid or distracted to really write ourselves as the true protagonists of our own lives. In a way, we’ve never needed Nora Ephron more, but as Everything is Copy is sure to remind you, we’ll never stop needing her either.