|

Simply Streep is your premiere online resource on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her acclaim to be one of the world's greatest living actresses. Created in 1999, Simply Streep has built an extensive collection over the past 25 years to discover Miss Streep's body of work through thousands of photographs, articles and video clips. Enjoy your stay and check back soon.

|

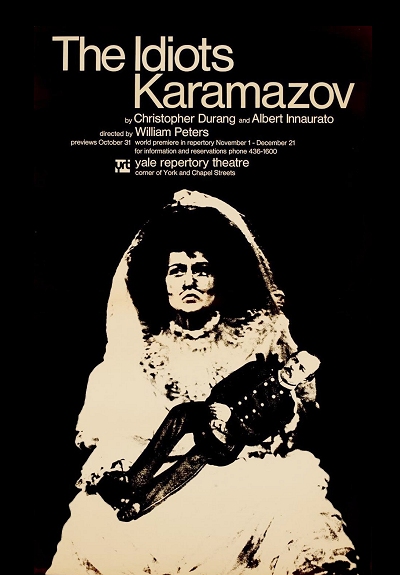

The Idiots Karamazov

November 01, 1974

· Yale Repertory Theatre

|

Playwright and actor Christopher Durang recalled the origins of “The Idiots Karamazov” in a profile for the Yale School of Drama’s 75th year in The New York Times in 2000: “In college I had made a very strange but tongue-in-cheek silent movie about “The Brothers Karamazov”. I played Alyosha, the monk, in it. At Yale, I showed it to Albert (Innaurato). I wanted to write a musical based on the novel. We came up with our own version – “The Idiots Karamazov – in which the novel gets mixed up in a crazy way with Chekhov and O’Neill. Meryl played the part – and she was wonderful – of the Russian translator Constance Garnett. Then Robert Brustein decided to do “The Idiots Karamazov” at the Yale Rep and cast me as the monk Alyosha. So I ended up getting my Equity card almost as soon as I graduated.

The star role is the translator, Constance Garnett. As portrayed by Meryl Streep, she is a daft, old witch (the play is daft, too) in a wheelchair, attended by a butler named Ernest, who eventually blows his brains out. Miss Garnett leads us through the Karamazov saga, offering absurd footnotes and marginalia (such as the conjugation of the verb Karamazov).

The focal character of all this nonsense is Constance Garrett. Looking like a somewhat more affable Wicked Witch of the West, she narrates and stage manages the play from her wheelchair. Meryl Streep’ performance in the role is superb, and although her diction is not always clear, she delivers the critic’s view with a true sense of drama: “Why must writers be so concerned with matters sexual?… Do I need sex? No”. Ernest Hemingway (“Oh, he’s so moody”) is her servant, pushing her around the stage as she yells page numbers and opens the representative vignettes. Appreciation of the satire does not occur without a prior knowledge of the “Too Great” books.