|

Simply Streep is your premiere source on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her the praise to be one of the world's greatest working actresses. Created in 1999, we have built an extensive collection to discover Miss Streep's body of work through articles, photos and videos. Enjoy your stay.

|

|

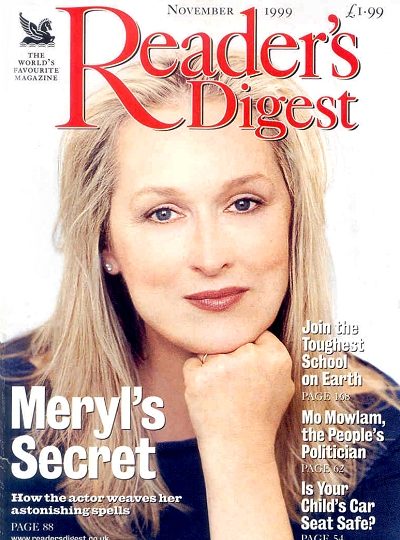

The Spark She Can't Explain

Reader's Digest ·

November 1999

· Written by Lawrence Elliot

|

Meryl Streep does not look fetching. Curled into a fetal position on a dishevelled bed, clutching a flannel bathrobe, her empty eyes contemplate the future of a woman whose husband has just left her.

This is the opening scene of Streep’s new picture, Music of the Heart, the trye story of Roberta Guaspari, a music teacher who taught a generation of ghetto kids to play the violin. But before that, Roberta was down and out, and this has to be established quickly. “Roberta, you’ve got to get out of that bed,” her mother says off camera. “Come down and have some breakfast.”

There is a barely perceptible cringing of Streep’s shoulders; she seems to be compressing herself, striving to vanish from this time and place. Streep has not yet spoken a word, but we already know the depth of this women’s wound.

How does she do it? How, in an industry abounding in gifted performances, does Meryl Streep stand in “a category unto herself,” as Dustin Hoffman, her costar in Kramer vs. Kramer, put it in an interview with Ladies’ Home Journal.

It’s a question many have asked, and Streep herself is no help. She has no method, she will tell you. “I don’t know how it works,” she said once. “I don’t know how other people do it. I’ve seen Robert DeNiro writing lots of things in the margins of his script, but I don’t know what he’s writing.”

Joseph Papp, the New York theatre producer who gave Streep her first professional role, suggested part of the answer. “There are only a few people around I would call pure actors,” he said in an interview with Newsweek. “Meryl is one. She takes tremendous risks, both physical and emotional. I thought she was gonig to break every bone in her body when she threw herself on the floor playing Kate in The Taming of the Shrew. And there are certain actors who would never play a negative role because they fear that the audience would not like them. But Meryl doesn’t care, and she violates her classic beauty constantly.”

Streep’s first significant stage appearance dates back to a junior-high-school Christmas program in Summit, N.J. She sand “O Holy Hight” in impeccable French – although she had been studying the language only a short time. It’s a gift she could never explain, but a generation of movie-goers with sagging jaws have since listened to pitch-perfect replication of foreign accents to match the ancestry of the characters she has played – Polish, British, Danish, Australian, Italian and Irish.

But mimicry was not her only chameleonlike talent. At 15 she bossed her brothers around, had braces on her teeth and kinky mouse-coloured hair. So Streep transformed herself. The braces came off, the mousy hair was peroxed blond and soon she was a cheerleader and homecoming queen.

In her second year at Vassar, Streep got the lead in Strindberg’s Miss Julie – the first serious play she had ever acted in. “How do you know how to do that?” her friends asked, impressed. “I didn’t know,” she now says. “And I still don’t. It was jsut there.”

“It” survived three years at the Yale School of Drama, from which she graduated with a Master of Fine Arts degree and an incipient ulcer. That whole time she kept going from the joy of dreating a character to a lingering doubt that the theatre could be a life for the serious person she wanted to be. How could an actor contribute somethnig of significance to the world? And so in the spring of 1975, while her classmates scurried from audition to audition, she thought about becoming an attorney, and applied to take the law boards. But she had to perform the night before, overslept and took this as a sign that she didn’t belong in law school.

In a span of 16 months she had played eight theatre roles to glowing notices. Increasingly, though, her attention was turned to Hollywood.

Robert Brustein was dean at the Yale School of Drama when Streep was a student. He, too, has a theory about the source of her acting gift. “The secret of how she does it is in herself, in her great compassion,” he reflected recently. “Her entire career, every one of her performances, is animated by this inner spark, this humanity. That’s how she is able to identify with her characters; that’s how she feels thie feeelings and becomes so astonishingly believable in their skins.”

That believability – and humanity – was powefully mainfest in the 1978 film The Deer Hunter. In it, Streep played a steel-town woman waiting for her man to come home from Vietnam. She had perviously fallen in love with John Cazale, a fine young actor who was also in the cast. It was only her second film, and she would go on to win an Academy Award nomination for best supporting actress. It was as though both her career and her life were charmed. But in fact she was in the grip of mortal pain all through the shottong of The Deer Hunter – Cazale was dying of bone cancer.

After fulfilling her commitment to star in the TV series “Holocaust”, Streep spent the next months nursing Cazale. As reported in a biography of Meryl Streep by Diana Maychick, she moved into the hospital during his last weeks, reading to him in character voices, distracting him with her incredible mimicry, making him laugh. When he finally died in March, Streep was emotionally devestated.

She tried losing herself in work and rented the SoHo loft of her brother Harry’s good friend, sculptor, Don Gummer. Don’s fraternal support sparked something unexpected: The two were falling in love. In September 1978, she won an emmy for her roel in “Holocaust”. She and Don were married that same month.

Today, Meryl and Don are parents of a son and three daughters, ranging in age from 19 to eight. They come before anything else in her life. With typical understatement, Streep refers to herself as “an actress who goes home to her family when I’m finished working.”

Asked about fulfillment that comes from her profession, Streep says that it comes from seeing actors onstage bringing characters to full life who would otherwise have lain inert on the printed page.

That vivid sense of reality is striking characteristic of the women Streep has created in 27 films. They are often sexy, but sexuality is driven by a complicated and often contradictory inteligence. They can be difficult, vulnerable – lonely and sidesplitting funny.

Even when they are essentially unsympathetic, like Joanna Kramer, who leaves her husband and little boy in Kramer vs. Kramer, she imbues them with believability and a point of view. She wrote her lines for the critical courtroom scene in Kramer vs. Kramer, giving audiences a better understanding of the mother’s motivation.

Streep has stuck a distinctive path in other ways too. She does not live in Hollywood, but makes her home in rural Connecticut. She decides which scripts to consider partly on the basis of how long she will have to be away from her family. And she also weighs whether the movie enhances or degrades the world in which she and her children will live.

Given the media’s lust for movie gossip, she has been linked romantically with a number of leading men. All ridiculous, Streep says. But her fellow actors do seem to fall under the spell of her acting talent. “Whoever is playing the lover falls in love with her,” notes director Mike Nichols. “And whoever is playing the villian is frightened of her.”

Meryl Streep herself understands the power of great acting, for she has felt it from the earliest days of her career. “I would leave the theatre with my senses sharpened,” she remembers, “like being outside after a rain. Everything was more alive.”

It’s a feeling she’s given to million of moviegoers.

Posted on March 16th, 2025

|

Posted on February 24th, 2025

|

Posted on February 17th, 2025

|

Posted on February 15th, 2025

|

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|