|

Simply Streep is your premiere source on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her the praise to be one of the world's greatest working actresses. Created in 1999, we have built an extensive collection to discover Miss Streep's body of work through articles, photos and videos. Enjoy your stay.

|

|

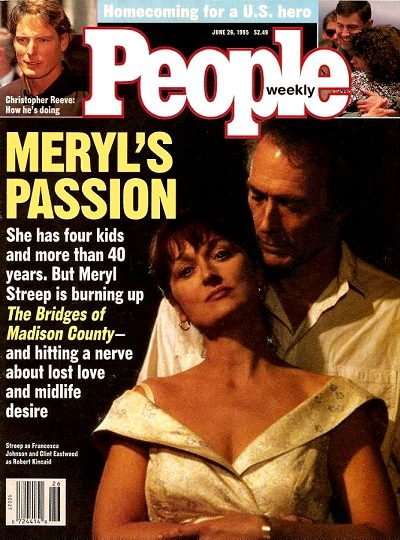

Heart Land

People Magazine ·

June 26, 1995

· Written by Shelley Levitt

|

As Clint Eastwood’s Onscreen Soulmate, Meryl Streep Gives America a Grown-Up Lesson in Midlife Longings and Last-Chance Romance In the final days of the five-week shoot of The Bridges of Madison County last fall, Meryl Streep did one of the many things she does better onscreen than anyone else: she cried. Filming an emotional scene in which her character struggles to say goodbye to her lover, the actress would show up on the set in Winterset, Iowa, at 9 in the morning and start to cry on cue. “Except for 45 minutes at lunch, Says her makeup man J. Roy Helland, “the tears were flowing for two days.” By the third day, her director and costar Clint Eastwood asked her to reshoot a couple of earlier, and happier, scenes, and Streep had to beg for a reprieve. “No amount of ice could possibly get Meryl’s eyes down,” says Helland. “They were so filled with fluid. There’s no glycerin with Meryl. When she cries, she cries.” Hers were not lonely teardrops. Some days the set was awash in tears-shed by fellow actors, visitors, even Teamsters on the crew. “Tears would start running down my cheeks,” says Jack Green, cinematographer for Bridges. “I’d try to brush them away when no one was looking, then I’d turn around and see Clint doing the same. Everyone was trying to look like they weren’t crying when they were.”

It has been much the same for moviegoers. Bridges shares with Casablanca the theme of a great passion discovered at midlife, only to be renounced out of a sense of duty. And seldom since that classic of 53 years ago has a screen romance touched so many so deeply. At the Sony Theatres Lincoln Square in Manhattan, a box of tissues sits atop the popcorn stand for moviegoers as they straggle out of Bridges. And it’s not only women who’ve been wiping their eyes. “I was giving out paper towels to the men,” says usher Eugene Streater at the General Cinema in Burlington, Mass. “They try to pretend they aren’t weeping, but they are.” Those floodgates have been open since 1992, when Robert James Waller’s novel was published. The four-hanky read has been an epic success, spending 149 weeks on The New York Times bestseller list (it’s currently at No. 2) and selling almost 9 million copies worldwide. Clearly, the simple story of a four-day romance between Francesca Johnson, an Italian war bride turned Iowa farm wife, and Robert Kincaid, a National Geographic photographer, has hit some deep cultural nerve. For some, the tale evokes poignant memories of the love that got away, for others it summons hopes of a soulmate yet to come. “I stayed married to a man for 28 years that I didn’t particularly love for the same reasons Francesca did,” says Anne Tompkins, 55, a teacher and divorced mother of two, as she leaves a Bridges showing in suburban St. Louis. “But I’m still hoping to find that perfect love. I’ll keep hoping until the day I die.” Bridges, which earned $24.9 million in its first two weeks, has become a hit in an unconventional way: by sidestepping the teenagers who make up a bulk of today’s moviegoing market. The audience for Bridges, according to Warner Bros., the studio that made the film, is made up overwhelmingly of people over 30. Gail Sheehy, author of the 1976 bestseller Passages, a study of life’s stages, surveyed 8,000 men and women 50 and over for her latest book, New Passages: Mapping Your Life Across Time. She believes that Bridges is a success because it depicts an overlooked reality: that passion springs eternal. “What came out emphatically in my research,” Sheehy says, “is that men and women over 50 are very much sexually alive, and those who aren’t really miss it.” In bringing the novel to the screen, Eastwood, in his capacity as director, and screenwriter Richard LaGravenese shifted the tale’s focus from Kincaid to Francesca. “What I was most drawn to,” says LaGravenese, “was the story of a woman in her mid-40s who had made certain choices and now thinks she will never experience passion again.”

Streep is the luminous center of the movie, earning critical raves and stirring talk of an Oscar. What seems astounding now is that she almost didn’t get the part. Eastwood faced strong opposition from certain powers at Warner Bros. when he proposed Streep as his leading lady. At 46, she is just a year older than the character she plays-Eastwood, at 65, is 13 years older than Kincaid-but the studio at first insisted on casting a much younger actress. “They were testing all these 30-year-old women,” Eastwood told The New York Times. “And it just shocked me…. There’s something about a woman who knows something that is more interesting.” Ultimately, Eastwood prevailed-and hired the woman he has described as “the greatest actress in the world.” She is certainly among the most acclaimed. Streep has earned nine Academy Award nominations-more than any actress save Katharine Hepburn and Bette Davis-and two Oscars, her first for Kramer vs. Kramer in 1980 and her second, three years later, for her portrayal of a Polish concentration camp survivor in Sophie’s Choice. Up to any challenge, she was a femme fatale in 1981’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman, a nuclear-plant worker in 1983’s Silkwood, a Danish noblewoman in 1985’s Out of Africa, a derelict in 1987’s Ironweed and an Australian mother suspected of murder in 1988’s A Cry in the Dark. Not just a highbrow actress, she proved herself a deft comedian in such films as 1990’s Postcards from the Edge and 1992’s Death Becomes Her. Francesca is the role that seems to come closest to Streep’s own soul. After 16 years of marriage and four children with husband Don Gummer, a 48-year-old sculptor, Streep was familiar with the feeling of middle-age restlessness roiling just beneath the surface of Francesca’s life. Explaining why she had taken on the unlikely role of an action hero in 1994’s The River Wild, she told Britain’s Daily Telegraph, “I wanted to get away from the caution in my physical life that I have gotten since I became a mother. I don’t do anything irresponsible or dangerous anymore.” But she took risks in Bridges as well. Abandoning vanity, she dyed her hair a dullish brown, close to her natural color, left her crow’s feet unconcealed by makeup, donned what she has described as “my tragic little housedress,” and showed off the extra pounds she’d gained. “I don’t think anybody has shot a love story weighing as much as I did,” she joked. Still, says cinematographer Green, shooting her was a joy. “She has beautiful skin, a perfectly shaped face,” he says. “The light fell on it perfectly.” Ironically it was Streep’s insecurity about her looks that originally inspired her gift for self-reinvention. The bossy older sister of two brothers, Streep was born in affluent Summit, N.J. Her father was a pharmaceutical executive, her mother a commercial artist. “I was ugly,” Streep has said. “With my glasses and permanented hair, I looked like a mini-adult.” Then, at 15, a transformation occurred. She had her braces removed, stopped wearing glasses, bleached her hair blonde and became a cheerleader and a homecoming queen at Bernardsville High School.

Attention agreed with her. At Vassar College, where she enrolled in 1967, she promptly became the star of the drama department, and afterward spent three exceptional years as a graduate student at the Yale School of Drama. She played no fewer than 40 roles at Yale and developed a reputation as a brilliant young actress. She also found herself with the beginnings of an ulcer. “It was terribly intense,” said Streep. “And I took it all in my stomach.” Gastric problems aside, Streep’s early career was charmed. After graduating from Yale in 1975, she moved to Manhattan and made her Broadway debut in Trelawny of the “Wells” that October. In 1977 she made her first movie appearance with a small part in Julia, followed by her role as Christopher Walken’s loyal girlfriend in The Deer Hunter, which brought her first Oscar nomination. For Streep, though, The Deer Hunter will always be connected with personal tragedy. At the time, she was living with actor John Cazale-best known as Michael Corleone’s weak brother Fredo in The Godfather and its sequel-whom she had met while appearing in Measure for Measure at the New York Shakespeare Festival in 1976. “He was large-hearted, very eccentric, and I loved him,” she has said. Before they began shooting The Deer Hunter, Cazale was diagnosed with bone cancer, and his condition deteriorated as the movie progressed. “Meryl stayed by his side every single moment,” director Michael Cimino recalls. “By her devotion to John, I knew she had great courage.” After Cazale’s death in March 1978, Streep moved from their apartment and sublet the Soho loft of Don Gummer, a good friend of her brother Harry’s, while Gummer took off for an extended vacation in Pakistan. A motorcycle accident cut his trip short, and when he returned home to recuperate, he and Streep fell in love, marrying in September 1978.

Their life together is, by Hollywood standards, extraordinarily private. Except for a three-year stint in the early ’90s that they spent in L.A., they have lived since 1985 in the hills of northwest Connecticut, on a secluded 89-acre estate with a 47-acre private lake. Respected by critics, Gummer may not have achieved the same level of success as his wife, but Streep credits him with giving her the support she needs to balance the stresses of her career and the demands of raising their four children-Henry, 15, Mary Willa, 11, Grace, 9, and Louisa, 4. “I couldn’t even dream of being a mother and making movies without Don,” she has said. “He’s the linchpin.” Streep’s own style as a mother is, literally, down and dirty. Kathryn Ireland Weiss, who, along with actress Amanda Pays, runs Ireland-Pays, a home-furnishings shop in Santa Monica, recalls running into Streep one day a year or so ago when they were both picking up their children from a play group. “The kids were all on the ground pretending to eat ham sandwiches made out of leaves and dirt,” she says. “Meryl squatted right down and pretended to eat one herself, and I have to say she was pretty darn good at it. After all, she’s Meryl Streep.” By the late ’80s, though, being Streep was no longer what it had been. Approaching 40, she found the flow of scripts slackening. Her attempts to recharge her career with comic roles led mainly to a string of movies that, at best, were marginally successful: She-Devil, Postcards from the Edge, Defending Your Life and Death Becomes Her. Starring in The River Wild, the story of a mother who takes her family on a whitewater rafting trip and winds up saving them from sociopathic robbers, was both a surprise choice and a coup. Streep said one reason she took the role, which added renewed momentum to her career, was to show her three daughters that action heroes didn’t need to be named Arnie, Sly or Bruce. If she made The River Wild for her daughters’ generation, she made Bridges for her own. Hollywood’s perception of middle-aged women as over the hill was strongly at odds with her own experience. “When I was in high school,” she told Entertainment Weekly, “and I was in a car with a boy and he was driving real, real fast, there was never an ounce of enjoyment of the thrill…. I’ve always felt about 40 [and] I did have this moment when I turned 40 that I felt like my clothes finally fit and I didn’t have to be anything other than myself.” Still, Streep, who has said, “I was blind to the book’s power,” wasn’t eager to play Francesca. But Eastwood phoned her at home to persuade her. His first challenge was getting past her babysitter, who thought he was Meryl’s father, Harry, doing an Eastwood imitation. His second was getting Streep to at least take a look at the script. She read it, she wept, she took the part.

By the time Streep arrived on the set in September, Francesca’s world had been faithfully recreated. An abandoned farmhouse had been cleared of raccoons and bats and fitted with Francesca’s chrome dinette set, antique dresser and porch swing. Streep felt at home immediately. “She saw her house,” says art director Bill Arnold, “and she took over. There was never any star thing, ‘I want this and I want that.’ Never.” In fact for a movie that involved two huge stars, this was an extraordinarily calm set. Eastwood’s style as a director was so quietly understated that makeup artist Helland made sure to wear his hearing aid every day. “Clint never yells ‘Action!’ ” he recalls. “He says, ‘Well, when you’re ready, start.’ ” Still, everyone knew there was something powerful going on. Eastwood had chosen to shoot the movie chronologically so that there would be a natural development of intimacy between Francesca and Kincaid. It worked. Many scenes were shot in a single take, and the movie finished well ahead of schedule and, at $22 million, far below the average cost of a Hollywood film. “The combination of the two of them made magic happen,” says Charles Breen, Bridges’ assistant art director. The chemistry didn’t end when the cameras stopped rolling. Between takes, says Christopher Kroon, 17, who plays Francesca’s son, “they’d dance together, hold and kiss each other’s hands, have fun.” That sort of thing, not surprisingly, led to rumors that the two had had a fling. To which both have replied, emphatically, Oh, baloney. Many on the crew say the same. The talk probably got a boost from the fact that Eastwood’s relationship with actress Frances Fisher, the mother of his 22-month-old daughter, who bears, coincidentally, the name Francesca, had apparently collapsed. But Eastwood wasn’t feeling any Kincaid-like yearnings to quote Yeats or pick wildflowers. Describing his ideal evening to The New York Times, he said, “I have two Budweisers in front of the fireplace. Squeeze the cans…. You toss ’em in the waste-basket, you belch three times and go to bed.” Ah, well. Prosaic realities aside, Bridges continues to inspire countless romantic daydreams. Couples have been flocking to Winterset to wed on the now-famous Roseman Bridge (see Box), and the Washington offices of National Geographic have been flooded with calls and letters from people frantic to track down the real Robert Kincaid (there isn’t one). Alan J. Pakula, who directed Streep in Sophie’s Choice, has a fantasy of another sort. “If there’s a heaven for directors, it would be to direct Meryl Streep your whole life,” he says. “And my wish for the world is that Meryl will [someday] be 90 years old, acting in a great role written about a 90-year-old woman.”

Posted on March 16th, 2025

|

Posted on February 24th, 2025

|

Posted on February 17th, 2025

|

Posted on February 15th, 2025

|

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|