|

Simply Streep is your premiere source on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her the praise to be one of the world's greatest working actresses. Created in 1999, we have built an extensive collection to discover Miss Streep's body of work through articles, photos and videos. Enjoy your stay.

|

|

Hope I Die Before I Get Old

Premiere ·

September 1992

· Written by Teresa Carpenter

|

|

Tags

|

“Ah, everyone please come forward,” urges the emcee. “Lisle will be down in a very few minutes.” From the wings of a great gothic balcony emerges Isabella Rosselini. She is nude. Not the drooping, full-figured nude of “Blue Velvet” but a lithe seminude swathed in a diaphanous black cape, nipples discreetly obscured by heavy necklaces and a flesh-colored adhesive called “soufflé”. “Look at yourselves! Just look at yourselves,” she exults, spreading her arms to acknowledge the applause. Below lies her handiwork: an expanse of some 400 beautiful people, bejeweled and outfitted in evening wear. Under the effects of her transforming elixir, not even the middle-aged among them betray to wrinkle or a liver spot. And standing in attendance upon the flaming enchantress are two familiar figures gowned in black, as animated as if they were exhibits in a wax museum: Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn. But their lips are too red, their fingernails too pointed. There is a spooky perfection here that suggests a coming-out party for Morticia Adams. It is, in fact, a scene from “Death Becomes Her”, an epic tale of vanity and vengeance that director Robert Zemeckis allows is “probably the most lavish black comedy ever made in the history of the world.” There was a time when mentioning the word “lavish” and “black comedy” in the same breath would make a studio executive hyperventilate. Pariahs of the movie industry, gleefully ghoulish films such as “Harold and Maude” and “Eating Raoul” were made on a shoestring and ended up appealing to a narrow band of iconoclasts on college campuses. All that changed in the late ’80s, when such films as “Beetlejuice” invaded multiplexes, making converts of a generation of mall rats. Freddy Krueger played horror for laughs, “Throw Mamma from the Train” demonstrated that not even motherhood was immune to impiety, and the recent success of “The Addams Family” firmly established black comedy as the genre du jour.

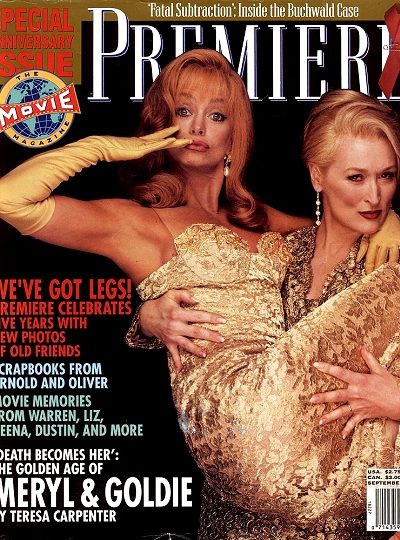

Universal Pictures’ leap into the black, the studio hopes, will be just that. “Lavish” to the tune of $40 million-plus, “Death” boasts not only Streep, Hawn and Bruce Willis but an ensemble of supporting actors including Rosselini and Tracey Ullman. A director’s dream cast has been married to a studio’s dream director, Bob Zemeckis, who packed theaters with “Who Framed Roger Rabbit” and the “Back to the Future” series. The film, furthermore, offers a timely message: in telling the story of two middle-aged beauties who resort their ruthless means to keep their looks, “Death” is calculated to appeal to a generation of baby boomers in search for eternal youth. “Death” defies each synopsis. (“I’ve never made a film that you could describe in a sentence,” Zemeckis says with pride.) Hawn’s Helen Sharp is a brainy book editor who’s engaged to Ernest Menville (Willis), a weak-willed plastic surgeon. Then Streep’s Madeline Ashton, a Hollywood actress whose beauty and career are on the skids, steals Ernest from her old school chum. Their marriage drives the doctor to drink and subsequent ruin, so that the only work he can get is at a mortuary refurbishing corpses. Meanwhile Madeline tries to salvage her remaining youth with “plasma separations” and “collagen buffs,” and Helen suffers a breakdown – emerging with a plan to murder her old rival and win back Ernest. She becomes the writer of a successful beauty book and engages in a make-over that causes her to look younger than Madeline. In a demented game of one-upmanship, both Madeline and Helen resort to the supernatural, with dire consequences. Although the moral of this tale if that it’s not nice to mess with “the natural law”, the film’s real focus is watching “Mad” and “Hell”, as they refer to each other with acidic affection, alternately age and grow younger, literally tearing each other apart, always to be stitched back together by the hapless Ernest. “It’s about people who are wrong,” says Streep. “All of them are wrong. And the further I go with her obsession to restore her beauty, the more realistic it becomes and sort of trafic and funny. That’s what I find playing it – and that’s fun.” Could such a topical, star-sudded project flop? Of course. It could be swept like some glittering piece of flotsam under a tital wave of summer sequels. Or it could simply fail to find its audience. Although “The War of the Roses”, Danny De Vito’s dark tour divorce, attracted mature moviegoers, black comedy’s biggest draw is for those between the ages of 12 and 24, a crowd that has not yet begun to ponder its mortality. Each of the names in this production presumably brings to the opening his or her own following, but it may not be precisely the right following. “You have to take what’s good when it’s around,” says Streep. “So I was very interested in doing it. Assuming of course, that they wanted me to play Helen.” Why? “He told me they wanted me and Goldie for these parts. The thing opens with Madeline doing a song-and-dance routine on Broadway – I assumed that was Goldie. Helen’s part was the manor born, Upper East Side – the part I thought they would cast me in. When they told me that I was going to be Madeline, I was very exited.”

In between setups, Streep lounges in a director’s chair with her name stenciled on the back in Gothic letters. Her black off-the-shoulder evening gown with its daring décolletage is what the costume designer calls “rich, stylized Beverly Hills.” A long blond mane frames her famous oval face. Even up close, she looks unnaturally good, patricularly considering that she is 42 and the mother of four. The light of a chandelier right above her hits her upturned face, revealing for a moment the only visible sign of agin: ultrafine lines around her eyes. They are to ordinary crow’s feet what angel hair is to fettucinin – and they have a graceful upward sweep. The irony could certainly not have escaped her: a middle-aged actress playing a middle-aged actress obsessed with youth and beauty. Asked if it was this congruity that drew her to the project, her answer is a firm no. “I mean, no. No. It’s a synchronicity of events. What drew me to it was that it was funny and it was good. I liked its little issues. To me, actresses are people who are most obviously valued for their physical beauty. It’s sort of a hyperbolic example of what everybody experiences.” Has she ever had plastic surgery or contemplated any of the cosmetic excesses in which Madeline engages? “Well, I’ve had…” she gestures to her temples but then draws back, “braces and things.” She thinks. “I considered having a nose job. I had a big nose when I was little. When I was teenager, the idea was to look like-” She thinks harder. “Who was the model? – Jean Shrimpton. I was ordered by this company to get a trainer; I just had a baby, so they had reason to worry about my midsection. I don’t normally do that,” she says, sighing operatically. “Life’s too short.” In the past, Streep has been outspoken about the shabby way the movie industry treats women. In response to statistics released in 1990 indicating that more than 70 percent of all film roles went to men – and only 9 percent of all film and TV roles went to women 40 and over – she predicted, as keynote speaker at SAG’s first National Women’s Conference, that “in twenty years, we will have been eliminated from movies entirely.” Nowadays she’s taking a softer line. “I made one speech to a gathering, and at that time, things were pretty bleak. But everything changes,” she explains. “It’s pretty liquid.” Cases in point: “Thelma & Louise”, “Fried Green Tomates” and “The Grifters.” Streep’s own career has been pretty liquid of late. In fact, one might say it’s gone through a sea change. At the time she made her militant pronouncement to SAG, Streep was a much-honored, albeit frustrated, star. Her infinite mutability and array of accents garnered her two Academy Awards and almost annual nominations. She is hailed as “our greatest living actress”. National treasure or no, Streep still cannot open a film. Although she has denied making any conscious decision to go commerical, her actions belie in her words. The galvanizing episode reportedly occured when Mike Nichols, who had directed Streep in three films, was making preliminary casting choices for “Remains of the Day” and passed over her. Streep left her longtime agent, ICM’s Sam Cohn, and moved to CAA, while relocating her family from Connecticut to Los Angeles. Her last three films have been comedies that offered the hope for a commercial breakthrough: “She-Devil”, opposite Roseanne Barr (now Roseanne Arnold), which flopped despite heroic efforts by Streep (“I think it meandered,” she says); “Defending Your Life”, with Albert Brooks, which flopped despite touching and hilarious performances by both actors (“I did Albert’s movie because Albert came and performed it beside the swimming pool. Wouldn’t even let me read the script”); and “Postcards from the Edge” with Shirley MacLaine, which was a modest hit. “To me, Postcards was a dramatic role,” she says. “It was a comedy, had smart lines, but it had a real basis in pain. But there are comedies and there are comedies. That’s not like this – this is wild.” “Death” offers Streep her best shot to date at the elusive breakthrough. Yet she downplays the signifiance of her presence here, characterizing it simply as a fun romp with her good friend Goldie.

“I love this movie because it appeals to my personal optimism,” Goldie Hawn is saying. “It certainly doesn’t seem like an optimistic movie, because it’s so black and so harsh. But the movie’s message in the end is so profound: about loving, sharing, enjoying your place on this earth, no matter what stage of life you’re in.” Hawn has doffed her own skinny black gown and relaxes in her street clothes. At 46, her face is more deeply lined that Streep’s, a distinction visible only at close range. She has, however, the body of a 22-year-old. There is an admirably equipped workout room in a tiny compartment at the end of her trailer. In contrast to her waifish screen persona, she is surprisingly earthy. And she is nettled about being condemned by popular demand to play comedy. Hawn recounts a conversation she once had with Bette Davis in which the aged actress described working under the old studio system. “I played six characters in one year,” Davis said. “Some of them I hated, and some of them I loved, but I was constantly greasing my instrument. And I was constantly being able to stretch who I was. You make one movie every two years. I don’t understand how you kinds get any bettaaah.” Hawn seems to have an earnest and touching desire to get betaaah. And to once, just once, be considered a serious actress. “Early on, I did films that were more dramatic.” Such as her character in “Cactus Flower?” She had her moments. “Shampoo” – she had her moments. Certainly “Sugarland Express” was a tragic character. Then there was “The Girl from Petrovka”, which five people saw – that was a Russian girl who had a very tragic end. But if people perceive you as being funny – making them feel happy, helping them transcend a state at the end of the day – they don’t want you to be different. “There was a story I heard the other day. This woman had seen comedy after comedy that I had done. And when she went to see “Deceived”, she cried. I thought she cried because the character was upsetting to her. But she cried because she thought she was going to see me funny. It was very hard for her to see this serious other person who most decidedly lives inside of me.” Hawn probably would not swap her box office appeal for Streep’s cachet, any more than Streep would swap her laurels for Hawn’s gross receipts. But each would clearly like a little of what the other’s got. Playing Hell to Streep’s Mad is definately an enchancement to Hawn’s career. It also presents the opportunity to “grease her instrument,” since the type of comedy required of her as a vixen from hell is a stretch beyond her usual string of bubbleheads. Both she and Streep have the satisfaction of playing against type and being paid well for it. When it comes to salaries, “you can go on about women and politics forever,” says Hawn. “We do get the short end of the stick. We are not paid equal amounts. But if the statistics prove that Mel Gibson with a gun is worth more than Goldie Hawn with a smile, then Mel Gibson is going to get more than Goldie Hawn. That’s a hard, cold fact – that’s business. But the truth of the matter is if you ask me, Goldie, it never bothered me. When I got a million dollars to make a movie, I said, ‘Don’t push for any more – I can’t believe I’m making a million dollars.’ Let’s face it,” she says, “we’re all wealthy – more wealthy than we’d ever though we’d be. We’re so wealthy, we’re trying to figure out how to raise our children normally so they don’t grow up with too much.”

Who got what is understandably a sensitive subject on this set, one that none of the principals want to discuss within earshot of each other. Basically, it comes down to this; the two divas got a minimum of $3 million apiece plus a percentage of the profits. (Streep has said she’s getting $4 million.) Turning industry practice on its head, the studio took a far tougher line in negotiating for a male lead. Several actors were originally considered for the role of Ernest, including Kevin Kline, whom Zemeckis felt had the “natural elements” for the role. That is, “he was a leading man and he could be funny.” The director, however, was irritated when Kline demanded to be paid the same as Streep and Hawn. “I don’t remember exactly what the numbers were,” says Zemeckis, “but he was asking for an outreagous percentage hike. Actors get a raise every time they make a movie; I don’t know why, but they do. When you ask for 50 to 100 percent more from one movie to the next, you say, ‘What planet are you living on?’ He was asking for what the women were getting, and I didn’t feel I should give him a million-dollar raise just because it’s a big movie and I’m the director. But we should talk about Bruce, because he’s the guy who’s making this happen.” Zemeckis can afford to be sanguine about Willis, who leaped into the void, agreeing to work for scale and a percentage of the gross. The director, in fact, is extravagant in his praise. “The thing about Bruce is that he acts; he’s not typecast here. He’s this good looking, well-built, strong guy who acts this weak character – to me, that’s the whole point of acting, not to be yourself. You can’t just put anybody in the middle of these two women and think they’re gonna hold their own. Even under all that makeup, he holds the screen.” Willis’ reputation for moodiness and arrogance had the costars wary. “Nobody writes anything nice about him,” says Streep. “I walk into a situation like this with a little trepidation because everything you’ve ever read about him is negative. I guess it’s like being someone who defends Nixon, but I really like him. I mean, the guy’s gotten a bum rap as far as I’m concerned. He’s been a dreamboat on this one, coming in all loaded and ready and eager. I think he’s doing a great job of it, too.” She tells of how one day she and Hawn were standing around “gossiping or something” and Willis approached them. “He had this serious face and I though, ‘Uh-uh.’ I though he was going to say, ‘This is so fucked up.’ But he said, ‘You know, this if the most fun I’ve had in seven years, and it’s because of you girls.'” Done over in dishwater-blond hair, mustache and glasses, the 36-years-old Willis appears harmless to the point of mousy. The costume designer’s name for this look is “dishelved Brooks Brothers.” Willis is not carrying the film on his back, so if it fails, no one can blame him. If it succeeds, however, the swelling tide will lift his boat as well. And he goes out his way to be accommodating. As he rehearses his exit from the ballroom, he takes direction with humility. Asked to back into a scene, he replies, “We used to do it different on TV, but I like it better this way.” His congeniality extens even to the media. Spotting a Good Morning America personality, he croons, “Chantal. Hi, sweetheart. Am I gonna talk to you today?” “Bruce, darling,” she countercroons. “I love you more than air.” Willis confirms that his experience has been a happy one. “There’s a lot of confidence in the script. It allows us to focus on comedy – which is harder than anything. It’s such a problem-free, ego-free set,” he says. “We’ve laughed a lot during this film. At the same time, it’s a very professional atmosphere. He’s a really great director.”

Virtually everyone who’s worked with Zemeckis would agree that he is one of the sanest directors in Hollywood. He projects a confidence that is infectious. “There are directors who are screamers, who are so upsetting to be around, you don’t wanna be there,” says Hawn. “Bob is easygoing. He’s quiet. He’s a man of few words. He doesn’t need to flutter. It’s great for actors to be around someone like that, because it calms the stable.” “There is no sloposis,” concurs Streep. “He’s decivice, he’s clear.” This clarity, insists producer Starkey is due to Zemecki’s ability to previsualize scenes so that they can be shot exactly as they were commited to storyboards. Working from precise blueprints, all departments know when they come to work in the morning exactly what props and equipment will be required. Furthermore, Zemeckis tries to use the same crew from film to film. Several of the old guard were previously commited to the “Batman” sequel, but he managed to assemble key personnel, including Starkey, co-producer Joan Bradshaw, director of photography Dean Cundey, costume designer Joanna Johnston, composer Alan Silvestri, production designer Rick Cater, and film editor Arthur Schmidt. One of Zemeckis’s most admirable skills, say his cohorts, is an ability to take a rough script and systematically eliminate lapses in tone or logic that can cause expensive delays if there have to be worked out on the set. Weeks before commencing principal photography, the director sat down with the screenwriters and cast to iron out the glitches. “Bob is a writer himself,” says an admiring Koepp. “But he puts his ego aside. You don’t feel bad about contributing even a bad idea.” It was during one of these story meetings that Hawn argued successfully for the addition of two new scenes dramatizing Helen’s deterioration after she’s jilted. One of these shows her consuming tins of vanilla cake frosting as she balloons up to 250 pounds, an innovation that required the construction of a “fat suit” and, for her breats and buttock region, the use of a quivering urethane rubber called Flabbercast. Hawn’s insistence on the fat scenes had the effect of elevating the role closer to the level of Streep’s. But, Zemeckis insists, his actresses never stopped to petty ego games like counting lines”. The general goodwill that prevailed during the shooting of “Death” will go a long way to dispel the notion that Zemeckis is just a director of Toons. He took on a potentially fierce set of egos and reduced them to purring pussycats; his actresses sat around giggling and knitting, watching their children cavort about the set as if it were a huge Gothic playground. “Goldie makes me laugh and I make her laugh, and they say, ‘Let’s go again,'” says Streep. “I’m somewhat less disciplined when I work with her.” If Zemeckis is impressed with this coup, he does not sow it. Asked if Toons are easier to handle than actors, he replies without irony: “No, the Toons are much harder. When you have a live actor and you give ’em your direction, they immediately do it and you can see if your instincts were right or not. But a Toon takes, like, a year. So you have to think, ‘Well, let’s have the rabbits do this’ and four months and hundreds of thousands of dollars later, you hope you were right.”

Listening to Zemeckis discuss the relative merits of actors and Toons, it’s hard not to be struck by the fact that hey seem to occupy nearly equal weight in his personal cosmology. Zemeckis, it seems, is in awe of nothing but The Desired Effect – and one gets the feeling that if disassembling actors and recombining their parts would chance The Effect, he would probably jump at the chance. In fact, he comes very close to doing just that. Much of the plot development and comedy in “Death” derives from the character’s physical malleability, achieved through state-of-the-art technology. It is no secret that special effects are Zemeckis’s great love, and he approaches them with the glee of a child inventor puttering in his laboratory. Koepp, who agreed to alter the script to accommodate more of the director’s high-tech innovations, ecalls one episode where he, Donovan, and Zemeckis were discussing a scene in which Madeline falls down a staircase, causing her head to turn 180 degrees on her shoulders. In the original script, she sat up, twisted her head straight, and proceeded to the next scene. Zemeckis thought it was funnier if she were in that scene with her head on backwards. “Is that possible?” asked one of the writers. Zemeckis grinned and said, “I don’t think so.” “You can see his eyes light up,” says Koepp, “if he thinks he is doing something that hasn’t been done before.” The scene, eventually executed to everyone’s satisfaction, required Streep to walk through her paces backward, her head covered with a blue hood and her neck in a prosthesis, and then repeat it facing forward, this time sitting with her head bared against a blue screen. The image of her head was then reattached to her boy and the prosthetics replaced by a computer-generated graphic made it look like a twisted neck. Finally, computer-graphics artists smoothed out the crude spots with technique analogous to a photo touch-up, only in three dimensions. Some of the film’s most difficult technical problems dealt with aging the characters realistically, then throwing the process into reserve. Two months before the start of principal photography, the actors came in for face casts. “It’s sort of horrifying,” says Streep, “because you’ve got to be encased in this stuff that gradually both heats and hardens. They put little things that you can breathe through, but you can’t open your mouth; it’s like being encased in cement. You have to stay still for twenty minutes.” She shudders. “Twenty minutes is a very long time.” Working with the resulting clay models, prosthetics makeup supervisor Kevin Haney experimented with creases and wattles that would advance the actors to the desired age, where the jawline sags – but only a little. “They kept making me look 70,” complains Streep, “and it’s gotta be 54.” In one scene, the middle-aged Madeline is restored to youth after imbibing a potion given her by Isabella Rosselini’s character, Lisle. She catches a glimpse of herself in a mirror and watches, astonished, as her wrinkles disappear. The process, called morphing, was used in “Terminator 2: Judgement Day” to effect the cyborg’s transition from metallic to human form. Morphing from flesh to flesh, explains producer Starkey, is a more difficult feat, since the human eye is less forgiving of inconsistencies in the gradual evolution of skin texture. This effect was achieved by first photographing Streep in front of the mirror wearing her wattles, then photographing her in the identical position without them. The two images were then entered into a computer, which digitized both, merging them in seamless metamorphosis from old to young. “That’s what the computer paints,” says Starkey. “She looks down. You see her butt lift up. You see her boobs get perky. She says, ‘I’m a girl'” The budget for special effects, originally estimated at about $4 million, reportedly exceeded that amound by some $500.000, the overage laid to the addition of new scenes. This figure may by somewhat conservatice in that it does not take into account such incidentals as $25,000 spent on Hawn’s fat-suit and another half a million or so to build and operate eight remote-controlled puppets that served as body doubles for the actresses during their most violent scenes. Also, at the last moment, Zemeckis concluded that the film’s finale was too sentimental. So another ending, which the director and studio executives considered more in keeping with the film’s harsh lunacy, had to be shot. This required that the principals be called back, the crew reassembled, new sets constructed, and more puppets built, adding just under a million to production costs. “Bob’s pretty fast,” confided one participant in this eleventh-hour mania, “but he’s going out of his mind”.

So what is the result of this costly confluence of digital alchemy and pricey talent? In the words of an enthusiastic Goldie Hawn, a movie that’s going to be a great one to go to have coffee afterward. Because everybody’s going to have a point of view, everybody’s going to argue.” The chatter in these late-night coffee klatches will presumably center on thorny issues of aging: How vain is too vain? What would you do to keep your looks? But beyond it’s “little issues”, “Death Becomes Her”, says Hawn, “is black and weird and outreagous. Really and truly, this movie is going to be a blast of a night.” The question remains, for whom? What is the likely audience for this dark and unquestionably lavish production? Baby boomers? Mall rats? All of the above? “In a perfect world?” Zemeckis asks rhetorically. “It would be great is everybody over thirteen wanted to see this movie.” As a practical matter, he knows he is not going to get the teens who go to see “Batman Returns” five times. “Only kids do that. We definately had that on ‘Back to the Future’. But we had a lot of old people going to ‘Back to the Future.'” He catches himself. “When I mean old,” he pauses to explain. “I mean over eighteen.”

Posted on March 16th, 2025

|

Posted on February 24th, 2025

|

Posted on February 17th, 2025

|

Posted on February 15th, 2025

|

Posted on November 17th, 2024

|