|

Simply Streep is your premiere online resource on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her acclaim to be one of the world's greatest living actresses. Created in 1999, Simply Streep has built an extensive collection over the past 25 years to discover Miss Streep's body of work through thousands of photographs, articles and video clips. Enjoy your stay and check back soon.

|

|

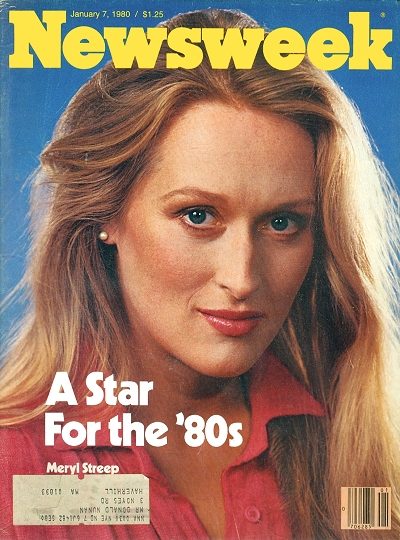

A Star for the '80s

Newsweek ·

January 1980

· Written by Jack Roll

| ||

|

Tags

|

The face is beautiful but anguished, haunted sorrow, despair, determination and love. Can one face express all these warring emotions, with a grave dignity that adds a deeper beauty to the physical structure? Meryl’s face can and does in the extraordinary first image of “Kramer vs. Kramer”. This first shot of a superbly crafted film prints indelibly upon the eyes and consciousness of the audience the face of a young actress who, at 30, may become the strongest performer of her generation, first American woman since Jane Fonda to rival the power, versatility and impact of such male stars as Dustin Hoffman, Robert De Niro and Al Pacino. Hoffman plays the male lead in Robert Benton’s moving film about the struggle of a divorced couple for custody of their 6-year-old son. And the instant success of “Kramer vs. Kramer” is due largely to the superb performances of Hoffman and Streep, who have already been cited by both the New York and Los Angeles film critics as best actor and best supporting actress. They seem to be odds-on favorites to win Academy Awards, as does the film itself, which was voted best picture by both critics groups.

The supporting-actress category is in a sense a technically. Hoffman and Streep are the antagonists in “Kramer vs. Kramer,” although the film’s boldly effective dramatic structure focuses on Streep at the beginning and in the latter part, while Hoffman dominated the middle. The compelling face in that first shot belongs to Joanna Kramer who, driven by an inner crisis of identity, is leaving her husband Ted and son Billy. Although most people will have a built-in aversion to the sight of a woman abandoning her child, the complexity, clarity and power of Streep’s acting forestalls that reaction. Writer-director Benton cuts instantly to the nerve of the matter, forsaking plot exposition for the stark, electric fact of a marriage suddenly breaking up, to the amazement and confusion of Ted, who hasn’t had a clue that anything is wrong.

What’s wrong, in fact, is neither Joanna nor Ted, and this is one of the great merrits of the film. What’s wrong is the marriage itself and it forces, both social and psychological, that have made abberant human beings out of both husband and wife. Ted Kramer is a hot-shot advertising man on his way up in a business that demands an appaling dedication of energy and time. “It’s 25 hours a day, eight days a weel,” he tells his boss, who’s just handed him a promotion. From “The Hucksters” on, we’ve seen this world again and again in films, but never with such sharpness of details and tragicomic force. In a beautifully paced cresendo of scenes, we now watch the funny and appaling spectacle of Ted trying to fulfill the imperatives of Madison Avenue and bring up his son at the same time. The acting of Hoffman and little Justin Henry as Billy is screen acting at its best, beginning with a hilarious but devastating breakfast scene in which Ted’s attempt to make French toast for Billy, all the while cherring himself on with a play-by-play commentary, results in a clattering, splattering chaos.

This is a movie about change, and there’s a real excitement in watching the decent, frazzled Ted try to become a double parent to his little boy. It’s impossible not to be moves as their relationship passes trough one crisis after another. In a marvelously played pivotal scene, Billy challenges Ted’s authority by passing up his dinner to eat cholocate-chip ice cream. The resulting explosion leads to a deeper understanding between father and son. If it sounds corny, it’s not: Benton is able to get a deep human resonance out of the most mundane domestic details.

What we’re watching is an initiation rite: nearly 40, Ted Kramer is growing up. Some critics have caviled that Ted is too good to be true, but “Kramer vs. Kramer” wants to show how decency can struggle to fruition under grievous pressure, and why shouldn’t we welcome such an intelligent and sensitive attempt to shape such a vision out of ordinary lives? The endemic lack of decency that the world seems to flaunt every day has gotten to be a damnable bore: Ted and Billy’s struggle toward a by no means simple love isn’t sentimental; it’s kind of thrilling. We can believe Ted’s growing insight, achieved by the free excercise of his intelligence, intro Joanna’s problem. Trying to explain her absence to Billy, he says: “I tried to make her a certain kind of person.. I wouldn’t listen… Just because I was happy I thought that meant she was happy, too.”

Ted’s good faith is tested when Joanna returns after eighteen months to claim custody of Billy. In the climatic courtroom sequence, the film finally becomes Kramer vs. Kramer. The masterstroke is to show the adversary relationship as complicated by the new feelings of understanding and compassion that now divorced pair have for each other. As their lawyers examine and cross-examine, ttrying to break down the character of both parties, Ted and Joanna try to transmit their new understanding of each other even as they fight for the child. In evoking the absurdity and pain of this double bind, the acting of Hoffman and Streep reaches a peak of emotional power and an orchestration of detail that from any point of view must be seen as masterly. Some have called the writing slick and soap-operatic. But actually the screenplay, a collaborative venture in which Benton’s script, based on Avery Corman’s novel, was altered significantly by both Hoffman and Streep, is an excellent example of shrewdly simple means that succeed in touching hearts, minds and nerves. Tears will very likely well up in you: notice how well-earned they are, and notice that the writing is a kind of choreographic “score” that’s embodied with grace and power by Hoffman and Streep. There are many wonderfully effective scenes. Ted racing Billy to the hospital after a playground fall and comforting him as he receives hair-raisingly real stitches near his eye; Ted saying with supernal sorrow, “Shame on you,” when his boss fires him at lunch; a perfectly calibrated scene in which a girl (Jobeth Williams) whom Ted has just slept with encounters Billy on her way, naked, to the bathroom. William’s adorable comic embarrassment typifies the work of a superb supporting cast: Jane Alexander as a neighbour who tries to be a friend to both Ted and Joanna, George Coe as the heartless boss, Howard Duff as Ted’s lawyer – a marvelous vignette of a florid, elegant hard-drinking Irishman who has both true tenderness and a courtroom killer instinct.

Because of “Kramer vs. Kramer” hits so close to home, people care about its “truth” in a personal way. Lawyers and judges spezialising in child-custoy cases were interviewed by The New York Times and found the movie’s custody trial unrealistic: in the film, the judge doesn’t interview the child; he doesn’t appoint a psychatrist or neutral expert. In Ms. Magazine, which can be taken to reflect mainstream feminism, Barbara Grizzuti Harrison wrote that she “rooted for the father, laughing and crying all the way,” but later thought that she had been manipulated in a way “not immediately easy to analyze” by the filmmakers. Some critics have wondered why Ted never gets a baby-sitter or housekeeper. Benton actually filmed some scenes showing Ted interviewing housekeepers, but didn’t like them and simply cut them. This may sound cavalier, but essentially Benton was right. These details are the worst minor flaws. “Kramer vs. Kramer” is really about two middle-class people who find that they are trapped in false lives and try to relearn their humanity. It’s the emotional texture of the film that’s important, and that registers superbly, thanks chiefly to the inspired acting of its leads. Even the legal experts cited in the Times admired “the beauty of Meryl Streep’s performance.”

That makes it unanimous. In only her fifth film, Streep has made a stunning impact on audiences and on her fellow professionals. Last year, she won an Oscar nomination for “The Deer Hunter” as the steel-town girlfriend of one of the soldiers who goes off to the horror of Vietnam. This past year she has graced three films: in Woody Allen’s “Manhattan”, she played Woody Allen’s ex-wife who’s become a lesbian; in “The Seduction of Joe Tynan,” she played opposite Alan Alda as the tough-minded attorney having an affair with a married senator who’s running for President. And now “Kramer.” With her striking offbeat blond beauty, her extensive stage background, which reaches from Shakespeare to Chekhov to the leading young American playwrights, Streep has impressed just about everyone as something new among recent American actressesm a combination of sensuous appeal and high intelligence that seems almost too good to be true. With Streep, thinking and feeling are locked in a perpetual embrace. When she was working on the character of Joanna, she hung around the playgrounds of New York’s Upper East Side, watching the young mothers with their children while their husbands were at work. “The more I thought about it,” she says, “the more I felt the sensual reason for Joanna’s leaving, the emotional reasons, the ones that aren’t attached to logic. Joanna’s daddy took care of her. Her college took care of her. Then Ted took care of her. Suddenly she just felt incapable of caring for herself.” Streep’s insight into Joanna is a feeling for someone the exact opposite of herself. “I wanted to play a woman who had this feeling of incapability, because I’ve always felt that I can do anything.”

There’s no arrogance when Meryl says this – only a bemused irony at the confidence and good fortune that have always attended her. But those who work with her say the same thing, and there’s no irony, only amazement. Jerry Schatzberg, who directed Streep in “The Seduction of Joe Tynan,” says, “She is going to be the next major American actress to be offered everything. She can do anything she wants to.” “I think I have a romantic concept of Meryl,” says Robert Benton. “I have surpreme faith in her. She can literally do anything.”

Oddly, the first choice for the role of Joanna Kramer wasn’t Streep but Kate Jackson, the former Charlie’s Angel. Meryl was interviewed for the two-scene role of Phyllis, Ted Kramer’s one-night stand who bumps into Billy in the buff. Benton, Hoffman and producer Stanley Jaffe met her at a New York hotel. When she left, Hoffman and Benton looked at each other and said, “She’s perfect. She is Joanna.” Although Benton, Hoffman and Jaffe knew Streep’s stage work, she was hardly a major movie figure with “The Deer Hunter” and “Joe Tynan” finished but not yet released. Still, Meryl had strong ideas about reshaping Joanna so she would be a more sympathetic character. Dissatisfied with Joanna’s long courtroom speech, Benton suggested that she rewrite it – an promptly forgot the suggestion. When he started filming the courtroom scene, Meryl arrived with the speech she had rewritten. “I thought, oh my God,” recalls Benton, “I’m going to lose two days’ work. One, rewriting what she’s done and the other soothing her wounded feelings. Well, her scene was brilliant. I cut only two lines. What you see there is hers.” Watching Meryl in that scene, says Benton, “it was as though someone set off an enormous bomb. Meryl devastated us. We shot her testimony in eight or ten takes – close-up, medium shot, long shot. She stayed at the same level all day long. We even did one take with the camera on Dustin for his reaction. The whole crew had its back to Meryl. When it was finished we turned around and there was Meryl in tears. She’d given it that much all over again, and just for a reaction shot.”

Hoffman, who has been known to be difficult on a set, got along well with Streep except during the restaurant scene where she announces she will seek custody of the boy. Meryl wanted to break the news late in the conversation instead of the beginning, as the scene was written. While time and money melted away, Hoffman and Streep argued. “I hated her guts,” recalls Hoffman. “But I respected her. She’s ultimately not fighting for herself, but for the scene. She sticks with her guns and doesn’t let anyone mess with her when she thinks she’s right.” The scene was rewritten Meryl’s way. Now Hoffman sounds just as smitten with her as Benton. “She’ll work twenty hours a day,” he says. “She’s an ox when it comes to acting. She eats work for breakfast.” But the ox can move. “I loved acting with her. It’s like playing with Billy Jean King. She keeps trying to hit the perfect ball. And,” he adds, “although it sounds chauvinisitc, Meryl is never at the mirror between hots, like a lot of actresses are. She’s in the script, she’s in your ear, saying why don’t we try this or that? She’s not going back to check her face. The early Meryl Streep was much more narcissistic. Born Mary Louise Streep (the name is of Dutch origin) in a middle-class suburb in New Yersey, she was called Meryl from birth by her mother, who simply liked the name. Meryl traces her development from an “ugly little kid with a big mouth, an obnoxious showoff” who bossed her two younger brothers around, to a bright kid who was good about almost anything but serious about nothing. Certainly not about the theater, and not about singing, even though at 12 she had a beautiful voice and was a protégée of Estelle Liebling, the celebrated teacher of Beveryl Sills, among others. After a brief but feverish outburst of conventionality in high school, where she became a cheerleader and plunged “very heavy into the boy scene,” she went on to Vassar, where she resumed her activites as a “jack-of-all-trades, master of none.” She even resisted the counter-culture fever of the 60’s, except for some “half-assed guerilla theater.” But she was turned off by the big anti-this, pro-that campus bonfire rallies, mot of which were led by men students who were then making Vassar coed. “I saw people who, in class, had given interesting opinions on important things caught up in the mass hysteria, a mad glaze over their eyes. I know how powerful this was essentially theater – but the wrong kind.” So Meryl got into the right kind at Vassar, winning the lead in Strindberg’s “Miss Julie” from more experienced actresses and collecting raves.

“Miss Julie” was not only the first serious thing Streep did as an actress, it was the first serious play she had ever seen. She thought it was great fun, but “still didn’t want to be an actress. I still didn’t think it was a legitimate way to carry on your life.” Spending part of her senior year in a theater program at Dartmouth didn’t change her mind, nor did a subsequent season with with a Vermont theater group that tried to bring Checkov to local snow bunnies at the ski resorts. Then she applied to two distinguished professional schools, Juilliard and the Yale School of Drama. “Juilliard had this very uppity, expensive application that finally added up to $50. Yale’s application was $15 and I was making $48 a week. So I wrote Juilliard a snotty letter saying this just shows what kind of cross-section of the population you get at your school. I applied to Yale and I got in and they gave me a scholarship. At Yale she became something of a legend. In three years she played about 40 party, everything from the Salvation Army lass in the Brecht-Weill musical “Happy End” to a young lover in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” to a decayed ancient in “The Idiot Karamazov,” a madcap burlesque by two bright and brash young playwrights, Albert Innaurato and Christopher Durang. This was the most schizophremic phase of her life. Under Robert Brustein, Yale had developed a powerful training program and a venturesome repertory theater, but Streep still swung between creative elation and a nagging sense of “the absurdity” of theater as a way of life. She didn’t like being whipsawed by a constant barrage of master teachers, each of whom would preach the one true way until he’d be fired and another guru would come in. “That kind of grab-bag, eclectic education is invaluable,” says Streep, “but out of adversity. Half the time you’re thinking I wouldn’t do it that way, this guy is full of crap, but in a way, that’s how you build up what you do believe in.” What she did like was “the fun of it, the collective electricity. That was a secret that none of them with all their methods could take away from me.” Streep’s idea of fun was pure creativity. Joe Grifasi, a gifted comic actor ho was a fellow Yale student, remembers one time when an actor missed a cue and Meryl was left alone onstage for several minutes. “The setting was a psychiatrist’s office,” he says, “and Meryl walked around, picked up some objects and finally perring intently at the Rorschbach inkblot pictures on the wall. Then she looked at the audience as is she had discovered a major law in her character and burst into tears.”

This instant creativity was instantly noticed by Joseph Papp who, after her graduation from Yale, hired Streep to play a small part in Pinero’s late Victorian comedy, “Trelawney of the Wells.” Papp flatly calls her the most remarkable actress that he’s had at the Public Theater. “There are only a few people around I would call pure actors,” he says. “Meryl is one. That means that the entire body is an instrument that is used constantly to serve a particular character. You can see it in her face. I’ve seen her cheeks get red, so that you can see the internal thing through her skin, which means that there’s a total emotional involvement in the situation. And she takes tremendous risks, both physical and emotional. I thought she was going to break every bone in her body when she threw herself on the floor playing Kate in “The Taming of the Shrew.” And there are certain actors who would never play a negative role because they fear that the audience would not like them. But Meryl doesn’t care and she violates her classic beauty constantly.” There are those who are put off by all this adulation of an actress who’s had such a short career in the public eye. Three years at Yale, three more acting in the Northeast are at theaters like Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival, Arcin Brown’s Long Wharf Theater in New York, a couple of TV shows, notably her Emmy-winning performance as a Catholic married to a Jew in “Holocaust,” five movies – what is there about Streep that triggers such universal admiration? And where is her hidden flaw? People sense there’s nothing new about Streep. There’s a sense of mystery in her acting; she doesn’t simply imitate (altough she’s a great mimic in private). She transmits a sense of danger, a primal unease lying just below the surface of normal behavior. A Streep character isn’t quiete sure who she is or exactly what she’s doing – just like you and me. She’s less ingratiating than Jill Clayburgh, less self-satisfied than Jane Fona (not the Fonda of “Klute”). An unline the Great Bimbos of the 70’s, the Farrahs and Suzannes, her beauty has nothing to do with the yearning smirks of male fantasy. Farrah smiles like a plastic nutcracker; Streep smiles like destiny.

As for her hidden flaw, well it seems to be a hidden pretty well. “I can’t think of anything bad to say about Meryl,” says James Woods, her co-star in “Holocaust,” “and I love to say bad things about people.” Nothing bad, but sorrow, yes. Meryl lived with John Cazale (the fine young actor remembered by most people for his portrayal of Fredo, the weak son in “The Godfather”) until his tragic death of cancer in 1978. A few weeks later she had to film “The Seduction of Joe Tynan.” The actor John Lithgow recalls that she had to do a love scene in bed with Alan Alda. “It’s a scene that demands tremendous high spirits and a great deal of sexual energy,” says Lithgow, “and at that time, right after John Cazale had dies, Meryl was in no mood for either. And she was embarrassed by the scene. She said she would perspire until she was dripping wet from embarrassment.” Alda remembers the incident as an ordeal for Meryl. “She looked at the movie,” he says, “as some kind of test, a test she had to pass. She was determined not to buckle.” The man who helped her through this difficult time was Don Gummer, a 32-year-old sculptor who was a friend of Meryl’s brother Harry III, who is a modern dancer and choreographer and who’s known as Third. Meryl and Don were married in September 1978, and this past November she had her first child, Henry. They live in Don’s loft on lower Broadyway, modest premises for the coming star of the ’80s, but just right for Mr. and Mrs. Don Gummer. They don’t travel in the febrile, vampire-fanged purlieus of showbiz; most of their friends are young artists or actors. The Gummers send forth waves of sanity and happiness. He is strong, quiet type whose open, ordered, geometric sculpture reflects those qualities. Each has benefited from contact with the other’s art. “She’s learned how to look at objects and I’ve learned who to look at people,” says Gummer. Understandably sensitive about being married to a potential superstar, he has no fears for their relationship. “There are many different levels of love,” he says. “Ours is founded on a very deep-rooted feeling of trust. We’re best friends.”

Streep has entered the crucial phase of her career. The pressures and pitfalls of stardom are gathering around her. Producers like Alan Ladd Jr. and Allan Carr rate Streep in the §350,000 – $540,000 category right now, not “bankable” like a Streisand or an Eastwood. But, says Carr, “She’s a bargain in comparison to other actresses who get a million and don’t draw any more than she does. Any leading man looks better by being with her. She gives any ordinary picture a major stature.” This is the bottom-line talk of gimlet-eyed moneymen. Streep is determined to resist their blandishments; she doesn’t want to give ordinary pictures major stature; she wants do so serious and exciting work. She wants to be a screen actress, a stage former, a wife, a mother and anything else that will bring together life and art into civilized fashion. Because of her beauty, she’s constantly brushing aside feelers of movies like “Sidney Sheldon’s Bloodline” or Judith Krantz’d “Scruples”. On the other hand, she was eager to do a remake of the old Lana Turner movie “The Postman always Rings Twice,” which has a promising screenplay and some explicit sex. Streep was willing to play the sex scenes as long as co-star Jack Nicholson would be as visibly explicit as she. The producers gave the part to Jessica Lange. Can a stunning, smart, serious young actress who can play everything can find success in the chrome-plate Disposall known as the movie-industry? Michael Cimino, who directed Streep in “The Deer Hunter”, thinks she’s going to be dominant figure of the 80’s. Dustin Hoffman says, “She has an incredible piece of working life ahead of her. She’s going to be the Eleanor Roosevelt of acting.” But Joe Papp is worried. “Hollywood,” he says, “looks for a quality and they try to exploit that quality. You can’t do that with her because she has too many variables – you can’t stamp out cookies with Meryl. I just hope that there are good enough roles for her to play in the movies, which are still a male medium. I have a feeling she’s going to run into a lot of frustration. Meryl is still an oddball in the movie industry, no matter how interesting and complex she is. She’s too good an actress, and I don’t think she can compromise even if she wanted to. That’s the greatest saving grace she has.” Streep says: “I feel pulled in a lot of different directions but I haven’t shattered yet. I feel that I’ve made commitments professionally, to my marriage, to my baby, to the community.” By community she means “the community of souls, whatever we all are collectively.” She says things like that the way other people talk about the kitchen sink. For her such things are the kitchen sink, they’re reality. “Everyone should put their life on the line according to their art, because everything else is easy,” she says. “Zero Mostel, for example, there’s a man who put his life on the line for comedy, for making people laugh. I see myself acting forever and ever and ever. But I’m not interested in lazy drama or lazy movies that say ‘Well, let’s just go this high; OK we got that high, people will love it’.” How high will Meryl Streep go?

Jack Roll with James N. Baker and Constante Gutherie in New York, Martin Kasindorf and Janet Huck in Los Angeles

Posted on September 16th, 2025

|

Posted on September 9th, 2025

|

Posted on August 12th, 2025

|

Posted on June 13th, 2025

|

Posted on May 18th, 2025

|