|

Simply Streep is your premiere online resource on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her acclaim to be one of the world's greatest living actresses. Created in 1999, Simply Streep has built an extensive collection over the past 25 years to discover Miss Streep's body of work through thousands of photographs, articles and video clips. Enjoy your stay and check back soon.

|

From her first days in power, Margaret Thatcher developed and refined ways of circumventing political protocol and procedure. Serving three consecutive terms in office until 1991, Thatcher remains one of the dominant political figures of 20th century Britain- and one of the most controversal in history. Her life and career was portrayed in fragments and flashbacks by Meryl Streep in “The Iron Lady”.

Margaret Hilda Roberts was born on 13 October 1925 in Grantham, Lincolnshire, the daughter of a grocer. She went to Oxford University and then became a research chemist, retraining to become a barrister in 1954. In 1951, she married a wealthy businessman, Denis Thatcher, with whom she had two children. Thatcher became Conservative member of parliament for Finchley in north London in 1959, serving as its MP until 1992. Her first parliamentary post was junior minister for pensions in Harold Macmillan’s government. From 1964 to 1970, when Labour were in power, she served in a number of positions in Edward Heath’s shadow cabinet. Heath became prime minister in 1970 and Thatcher was appointed secretary for education. After the Conservatives were defeated in 1974, Thatcher challenged Heath for the leadership of the party and, to the surprise of many, won. On 19 January, 1976, Thatcher made a speech in Kensington Town Hall in which she made a scathing attack on the Soviet Union. “The Russians are bent on world dominance, and they are rapidly acquiring the means to become the most powerful imperial nation the world has seen.

The men in the Soviet Politburo do not have to worry about the ebb and flow of public opinion. They put guns before butter, while we put just about everything before guns.” In response, the Soviet Defence Ministry newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star) gave her the nickname “Iron Lady”. Thatcher took delight in the name, and it soon became associated with her image. Despite an economic recovery in the late 1970s, the Labour government faced public unease about the direction of the country and a damaging series of strikes during the winter of 1978–79, popularly dubbed the “Winter of Discontent”. The Conservatives attacked the Labour government’s unemployment record, using advertising with the slogan Labour Isn’t Working. A general election was called after James Callaghan’s government lost a motion of no confidence in early 1979. The Conservatives won a 44-seat majority in the House of Commons, and Margaret Thatcher became the UK’s first female Prime Minister.

If our people feel that they are part of a great nation and they are prepared to will the means to keep it great, a great nation we shall be, and shall remain. So, what can stop us from achieving this? What then stands in our way? The prospect of another winter of discontent? I suppose it might. But I prefer to believe that certain lessons have been learnt from experience, that we are coming, slowly, painfully, to an autumn of understanding. And I hope that it will be followed by a winter of common sense. If it is not, we shall not be—diverted from our course. To those waiting with bated breath for that favourite media catchphrase, the ‘U-turn’, I have only one thing to say: “You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning. (Margaret Thatcher, Conservative Party Conference, 10 October 1980)

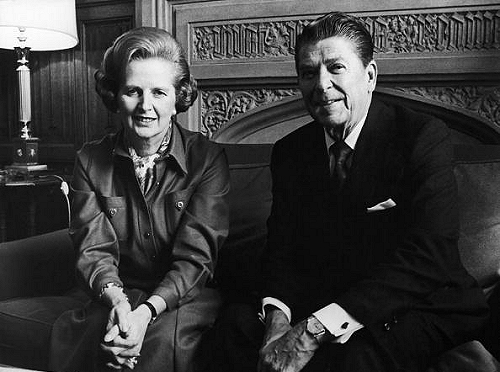

An advocate of privatisation of state-owned industries and utilities, reform of the trade unions, the lowering of taxes and reduced social expenditure across the board, Thatcher’s policies succeeded in reducing inflation, but unemployment dramatically increased. In 1982, the ruling military junta in Argentina ordered the invasion of the British Falkland Islands and South Georgia, triggering the Falklands War. The subsequent crisis was “a defining moment of Thatcher’s premiership”. She set up and chaired a small War Cabinet (formally called ODSA, Overseas and Defence committee, South Atlantic) to take charge of the conduct of the war, which by 5–6 April had authorised and dispatched a naval task force to retake the islands. Argentina surrendered on 14 June and the operation was hailed a success, notwithstanding the deaths of 255 British servicemen and 3 Falkland Islanders. Thatcher was criticised for the neglect of the Falklands’ defence that led to the war, but overall she was considered a highly talented and committed war leader. The “Falklands factor”, an economic recovery beginning early in 1982, and a bitterly divided Labour opposition contributed to Thatcher’s second election victory in 1983. In 1984, she narrowly escaped death when the IRA planted a bomb at the Conservative party conference in Brighton. In foreign affairs, Thatcher cultivated a close political and personal relationship with US president Ronald Reagan, based on a common mistrust of communism, combined with free-market economic ideology. Critics have accused Margaret Thatcher of lacking a unified set of policies for much of her rule, but a set of practices and ideals have become identified with both her and her government: these are known as Thatcherism. The Thatcher government set about privatising most of the industries run by the government, including water, electricity and the trains, selling them off relatively cheaply to new private companies. She also clamped down heavily on trade unions, passing laws designed to curb strikes, closed shops and sympathy strikes.

One of the pivotal events of her government occurred in 1984: the Miners Strike. Britain’s miners protested the government closure of “uneconomic” pits. Thatcher organised Britain around the striking miners and forced them back into work with no concessions. Other aspects of Thatcherism included selling council houses to tenants, reducing social service expenses, limits on print money and a dislike of growing European federalism. She also lowered taxes. A fierce, combative approach, a strong individualism and other aspects of her personal style became closely identified with her politics. In the 1987 general election, Thatcher won an unprecedented third term in office. But controversial policies, including the poll tax and her opposition to any closer integration with Europe, produced divisions within the Conservative Party which led to a leadership challenge. In November 1990, she agreed to resign and was succeeded as party leader and prime minister by John Major.

Not long after leaving office, Thatcher was appointed to the House of Lords, as Baroness Thatcher of Kesteven in 1992. She experienced her experiences as a world leader and a pioneering woman in the field of politics in two books, The Downing Street Years (1993) and The Path to Power (1995). In 2002, Thatcher’s book, Statecraft, was published and offered her views on international politics. Around this time, Thatcher had a series of small strokes. She suffered a great personal loss in 2003 when her husband Denis died—the couple had been married for more than 50 years. In 2005, Thatcher celebrated her eightieth birthday. A huge event was held in her honor and was attended by Queen Elizabeth, Tony Blair, and nearly 600 other friends, family members, and former colleagues. Two years later, a sculpture of the strong conservative leader was unveiled in the House of Commons. While her policies and actions are still debated by detractors and supporters alike, Thatcher has left an indelible impression on Britain and world politics.

Upon Margaret Thatcher’s passing in 2013, Meryl Streep released a statement on the Former Prime Minister: “Margaret Thatcher was a pioneer, willingly or unwillingly, for the role of women in politics. It is hard to imagine a part of our current history that has not been affected by measures she put forward in the UK at the end of the 20th century. Her hard-nosed fiscal measures took a toll on the poor and her hands-off approach to financial regulation led to great wealth for others. There is an argument that her steadfast, almost emotional loyalty to the pound sterling has helped the UK weather the storms of European monetary uncertainty. But to me she was a figure of awe for her personal strength and grit. To have come up, legitimately, through the ranks of the British political system, class bound and gender phobic as it was, in the time that she did and the way that she did, was a formidable achievement. To have won it, not because she inherited position as the daughter of a great man, or the widow of an important man, but by dint of her own striving.

To have withstood the special hatred and ridicule, unprecedented in my opinion, leveled in our time at a public figure who was not a mass murderer; and to have managed to keep her convictions attached to fervent ideals and ideas – wrongheaded or misguided as we might see them now – without corruption – I see that as evidence of some kind of greatness, worthy for the argument of history to settle. To have given women and girls around the world reason to supplant fantasies of being princesses with a different dream: the real-life option of leading their nation; this was groundbreaking and admirable. I was honored to try to imagine her late life journey, after power; but I have only a glancing understanding of what her many struggles were, and how she managed to sail through to the other side. I wish to convey my respectful condolences to her family and many friends.”

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Margaret Thatcher (April 2013)

Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World by Margaret Thatcher (2002)

Messages from Croatia by Margaret Thatcher (1998)

The Collected Speeches of Margaret Thatcher by Margaret Thatcher (1998)

The Path to Power by Margaret Thatcher (1995)

The Downing Street Years by Margaret Thatcher (1993)

The Revival of Britain by Margaret Thatcher and Alistair Cooke (1989)

Britain and Europe by Margaret Thatcher (1988)

In Defence of Freedom: Speeches on Britain’s Relations With the World by Margaret Thatcher (1987)

Margaret Thatcher in Her Own Words by Macdonald Daly and Alexander George (1987)

Let Our Children Grow Tall: Selected Speeches, 1975-77 by Margaret Thatcher (1977)