|

Simply Streep is your premiere online resource on Meryl Streep's work on film, television and in the theatre - a career that has won her acclaim to be one of the world's greatest living actresses. Created in 1999, Simply Streep has built an extensive collection over the past 25 years to discover Miss Streep's body of work through thousands of photographs, articles and video clips. Enjoy your stay and check back soon.

|

Was Karen Silkwood, a nuclear plant employee at Kerr McGee, just a trouble maker? Or did she really had sensitive information collected that would prove a contaminating of plutonium, based on security holes that her bosses knew of? Through her untimely death in 1974, which will most probably remain mysterios forever, there are no answers to this question. Her story was made into a film in 1983 in which, for the first time, Meryl portrayed a person that has really lived.

On the night of November 13, 1974, Karen Silkwood, a technician at the Kerr-McGee Cimarron River nuclear facility in Crescent, Oklahoma, was driving her white Honda to Oklahoma City. There she was to deliver a manila folder full of alleged health and safety violations at the plant to a friend, Drew Stephens, a New York Times reporter and national union representative. Seven miles out of Crescent, however, her car went off the road, skidded for a hundred yards, hit a guardrail, and plunged off the embankment. Silkwood was killed in the crash, and the manila folder was not found at the scene when Stephens arrived a few hours later. Nor has it come to light since. Although Kerr-McGee was a prominent Oklahoma employer whose integrity had never been challenged, as a part of the nuclear power industry it had many adversaries.

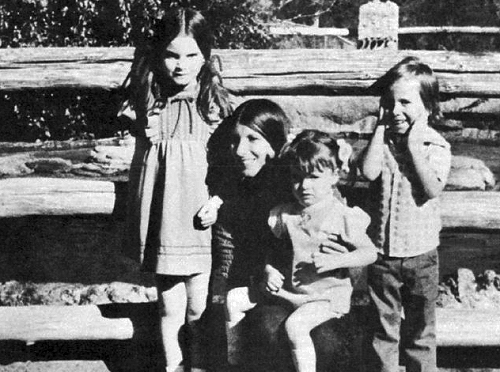

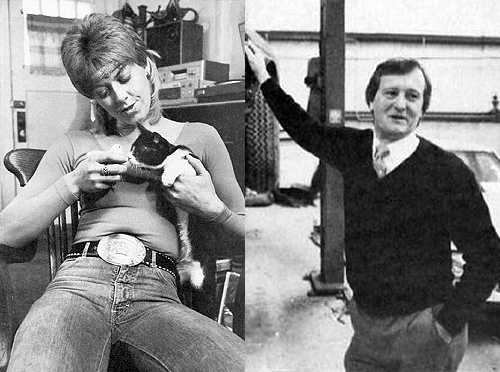

Silkwood was born in Texas, went through one year of college and had three children by a common-law husband, whom she left when she moved to Crescent, Okla., to work in Kerr-McGee’s Cimarron Plutonium Recycling Facility there. At Cimarron, she earned a reputation as someone who couldn’t be pushed around. She lived for a while with a young co-worker named Drew Stephens and was known to drink and to pop pills. At the same time, she grew increasingly troubled by the sloppy safety conditions under which she and the other Cimarron employees worked when handling dangerous, highly radioactive plutonium. One result was that she threw herself into union work and was herself “contaminated” by radioactive materials, though in ways that have never been satisfactorily explained. At the time of her death, she was alleged to have gathered evidence that would force the plant to close.

On the night of the car crash, she was driving alone to Oklahoma City to meet David Burnham, a reporter for The New York Times, to tell her story. Because of these circumstances, there are those who contend that she was murdered to keep her silent. At this point she had become almost as unpopular with many employees, who didn’t want to lose their jobs, as she was with management. There are others who are certain further that her contaminations were, in fact, not accidents but self-inflicted, in an attempt to dramatize the true gravity of conditions at the Cimarron facility, which, subsequently, was shut down. The controversy ignited by Silkwood’s death regarding the regulation of the nuclear industry was intense, with critics finally finding an example around which to focus their argument. The legacy of the Silkwood case continues to this day in the on-going debate over the safety of nuclear technology. Since then, her story has achieved worldwide fame as the subject of many books, magazine and newspaper articles, and even a major motion picture. Silkwood was a chemical technician at the Kerr-McGee’s plutonium fuels production plant in Crescent, Oklahoma, and a member of the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers’ Union. She was also an activist who was critical of plant safety.

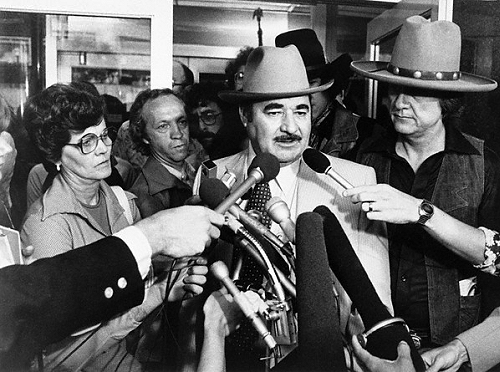

During the week prior to her death, Silkwood was reportedly gathering evidence for the Union to support her claim that Kerr-McGee was negligent in maintaining plant safety, and at the same time, was involved in a number of unexplained exposures to plutonium. The circumstances of her death have been the subject of great speculation. Speculation about foul play in Silkwood’s death has never been substantiated. However, some independent investigators at the time inferred that her vehicle had been hit from behind and forced off the road. Public suspicions led to a federal discussion into plant investigation security and safety, and a National Public Radio report about 44 to 66 pounds of misplaced plutonium. Silkwood’s story emphasized the hazards of nuclear energy and raised questions about corporate accountability and responsibility. According to the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union, the Kerr-McGee plant had manufactured faulty fuel rods, falsified product inspection records, and risked employee safety. Eventually, Kerr-McGee closed the plant. In 1986, Silkwood’s family, represented by Gerry Spence, settled an $11.5 million plutonium-contamination lawsuit against Kerr-McGee for $1.38 million.

In an interview to promote the theatrical release of “Silkwood”, Meryl Streep said: “I was attracted to the character. No matter what I think in my real life, in order to effectively play a part or make my imagination go, I have to be presented with a certain challenge and a character with problems. What I liked about Karen was that she wasn’t Joan of Arc at all. She was unsavory in some ways and yet she did some very good things. This doesn’t feel like an antinuclear movie. There are lots of those around, and I’ve stayed away from them quite purposefully because I don’t like polemics. This film is more complicated, it seems to be, and evenhanded in a funny, real-life way. The people on both sides of the question are all pretty recognizable. It has the feeling of real working life, and I think it’s about that more than anything nuclear. It was interesting to me that some of the people who were playing party in this movie, mainly Kurt, met the people they were playing. I was meeting no one; all I had were pieces of information from different pieces of information from different sources. I had details from five or six people that all described a different woman. It made me think I really ought to write my autobiography before I go, because once you’re gone, everybody has a different version of you”.

The Killing of Karen

Silkwood: The Story Behind the Kerr-McGee Plutonium Case by Richard Rashke (1981)